Wikipedia, the collection of 37 million articles that anyone can edit, is defined by conflict. The ability for anyone to shape this global repository of knowledge inevitably means that we are presented with fascinating, shocking, and often hilarious discussions on the talk pages of articles. See the talk pages of articles about Barack Obama, the Persian Gulf, Freddie Mercury or the best of all “lamest edit wars”.

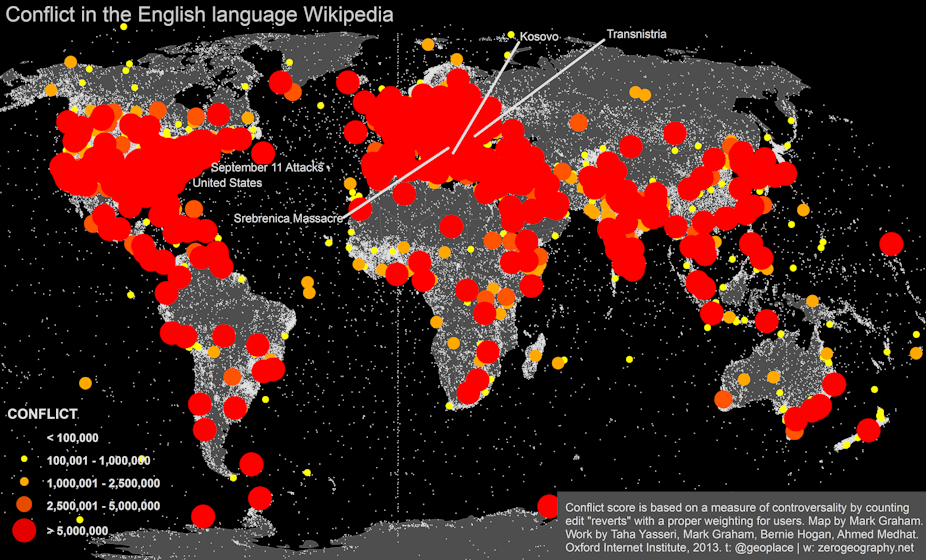

Some of my colleagues and I wanted to know whether we can model and map the controversiality of Wikipedia articles. We wanted to know whether controversy had distinct geographies? Turns out that it does. (You can find the preprint version of our paper here).

To quantify the controversiality of an article based on its editorial history, we focused on reverts, which are changes that an editor makes to undo another editor’s edits completely. We counted all of the reverts in the history of every article and gave a higher weight to editors that revert each other repeatedly.

This allowed us to get a sense of what the most controversial articles in each Wikipedia language editions are. In English, the most controversial article is George W Bush, followed by Anarchism and then Muhammed. In French, the most controversial articles are Ségolène Royal, UFOs and Jehovah’s Witnesses. Here is the full list and an interactive visualisation of Wikipedia conflicts.

The short version is that at the top of the lists in multiple languages we see articles related to religion, politics and football, something you would expect people to be arguing about. But what about the geography of these controversial articles in different languages? Where do we see the most controversial articles in different languages? At the bottom of the article is the full list of maps that we created, covering 13 language Wikipedias.

What do these maps tell us? First, we see an interesting amount of difference between the various language editions of Wikipedia. Some of the smaller Wikipedias have a high degree of self-focus in articles that are characterised by the greatest degree of conflict. For instance, we see articles with the highest amount of conflict in the Czech and Hebrew Wikipedias being about the Czech Republic and Israel respectively. Even when looking at large languages that are primarily spoken in more than one country, we are able to see that a significant amount of self-focus occurs, in for example the Arabic or Spanish maps.

The interesting exception to this rule is the Middle East. All languages in our sample apart from Hungarian, Romanian, Japanese, and Chinese actually include articles on Israel as some of those characterised by a large amount of conflict.

Also worth pointing out is that we see significant differences in the geographic topics that generate the most conflict. The articles in Japanese that generate the most conflict are not only all located in Japan and, interestingly, are all educational institutions. The Portuguese articles that generate the most conflict are similarly all located in Brazil (the world’s largest Portuguese-speaking nation), with four out of the top five conflict scores being about football teams.

Within our sample, we actually only see the English, German and French Wikipedias with a significant amount of diversity in the topics and patterns of conflict in geographic articles. This probably indicates the less significant role that specific editors and arguments play in these larger encyclopaedias.

Ultimately by visualising the geography of conflict in Wikipedia, we are able to see both topics that appear to have cross-linguistic resonance (for example the Arab-Israeli conflict), and those of more narrow interest such as the Islas Malvinas/Falkland islands article in the Spanish Wikipedia.

These maps offer a window into not just the topics that different language communities are interested in, but also the topics that seem worth fighting about.

This article first appeared on Mark Graham’s blog.