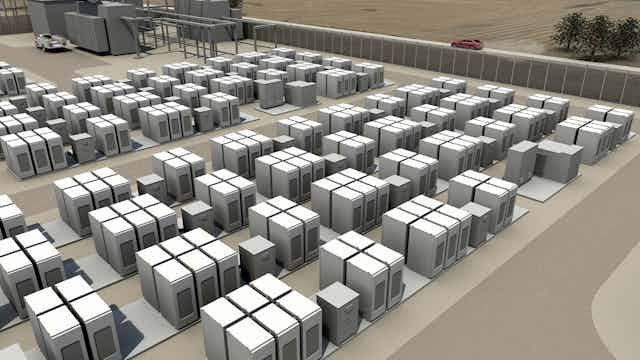

On April 30, Tesla’s Elon Musk took the stage in California to introduce the company’s Powerwall battery energy storage system, which he hopes will revolutionize the dormant market for household and utility-scale batteries.

A few days later, the Supreme Court announced that it would hear a case during its fall term that could very well determine whether Tesla’s technology gamble succeeds or fails. Justices will hear arguments on October 14 to address questions having to do with federal jurisdiction over the fast-changing electricity business.

At issue is an obscure federal policy known in the dry language of the electricity business as “Order 745,” which a lower court vacated last year.

Order 745 allowed electricity customers to be paid for reducing electricity usage from the grid – a practice known as “demand response.” It also stipulated that demand response customers would be paid the market price for not using the grid – like the power industry’s version of paying farmers not to grow corn.

Paying people not to use electricity may sound preposterous – one critique of Order 745 was that it permitted overly generous prices and lax performance standards, basically making demand response a license for electricity consumers to print money.

But research, including some of my own, has shown that demand response can make markets operate more efficiently, temper the market power held by power generating companies and reduce the risk of blackouts.

In other words, as long as the prices and rules are right, paying people to use less electricity isn’t such a crazy idea. Indeed, it’s just one way that new technologies, including rooftop solar and batteries, could make the grid cleaner and lower prices.

Smart grid on trial

The Order 745 case has already proven to be a major disruption in the US electricity market. It has thrown uncertainty into business models, market prices, and in some cases even the planning of the power grid to ensure reliability in the coming years.

The case, however, ultimately goes far beyond demand response.

The issue at hand is all about the ability of the federal government to set market rules for local power systems – that is, the portion of the grid that reaches individual homes and businesses – versus the regional grid that transports power over long distances across the US. It therefore has implications for the value of rooftop solar systems, backup generators, and even Tesla’s Powerwall battery – basically anything that would allow individual customers to supply energy to the power grid or reduce demands on an already strained infrastructure.

In fact, Order 745 could very well be the biggest energy-related Supreme Court case in decades.

The significance of this particular case is rooted in the two different and opposing directions in which technology, policy and good old consumer behavior are pushing and pulling the business of electricity.

On the one hand is a federal policy of playing a greater role in the business of managing the regional power grid, supplanting the traditional electric utility. Regional organizations now manage portions of the national grid for more than 70% of all electricity consumed in the US.

The other trend is the increasing democratization of electric power production through rooftop solar photovoltaics, small-scale energy storage devices (like Tesla’s Powerwall) and increased interest in “micro-grids” to produce, distribute and manage electricity on a localized scale. Local energy is rapidly becoming the new local food. (There has even been a buzzword – “loca-volt” – coined to capture this movement.)

The simultaneous trends of regional grid management and democratized electricity supply are now in tension with one another, not for any technological reason, but primarily for reasons of policy and economics.

The Federal Power Act, which was passed in 1935, attempts to draw a “bright line” between those elements of the electricity system that are under federal versus state jurisdiction.

The federal role is to regulate the regional transmission grid – including the power lines that transport electricity long distances and across state lines – and wholesale markets for buying and selling power. The role of the states is limited to the local grid that delivers electricity to homes and businesses and to retail sales.

Market rules like Order 745 provided a pathway for these two trends to be complementary, rather than in opposition, without a patchwork of individual state regulations.

Want solar panels on your house? Sure thing – and those solar panels could also provide power to the grid at a price, perhaps avoiding the need to build some new power plants. Or you could provide demand response by using less electricity from the grid during certain days, and more from your solar panels. Order 745 created rules to compensate people and businesses on the wholesale energy markets to lower power use, whether it was from a bank of giant batteries or highrise buildings in New York City.

Distributed energy technologies

Demand response and Order 745 are so significant because they have blurred the bright line between federal and state control over the electricity sector. This bright line is increasingly becoming an artifact of our federalist legal structure.

A regional grid operator’s primary function is to ensure the lights stay on by having enough power to match the demand. But there is no technological reason that demand response, backup generators or energy storage banks, electric vehicles, and other emerging technologies that are all part of the “smart grid” could not serve the same function for regional power grids that large power plants do today.

And there are good reasons to believe that harnessing loca-volt energy and energy efficiency will actually be cheaper than building new power plants for times when large-scale wind and solar plants aren’t available (France and some places in the US already do this, through controllable hot water heaters).

Striking down Order 745 would make the bright line ever so brighter, but it would also complicate the economic environment for one of the most innovative segments of the electricity sector.

This case, ultimately, is far more significant than getting paid for not using electricity. It’s about who gets to set the rules of the road for emerging technology in the electricity sector – the states or the federal government – and whether the US will be able to modernize its energy policy the same way that it would like to modernize its power grid. (Full disclosure: My university employer, Penn State, has been involved in a demonstration project that uses battery energy storage to balance fluctuations on the power grid in Pennsylvania and I am an advisor to the Microgrid Systems Laboratory in New Mexico.)

Before launching Tesla’s wall-mounted batteries, perhaps Mr Musk should have sat on his hands for a bit longer.

This article has been updated with more detail on the author’s involvement in microgrid projects.