On Sept. 1, 1914, a Cincinnati Zoological Gardens employee found the lifeless body of Martha, the world’s last living passenger pigeon, resting beneath her perch.

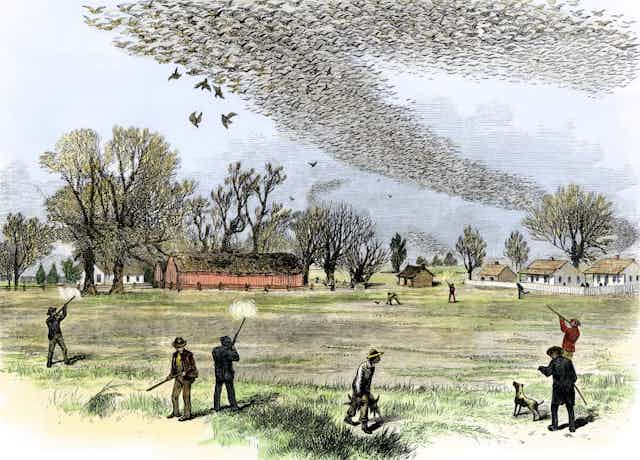

Forty years earlier, Martha’s ancestors numbered in the billions. Their flocks formed avian clouds across eastern North America, obstructing sunlight for days. The sight was so overwhelming that the American conservationist Aldo Leopold called them a “biological storm.”

By the early 1900s, only a handful of birds remained, and these were in captivity. How, in a few short decades, could one of the world’s most prodigious bird vanish from the sky?

As an archaeological scientist with a background in ecology and chemical analyses, I have always been fascinated by great extinction events and the disappearance of the passenger pigeon is one of the most notable in North America’s history. It’s exciting to look at the events that led to their demise.

Forests of food?

For decades, two theories have been used to explain the extinction of passenger pigeons. While it has long been understood that human activity caused their extinction, the exact mechanism wasn’t known.

One theory was that because the birds mostly ate a highly specialized diet of tree nuts (known as “mast”), such as acorns and beechnuts, they died off when they could no longer find enough food after the forested habitats they devoured were cut down by humans.

The other theory was that their obliteration was due mainly to humans killing staggering numbers of birds for sport and to feed growing urban populations.

The conflict between these two ideas was already evident in the early 19th century, when the almost ceaseless slaughter of passenger pigeons was well underway. After the Civil War, technological advancements, such as the telegraph and expanding rail networks, helped professional hunters, called pigeoners, to locate migrating flocks at their nesting sites and collect birds, young and old, on an industrial scale.

The great American ornithologist John James Audubon may have captured popular sentiment when he said, “… nothing but the gradual diminution of our forests can accomplish their decrease as they not infrequently quadruple their numbers yearly, and always at least double it.”

So, which was more likely: hunting or habitat destruction?

Diet clues

My colleagues and I used stable isotope analysis to study chemical markers in the bones of passenger pigeons found in archaeological deposits dating from 900-1900, in the heart of the birds’ former nesting habitat in Ontario and Québec.

An animal’s bones can tell us a lot about what ate before it died. Because bones grow and remodel slowly over the course of an animal’s lifetime, their stable isotope composition gives us information about average diet over a period of months or even years. This longer-term record of diet lets us see what a bird ate over its entire life, rather than at a single meal or in a single season.

Read more: Why giant human-sized beavers died out 10,000 years ago

Our study found that passenger pigeons could live off other foods, including farmers’ crops. This suggests that an unchecked commercial pigeon industry was likely the more important driver behind the birds’ extinction.

Prior to our research, little was known about the diversity (or lack thereof) of their diet. At the time of their decline and disappearance, no one had the technology to be able to follow and document the birds throughout their full life cycle, including cross-continental migration.

Past historical research indicated that mast was the birds’ food of choice, as they roamed up and down the great forests of eastern North America searching out patches at the peak in their masting cycle. Yet there was also scattered anecdotal evidence that the birds would at times descend on farmers’ fields of corn and wheat.

Most of the birds we sampled did eat mostly mast, but a subset had chemical compositions that suggest their diet was made up largely of crops like corn that would have been available even as their traditional sources of food grew scarcer. We also tested the subset of birds to see if they belonged to a specific age category or genetic group but found that corn-based diets occurred in both young and old birds, as well as in all genetic groups, suggesting that this dietary flexibility may have been widespread.

A new mystery?

Our analysis answered our original question, but also opened up another mystery for future study.

We performed DNA analyses to confirm the birds we were testing were, in fact, passenger pigeons. These results suggested that there may have been more genetic diversity in these birds than previous studies revealed.

Much of the previous DNA work was concentrated on birds that died not long before the species disappeared entirely, which may have meant the genetic diversity in the birds was already waning. A sample from the earlier birds in our study suggests there may have been more internal diversity during the thousands of years these flocks dominated the skies and forests of eastern North America.

Read more: Bird species are facing extinction hundreds of times faster than previously thought

This research reveals the amazing potential that archaeology and scientific techniques have for helping us understand major events of the past and how the actions of humans have shaped the world as we know it today.