As Vladimir Putin’s forces wage a brutal war against Ukraine, the Crimean Tatars living in Russian-occupied Crimea and on the Ukrainian mainland feel particularly threatened by their historic enemy’s latest invasion.

Some have vowed to defend Ukraine, a land many fled to in 2014 after Putin’s forces invaded the Crimean Peninsula and began to repress the local Crimean Tatars.

Despite the risk of 15-year jail sentences for protesting Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, the Crimean Tatar World Congress publicly came out against the invasion and said in a tweet, “Our Congress recognizes its humanitarian and moral obligation to stand in solidarity with the Ukrainians … so help them in all ways they are capable.”

From 1997 to 1998, I lived with Crimean Tatars – both in their places of Stalin-imposed exile in Uzbekistan, where many still remain, and in their ancestral Crimean homeland – while researching two books on this resilient ethnic group. I found a people who had been through centuries of genocidal persecution, but emphasized their nonviolent approach to challenging Russian brutality.

Crimea’s ancient inhabitants

The Crimean Tatars formed as a distinct ethnic group from the 11th to the 15th centuries. This ethnic formation began when nomadic Turkic horsemen, known as Kipchaks, arrived from the vast Eurasian steppe, which extends from modern-day Kazakhstan through Ukraine to Moldova. They mixed with the long-settled populations living on the Crimea’s southern shores, such as the Germanic Goths.

The final process of consolidation as an ethnic group was completed when the nomadic Mongols conquered Crimea in the 1200s and their descendants converted to Sufism, a mystical form of Islam, after intermixing with the peninsula’s original population.

The Mongol Golden Horde, a state founded by Genghis Khan’s grandson Batu Khan, subsequently ruled over Crimea and Russia for 240 years. When the Golden Horde disintegrated in the 1400s, the Tatars of the Crimea created their own Khanate – a state governed by descendants of the Genghis Khan dynasty.

The Crimean Khanate went on to rule the region extending from the Caucasus Mountains to Moldova for centuries, even after the Mongol empire in China, Russia and the Middle East collapsed.

While Crimean Tatars came to be feared by the Russians as horse-mounted raiders and enslavers of the Russian people, their bold expeditions were carried out, in part, to prevent Orthodox-Slavic settlers from encroaching on their ancestral pasture lands. For centuries following Tsar Ivan the Terrible’s conquest of the Tatars of Siberia in the 1500s, Russian settlers had began an inexorable southward advance onto the steppe lands of the Tatars, known in Russian as the Ukraina, or the frontier.

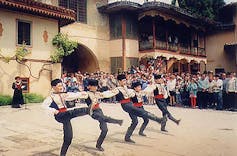

Soviet historians later tried to define the Crimean Tatars as “a mob of wild, barbarian bandits.” However, in my visits to their former capital of Bakchesaray, the Garden Palace, located in a scenic gorge in the Crimean Mountains, I found Turkish-style imperial mosques and minarets, beautiful medieval marble fountains engraved with Arabic, and a palace evocative of a lost glory.

In 1774, the Russian Empire, using vastly superior numbers and new gunpowder technology, finally crushed the Crimean Tatars’ cavalry-based army and annexed their realm nine years later.

Genocide under Stalin

The Russian conquest of their homeland almost destroyed the Crimean Tatars as a distinct ethnic group. The once-free Tatar peasants were turned into serfs by their new Russian masters, their communal lands were confiscated, and their centuries-old mosques, bazaars and graveyards were destroyed

As hundreds of thousands of Crimean Tatars abandoned their southern mountain villages and nomadic yurt encampments to flee to Ottoman Turkey, the dwindling remnants of this ancient people in Tsarist Crimea became a largely landless and repressed minority in a newly Slavic majority land.

Worse was to come under the Tsars’ heirs, the Soviets. Soviet dictator Josef Stalin decided to ethnically cleanse the peninsula’s remaining Tatar population during World War II after accusing them of being a race of Nazi collaborators.

Crimean Tatar women, children, and men, including those fighting in the ranks of the Soviet Army against Germany, were brutally deported in KGB cattle trains to the depths of Soviet Central Asia in May 1944. Approximately 1 in 3 Crimean Tatars died in an ethnic cleansing that Ukraine and several other countries later recognized as a genocide.

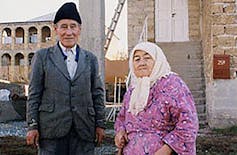

Widely dispersed from their ancestral lands in the Central Asian deserts among a hostile local population, the surviving Crimean Tatars might have disappeared as a nation under Communist programs designed to wipe out their distinct identity. But they tenaciously managed to keep their collective identity alive and fought a decadeslong, transgenerational battle to return to the romanticized “yeshil ada,” or the “green island,” of Crimea.

As Soviet rule weakened and collapsed from 1989 to 1991, approximately 250,000 Crimean Tatars, roughly half the nation, migrated back to their homeland on the shores of the distant Black Sea. By that time, the Russian administration-dominated Crimean Autonomous Republic had been made part of Ukraine.

In the late 1990s, I lived in a squatter settlement with the Shevkievs, a Crimean Tatar family who had returned to the then-Ukrainian territory of Crimea from exile in Uzbekistan. I still fondly recall eating their famous chiborek fried meat pastries, hearing ancient folk ballads of the brave, horse-mounted Tatar warriors fighting the Russians, and being welcomed with open arms by this impoverished but resilient family and people.

By this time, the Russians made up 58% of the Crimean autonomy’s population and the indigenous Tatars only 12%. Anti-Tatar sentiment among the dominant Russians was widespread. I saw crowds in the Crimea marching with placards of Stalin as an overt message of hostility toward the Tatars.

The return of the Russians

In 2014, Putin annexed the Crimea to punish Ukraine for its efforts to form closer ties with Western Europe and the U.S. For the Crimean Tatars who had rebuilt their devastated nation in democratic Ukraine, the conquest of their homeland by their historical nemesis, now ruled by an increasingly autocratic Putin, was a nightmare come true.

Among the new Russian Federation authorities’ first measures after annexing the Crimea Autonomous Republic was to ban the Crimean Tatars’ parliament, known as the Mejlis, which had given women the right to vote in 1918. They also arrested, tortured and killed Crimean Tatar activists.

Thousands of Crimean Tatars fled Russian oppression in Crimea following its 2014 annexation. Many settled in the Ukrainian capital, Kyiv, or nearby Kherson, a town Putin’s forces claimed they had captured on March 2, 2022.

One displaced Crimean Tatar, who fled the Russian invasion of Crimea in 2014 to Ukraine, declared in late February 2022, “We have nowhere left to run, so we’ll have to fight.”

[Get The Conversation’s most important politics headlines, in our Politics Weekly newsletter.]