In November the Wellcome Collection closed their Medicine Man gallery. In a Twitter thread, they acknowledged that “the display still perpetuates a version of medical history that is based on racist, sexist and ableist theories and language.”

Medicine Man told history from a narrow, eurocentric perspective. As such, the Wellcome’s decision to rethink its gallery is not a matter of erasing history, but of deepening it.

As they rethink their collections, Wellcome and others like it must remember that decolonisation is not a metaphor, and that this move must be followed up by more concrete action.

Henry Wellcome and his collection

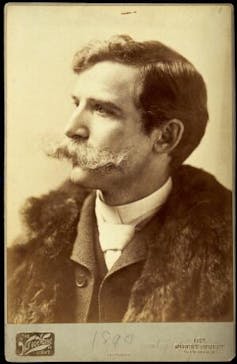

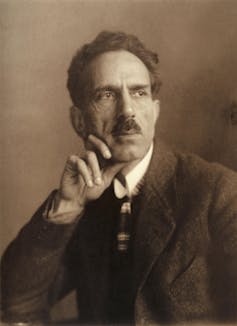

Henry Wellcome (1853-1939) was an American collector who amassed a fortune through his pharmaceutical firm.

Through a network of collecting agents, Wellcome accumulated millions of objects over the course of his career.

In 1912, collecting agent Charles Thompson wrote a letter to his colleague Paira Mall advising that he should not come home until “India is completely ransacked.”

Colonial thinking was a fundamental part of the feverish collecting in Wellcome’s company. The Medicine Man gallery is the culmination of this effort.

15 years old, it housed a selection of Wellcome’s collection, focusing on the collector, with scant context regarding how the objects were acquired.

The myth of the heroic European male collector is pervasive in personal collection museums. Collectors are often portrayed as pioneering men with a “passion for exploration”.

Museums have been slow to tackle this narrative, which omits the networks of collectors that often relied upon indigenous labour and knowledge.

This portrayal also mutes histories of violence ubiquitous in 19th century collecting.

One object in the gallery, a nail studded statue from the Democratic Republic of the Congo is dated between 1882-1920. This encompasses 22 years of the Congo Free State, a notoriously violent regime that decimated over half of the country’s population.

Displaying this object without context for its creation and acquisition allows the violence of this history to continue.

Decontextualising objects suppresses public awareness of colonial violence, facilitating historical whitewashing that allows for continued denial of accountability.

Thousands of objects in Wellcome’s collection, among millions in UK museums, were acquired in violent, colonial contexts and put on display for audiences to gawk at or walk past, unbothered. Many objects are sacred, intimate, personal. Many contain human remains.

Prior to the closing of Medicine Man, Wellcome attempted to introduce new perspectives into the gallery: alternative labels, artistic responses to objects and critical engagements led by the Visitor Experience Team.

These interventions showed an evolving attitude. Though, as the museum acknowledged, this did not change the wider narrative of the gallery.

The pivot from a Wellcome-centric narrative towards “the narratives and lived experiences of those who have been silenced” is a necessary step forward.

The state of colonial collections in Britain

Wellcome has had relative freedom within the museum world thanks to its access to private funding.

In 2020, former UK culture secretary Oliver Dowden wrote to national institutions threatening to cut funding if they took “actions motivated by activism or politics”.

As a result, alternatively funded museums such as Wellcome, Pitt Rivers Museum and the Powell-Cotton Museum have taken the lead over national ones in confronting their collections.

Though it is important to diversify perspectives in galleries, true decolonial action must stem from the active return of human remains and objects.

Looting was a tool of colonial violence, and it is only through this process that justice can begin.

The Wellcome has a history of returning human remains, fulfilling claims from Māori/Moriori and Hawaiian communities. Oxford’s Pitt Rivers Museum has set up a partnership with Maasai representatives to discuss objects of Maasai origin and London’s Horniman museum sent back 72 objects to Nigeria in November.

More institutions must follow these examples.

Those sceptical of restitution have asked – what would happen to museums if their collections were all returned? For most, this is not a realistic risk.

The British Museum has 80,000 objects on display at any one time – just 1% of their entire collection.

If any museum was emptied through returns, this would be a reflection on the historical injustices in the collection and a major success in accountability.

This question circles back to the Wellcome Collection’s original tweet - “What’s the point of museums?” It is the job of museum professionals and audiences today to grapple with this, and broaden their perspectives and imagination.

Smaller, emerging museums, such as the Museum of British Colonialism, the Migration Museum and Queer Britain, have risen to the front lines as agents for social change that help represent and respect all the histories that reflect the British community.

Museums are not neutral - the stories they tell and the objects they display are always an active and powerful choice.

A long way to go

Despite Wellcome’s positive steps, they must do more internally to ensure their dedication to addressing racism. A summer report revealed that the Wellcome perpetuated systematic racism and outlined a pattern of discrimination, harassment and microagressions faced by staff.

The report reflects broader structures of institutional racism in the heritage field.

The heritage sector has a lot of work to do before they can genuinely claim anti-racist progress.

Read more: Explainer: what is systemic racism and institutional racism?

Museums must strengthen their commitments to creating more equitable and just societies. This includes following the advice of activists in repatriating colonial collections and fostering equitable environments in their own communities.

Closing the Medicine Man gallery was a good step forward, but there is still a long way to go.