The manifesto that has been attributed to white supremacist Dylann Roof says that Charleston, South Carolina was chosen for the massacre of nine African Americans at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church because “it is the most historic city in my state, and at one time had the highest ratio of blacks to Whites in the country.”

Before heading to Charleston to carry out his murderous plot, Dylann Roof, who was born in Columbia – the state capital where the Confederate flag still flies defiantly on the Capitol grounds – documented his travels to other sites in South Carolina that are associated with slavery and the Confederacy, including a visit to the Museum and Library of Confederate History in Greenville, South Carolina.

The question I’ve been asking myself, as an African Americanist scholar and sixth-generation South Carolinian, is: why did Dylann Roof think he could succeed in starting a civil war by killing African Americans at a prayer service in a historic black church located in a gentrified neighborhood in Charleston?

An ‘exquisite’ city built on slave labor

Charleston is the oldest city in South Carolina, founded in 1670 by British colonists and originally called Charles Town to honor Charles II.

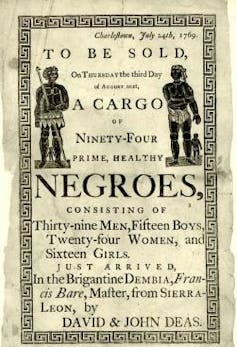

By the eve of the American Revolution, slavery profits had transformed the wealthy seaport community into a bustling colonial metropolis.

After the war, Charleston quickly emerged as one of America’s major commercial ports, with prosperous low-country planters ushering in an age of conspicuous consumption fueled by enormous profits from cash crops — namely rice, indigo, cotton and bricks — and the trafficking of enslaved African Americans who produced these commodities.

I first learned of Charleston planters’ love of ostentatious display a few years ago during a tour of the Nathaniel Russell House, a museum managed by the Historic Charleston Foundation, which is advertised as one of “Charleston’s most exquisite dwellings.”

As the docent detailed preservationists’ meticulous work in restoring the home to its 19th-century glory, she rarely mentioned the enslaved people who had worked there. So I began to ask questions about them, yearning to know more about the lives and labors of the men, women and children who made the merchant-planter’s lavish lifestyle possible. I didn’t learn much.

Dylann Roof seemed obsessed with the “high ratio” of African Americans who were forced to work for Russell and other slaveholders in the Charleston area, noting it as a motivation for him to target the city for his deadly deed.

Indeed, those ratios were as high as 9-to-1 in the low country during the antebellum period.

Although most African Americans at that time were enslaved, a small percentage was free.

Free blacks were employed in a variety of professions, including barbers, masons, cooks, seamstresses, cobblers and boat pilots, which put them in direct competition with white laborers for jobs.

Charleston’s City Council attempted to stifle competitors by setting limits on black workers’ wages and requiring them and enslaved artisans to wear a tag or badge, marking them as outsiders who were “taking over our country,” as Dylann Roof alleged.

To stanch the more recent takeover, Dylann Roof selected Emanuel AME Church as the site of the massacre.

Contested spaces

Situated on Calhoun Street about a block from Marion Square, Mother Emanuel is built on the ground where former slave and carpenter Denmark Vesey’s church once stood and with an address on a street named in honor of John C Calhoun, the pro-slavery statesman whose nullification doctrine, which affirmed a state’s right to void any federal government regulation within its jurisdiction that was not in its best interest, helped inspire secession and the Civil War.

Vesey purchased his freedom in 1800 with lottery winnings, and by 1822, he had devised a plot with members of his church and community - often during prayer meetings and Bible studies. They aimed to burn Charleston, commandeer ships in the harbor and sail to Haiti. When his plot was foiled, Vesey and 34 others were executed and his church burned.

Charleston has been contested space for centuries, ground on which African Americans have asserted their right to freedom and equality.

To help ensure that free blacks, slaves and their white allies would not conspire to overthrow slavery again, Charleston city leaders soon located the Citadel on the land that would become Marion Square, about one block north of the site of Vesey’s church.

After the Civil War, however, African Americans claimed this public space to celebrate the abolition of slavery by staging several parades.

Beginning in 1858, the Ladies’ Calhoun Monument Association, made up of influential white South Carolina women who would later support the Confederate cause, had worked to erect a statute of “one of South Carolina’s most illustrious citizens” in Marion Square. They finally succeeded in 1896 when the current 80-foot statue was installed.

This struggle over rights and place in Charleston continued into the modern era.

The city and civil rights

It was in Charleston that the Avery Institute was founded as an educational institute for African Americans in 1865, and then as a research center for African American history and culture in 1985.

It was here that the NAACP’s attorney Thurgood Marshall and Charleston attorney Harold Boulware filed Briggs v Elliot to eliminate segregation in South Carolina’s public schools in 1950.

It was here that Septima Clark was born and later started citizenship schools on Johns Island that would transform the Civil Rights movement in 1957.

It was here that Harvey Gantt, who would integrate Clemson University in 1963, participated in a sit-in at the S H Kress & Co lunch counter in 1960.

It was here that 11 black children were the first to integrate K-12 public schools in South Carolina in 1963.

When Dylann Roof chose Charleston and murdered nine African Americans, he not only took their lives and devastated their families, he attacked the institutions that have enabled African Americans to not only survive but thrive through centuries of hardships in Charleston and America.

These devoted Mother Emanuel members were not only members of a black church, but they were affiliated with black sororities and fraternities, historically black colleges and universities, public high schools, public libraries, the State House, community building institutions and barber shops.

Instead of igniting a race war that would ultimately lead to the decimation of America’s black population, Dylann Roof’s murder rampage has sparked outrage and soul-searching in Charleston and around the world.

Many turned away when African Americans were manhandled or killed when walking while black. Swimming while black. Playing while black. But when nine African Americans were murdered when praying while black, when black lives didn’t matter even during a Bible study in a historic black church in a gentrified neighborhood, some people finally started to wake up.