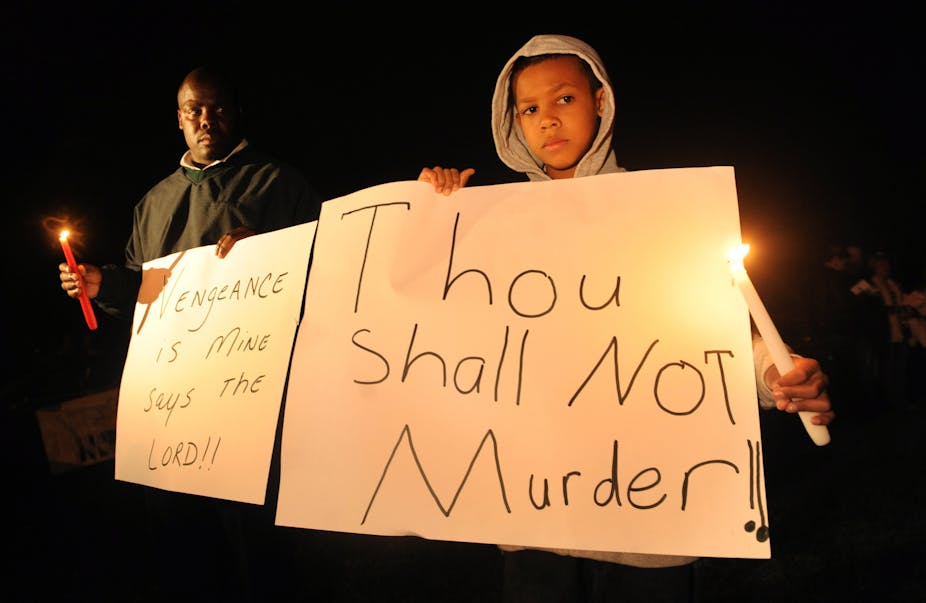

Protests in response to the extrajudicial killings of Breonna Taylor, Rayshard Brooks, George Floyd, and so many other Black Americans have raised awareness of the perennial struggle for racial justice in the US. The Black Lives Matter movement has set out several demands to achieve this aim, such as defunding the police. As I set out in my book, the struggle for racial justice also requires abolition of the death penalty, because this practice is bound up with America’s history of slavery, lynching and racial violence.

The racism of the death penalty dates to the colonial era. In 1712, the colony of New York passed a capital punishment statute that was applicable to Blacks only, in response to a revolt by enslaved people. After independence, the machinery of slavery still shaped death penalty systems across America. For example, by 1856 there were 66 crimes for which an enslaved person could be executed in Virginia, yet just one capital crime for whites. Put simply, the lives of Black people did not matter as much as the lives of whites.

Enslaved people were often subjected to more gruesome methods of execution than whites, partly because they were considered more deserving of painful deaths, and partly to send a message to other enslaved persons. For these reasons, some of the most prominent slavery abolitionists of the era, such as Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison, were outspoken against capital punishment too. They recognised that the wrong of slavery and the wrong of the death penalty were two sides of the same coin: both practices were premised on the belief that some lives were worth less than others.

Lynchings and executions

The American Civil War is often characterised as a defeat for the Confederacy and its defence of slavery, but the war did not change the mindset of white supremacists. Former owners of enslaved people and supporters of racial discrimination sought other ways to subjugate the now free Black population. They took advantage of the wording of the 13th amendment of the US constitution, passed in 1865, which outlawed slavery except “as punishment for crime”.

As Ava DuVernay’s documentary 13th explains, the criminal justice system came to be used as a replacement for the plantation, and Black Americans continued to be exposed to the death penalty at a greater rate than whites. In fact, Black Americans were at greater risk of execution than they had been during slavery. When Blacks were classed as “property” and had monetary value, slave-owners often argued for their lives to be spared. After emancipation, this was no longer the case.

Read more: US Congress could use Reconstruction-era civil rights powers to protect black lives today

Racial prejudices were central to the survival of the death penalty in the early 1900s. Colorado abolished the death penalty in 1897, and in the absence of judicially-sanctioned executions, white supremacists resorted to lynching Black people. The state legislature reintroduced capital punishment four years later not to punish lynch mobs, but to appease those who wanted to ensure that Black people could be killed.

And when campaigns against lynching led to a decline in extrajudicial executions in the 1920s and 1930s, there was a corresponding rise in the number of state-sanctioned executions, to replace lynching.

Abolition and reinstatement

The US Supreme Court abolished the death penalty in 1972, but permitted its restoration in those states that wanted it just four years later after a public backlash to its decision. As death penalty expert Evan Mandery has pointed out, criticisms of the court’s judgment were part of the more general backlash to the civil rights era, once again demonstrating the inextricable links between capital punishment and racism.

In 1987, an effort to abolish the death penalty on the grounds of its racially discriminatory application was rejected by the Supreme Court. Remarkably, the court accepted that capital punishment was being imposed in a racially discriminatory manner, but said that this was “an inevitable part of our criminal justice system” and had to be tolerated.

Intrinsic racism

The racially discriminatory application of the death penalty continues to this day, but in a slightly different manner. Today, the race of the victim – rather than the race of the defendant – plays a role in determining whether a person is sentenced to death. You are far more likely to be sentenced to death for killing a white person, than for killing a Black person. And the chances increase exponentially if you are a Black person accused of killing a white person. The most recent figures show that, since 1976, 295 Black people have been executed for the killing of a white person, whereas 21 white people have been executed for the killing of a Black person.

Recently, there have been some successful efforts in specific cases to ensure that capital punishment is not imposed in a racially discriminatory manner. In 2018, for example, the US Supreme Court overturned the death sentence of a man called Keith Tharpe when it emerged that a juror had said: “After studying the Bible, I have wondered if black people even have souls”.

However, it’s clear that racism is not a tumour that can be excised from the death penalty on a case-by-case basis, but is instead intrinsic to the system. For that reason, politicians who are serious about racial justice must recognise that the path to a more racially just society requires an end to executions.