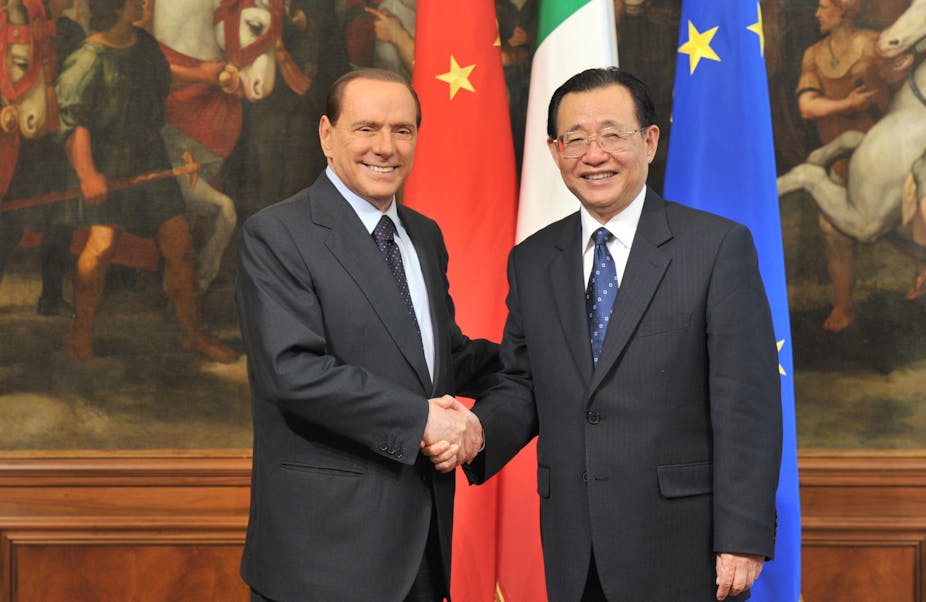

Earlier this week, reports emerged that Italian finance officials had held talks with their Chinese counterparts regarding the possibility of China making significant purchases of Italy’s public debt.

As in several other EU countries experiencing public solvency concerns, China is seen as a potential saviour from funding costs that have started to spike. The initial reaction of global sharemarkets to the news, including Australia’s, was positive.

At first glance, the match appears to be a mutually beneficial one.

China has amassed the world’s large stockpile of foreign exchange reserves at US$3.2 trillion, reflecting persistent trade surpluses and net capital inflows over the past decade.

Most of these reserves consist of US dollar-denominated assets, notably US Treasury bonds. Recent events such as the public debt ceiling debacle in the US have added weight to calls within China to diversify away from such low-yielding US dollar assets.

The EU is also China’s number one export destination and this gives it a direct stake in ensuring stability in the region.

Moreover, China became the world’s second largest economy in 2010 and is keen to demonstrate that it is an important and collegial member of the global community.

However, while it can be expected that China will continue to publicly express confidence in those EU countries facing the largest question marks – Italy, Greece, Portugal, Spain – and some modest deals may be struck, the reality is that both the ability and willingness of China to play a central role is limited.

China’s ability to purchase the sheer quantity of public debt being generated by EU countries needs to be put into context.

China’s accumulated trade surplus from January to August was US$96 billion. Meanwhile, the IMF expects general public debt in just the four EU countries listed above to increase by around US$200 billion in 2011.

In principle, China could also sell some of its existing holdings of US dollar assets and purchase Euro denominated ones. However, doing so would imply a dramatic change in its exchange rate policy and no such intention has been signalled by the Chinese authorities.

The main reason that the proceeds from previous trade surpluses have been used to purchase US dollar assets is because the Chinese authorities have desired to carefully manage fluctuations in this bilateral rate.

Halting the purchase of new US dollar assets, or selling off existing ones, would presumably see the renmimbi appreciate sharply against the US dollar.

The other reason that China has shown a fondness for purchasing US Treasuries is because they are considered low risk. The opportunity to purchase riskier and potentially higher yielding assets is not something new afforded by the EU sovereign debt crisis.

Thus, the large scale purchase of public debt from the likes of Italy would not only represent a dramatic change in its exchange rate policy, but also its risk appetite.

If there is one lesson that outsiders can draw from China’s economic reform program that began in 1979 it is that, particularly when it comes to its external linkages, changes are undertaken only gradually.

There is still an opportunity for China to play a constructive role in the unfolding EU sovereign debt crisis. For example, even modest deals struck between China and EU countries might act to soothe the nerves of other potential investors.

But such deals would only represent a temporary solution to these countries’ problems, and in the end, China alone cannot, and will not, save the EU.