At the beginning of each school year, before the students arrived, teachers from every school in the Atlanta Public Schools district were placed on school buses and taken to the old Georgia Dome.

We were not organized by alphabetical order, or even by elementary, middle or high school. Instead, all schools were organized by their test scores. The better your test results for the previous year, the closer you sat to Beverly Hall, the former superintendent of the district, who died in 2015. My experience with this event began in 2005, when I started my job as a high school English teacher in the district.

For three hours, Superintendent Hall and the principals took pictures together in front of large cardboard checks that showed how much bonus money each teacher and staff member would receive. Every school that got a check was supposedly able to demonstrate that a percentage of students demonstrated competency in one or more areas. These learning goals – or targets, as they are referred to by teachers and school leaders – were issued by district personnel and were not negotiable.

Little did I know, the festivities at the Georgia Dome were essentially an awards ceremony for what in reality was a massive and systemic cheating scandal.

Soon, teachers at the high school where I taught English began to question how it was that every single year, the elementary schools that feed directly into our high school supposedly met and exceeded their target goals in every discipline, yet by the time the students in those schools got to us, they could barely read and write.

I never once thought the answer to that question would be cheating.

Scandals keep coming

As a professor of education, I believe my experience in Atlanta is an important one to recall, especially in light of the recent graduation scandal in Washington, D.C., where hundreds of students were permitted to graduate despite missing large chunks of school, as well as a grade-fixing scandal in Prince George’s County, Maryland.

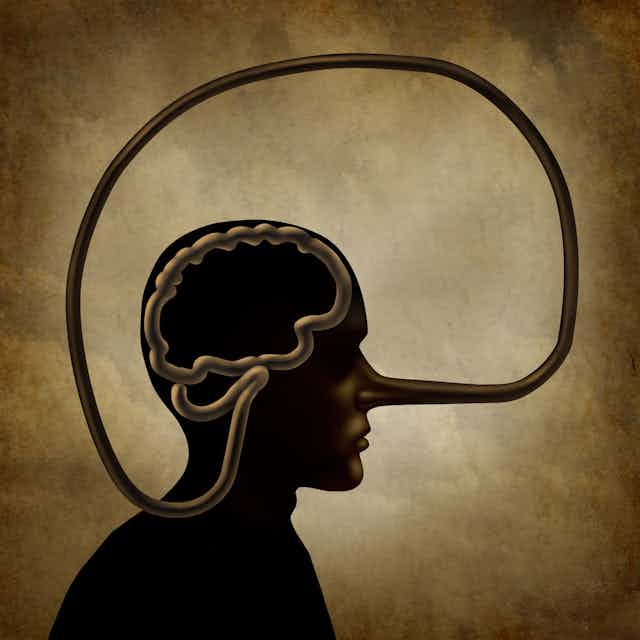

Why do these types of education scandals keep happening? There is no excuse for educational leaders to fake academic success. But in an effort to understand why certain school leaders resort to falsifying data, we need to examine what creates and sustains environments where educators feel induced to cheat, so that we can be preventative rather than reactionary.

Fear of being branded as an underperformer

A number of forces create environments where cheating seems a viable option to some. First, the anxiety around school report cards and being labeled as a deficient or underperforming school is real. No school or district wants the label. Parents don’t want to send their children to schools with poor test scores. Corporations don’t want to relocate to places where their employees can’t send their children to school.

Second, since the inception of federal initiatives such as “No Child Left Behind” and “Race to the Top,” teacher and administrative evaluations and financial compensation have been tied to test scores, even though the research states that incentive-based compensation systems have no impact on student achievement. Even more dangerous is that financial compensation and pressure can shift motivation. In my opinion, it is no coincidence that the District of Columbia Public Schools system, where the recent graduation scandal unfolded, happens to be one in which bonuses and job security are tied to annual teacher assessments.

Third, school administrators and teachers of failing schools face job insecurity and are more likely to be observed and evaluated by local, state and federal personnel. During the era of “No Child Left Behind,” between 2002 and 2015, I had between one to five different observers in the classroom at any given time, and those observations could last for the entire school year.

Notably, during my time as a schoolteacher in Atlanta, my school hired four different principals in six years. The turnover continues to this day. Teachers at the school were always under the threat of “restructuring” and having to reapply for our jobs. As soon as we were able to regroup and plan on how to reach the students in our community, our leadership was stripped away. In addition, almost every year, there were a new set of state standards or district initiatives by which we were supposed to abide.

Long-term effects

Test scores are often returned with no accompanying data that a teacher could use to revise instruction. The intense focus on data and scores also drives teachers away from the profession.

Every student impacted by grade inflation or fake attendance reports will feel the impact long after graduation.

According to a 2015 Georgia State University report, many of the students whose test scores were falsified continued to perform poorly in reading and language arts assessments. These same students, in order to graduate from high school, were later required to pass five subject tests. Some did not pass despite repeated attempts. I know this, because I personally tutored dozens of students at the high school where I worked in an effort to help them pass the test, and ultimately they did not.

Better ways to gauge academic success

During the Obama administration, the U.S. Department of Education took a small step in the right direction when it suggested a plan that states can use to reduce the amount of unnecessary testing. I would argue that more emphasis should also be placed on the use of authentic assessments – that is, testing students on what they were actually taught – at the classroom level.

School district leaders and policymakers should also seek to revamp how teachers are evaluated so that teacher evaluations are not tied to how students performed on one test on one day, but rather how much of an academic gain the students made over time.

Prospective teachers and school leaders should continue to look at the deeper meanings of teaching and learning rather than relying disproportionately on numbers. This kind of reflection will enable school leaders to shift the focus of children’s education beyond metrics and data.