The beginning of August means it is time for the Edinburgh International Festival, during which the Scottish capital hosts one of Europe’s premier annual arts extravaganzas over three weeks. With impeccable timing, the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art has just launched an exhibition in tribute to one of the festival’s most enduring patrons – and a lynchpin in linking art movements in Europe and the UK for the past few decades.

Richard Demarco, born in Edinburgh in 1930, has been involved in every Edinburgh festival, organising exhibitions and theatre events, since the early 1960s. He is many things – an artist himself, a curator, arts promoter and organiser – but perhaps his greatest strength is in facilitating relationships.

Over the years, he has cultivated artists, arts practitioners, curators and educators, among others. His biography reads like a catalogue of the contemporary art world, and the results of his networking have been immeasurable.

To give one example, it was Demarco who brought the celebrated Romanian sculptor Paul Neagu to the UK for the first time. Fleeing the repressive atmosphere of communist Romania, Neagu eventually naturalised in the UK and went on to teach some of the country’s most significant contemporary artists – Antony Gormley, Anish Kapoor and Rachel Whiteread.

Demarco has long seen it as his role to ensure Scotland maintained its connections with Europe, having originally been inspired by the divisions that scarred the continent following World War II. As a schoolteacher in Edinburgh after the war, he was struck by how many of his students were the result of Scottish women marrying Polish servicemen, for example. He sought to highlight his kind of shared cultural heritage and saw the arts as a way of uniting the continent.

Beuys is back in town

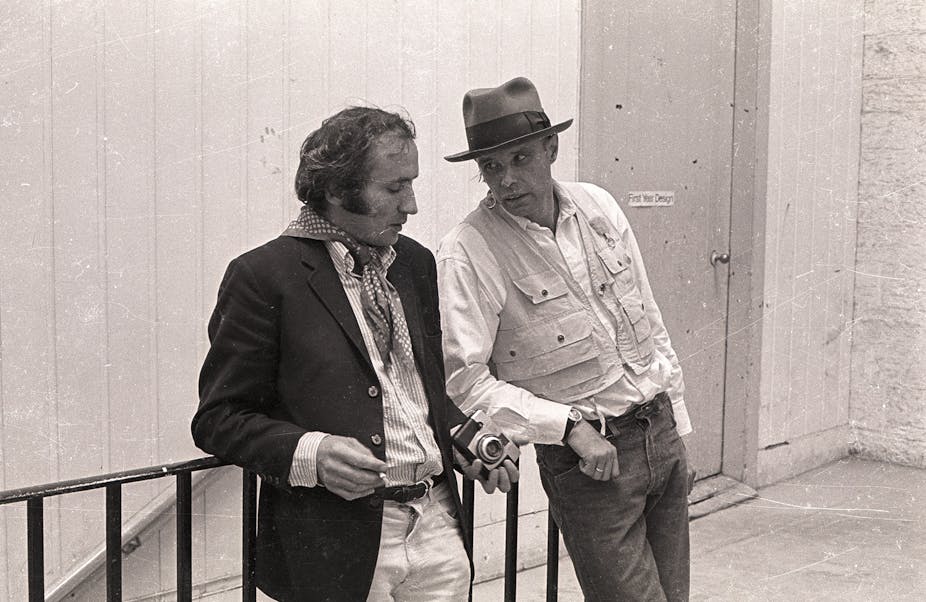

The new Edinburgh exhibition showcases the fruits from another of Demarco’s special relationships, with the German artist Joseph Beuys. Beuys is one of the most influential contemporary artists in the world. His lasting legacy in performance art has been to shift the emphasis from the objects the artist produces to the life and activity of the artist and the act of creation. The revered performance artist Marina Abramović cited seeing him in Edinburgh in 1970 as a key influence, for instance.

Beuys was there as one of 35 German artists who participated in Demarco’s Strategy: Get Arts exhibition (the title is a palinrome) for that year’s estival. Both men believed in seeing art in the everyday, and struck up a close relationship that drew Beuys back to Scotland several more times to perform until his untimely death in 1986.

Beuys was famous for his belief that anyone can be an artist, that we each have an inner creative spirit that for many remains untapped. On his way to the Düsseldorf Art Academy, where he taught, Beuys would pick up the homeless, the street sweepers and the so-called “non artists” and bring them to class. For him, their participatation in the creative process was as important as anyone else’s. When Demarco invited Beuys to Edinburgh, Beuys’ choice of performance venue was not the city’s official art spaces or theatres but the Forresthill Poorhouse, a place for the deprived and ill.

Beuys created what he called “social sculpture”: the art of the everyday, of living consciously and deliberately, considering every aspect of life as a work of art. It involves the participation of the viewer, for example in Beuys’s lectures. It is not an object but an experience.

Beuys was also fascinated by Celtic culture and saw the Scottish Highlands as a spiritual and sacred place, from which he drew much inspiration. For his original 1970 visit, he created Celtic (Kinloch Rannoch) Scottish Symphony, a five-day performance (performed for four-hours each day) in collaboration with the Danish avant garde musician Henning Christiansen that was inspired by the Highlands’ Rannoch moor. During the performance Beuys delivered a lecture to the audience while drawing a series of letters and symbols on the chalkboard, a constant feature of many of his performances, while Christiansen played his composition on the piano.

Boundary pushing

Beuys was a man of extremes: he created marathon performances in Edinburgh, such as his 12-Hour Lecture (1973), in which he speaks about things like art, creativity, socialism, democracy and freedom. In I Like America and America Likes Me (May 1974), he lived for three days in the René Block Gallery in New York City with a wild coyote. It was his attempt to access the animal primitive world of instinct, as an antidote to the anaesthetised world of capitalism.

Demarco has had a similar bent for the extreme. In 1980 he circumnavigated the British Isles on the sailing ship The Marques, not as a vacation but as a floating university. This was the final hurrah of Edinburgh Arts, Demarco’s international summer school modelled on Black Mountain College in North Carolina, US, a centre for experimental art and activity in the first half of the 20th century. Edinburgh Arts was set up as a platform for artists from around the world to meet, collaborate, and develop innovative new art projects.

This bringing together of artists is Demarco through and through. In the same way as he brought Joseph Beuys to Scotland, Demarco’s talent for building relationships has produced international connections and works of art that would not have existed otherwise. That is his enviable legacy.

Richard Demarco and Joseph Beuys: a Unique Partnership is at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art in Edinburgh until October 16. Admission free.