Sharia councils across the UK could be facing a potentially significant rise in their workload as a result of the coronavirus pandemic, and many don’t have the resources to cope.

The predicted rise in divorce rates and reported increase in cases of domestic violence associated with lockdown measures will touch Muslim relationships just like any others. But many sharia council services are run on a voluntary basis with little funding, so it might not be possible to process all the cases on the horizon.

Sharia councils have operated in Britain since the 1980s but other religious tribunals, such as Christian ecclesiastical courts and Jewish batei din date back much further. Each has evolved to serve specific purposes within their respective faith groups. Sharia councils are used by Muslims in Britain to seek advice, manage their affairs, and settle their disputes in accordance with Islamic principles found in the Qur'an (Holy Book) and Sunnah (prophetic example).

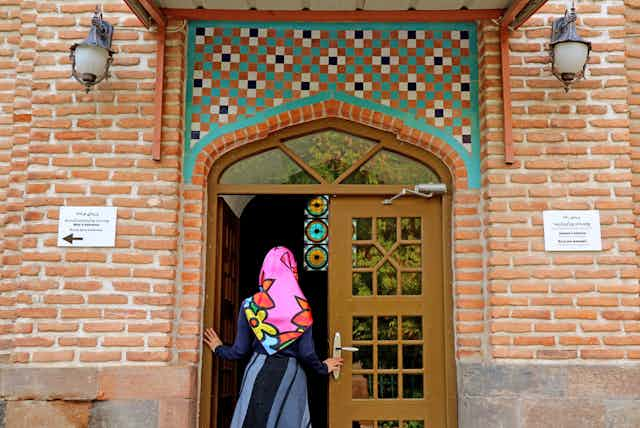

The first sharia council was established in 1982 with the objective of guiding Muslims in managing their personal affairs and settling their matrimonial problems. Over the past four decades, other sharia councils were established, often growing out of mosques and Islamic centres. Some continue to operate from there while others have moved on to running separate offices.

The number of sharia councils in Britain is unclear. One mapping exercise puts the figure at 30 while another estimates 85.

How sharia councils work

A sharia council is usually run by a panel of scholars. The administration is overseen by volunteers from the community.

Most sharia councils report that their services are open to all Muslims irrespective of their background although, in practice, ethnic diversity and different schools of thought mean that different courts interpret Islamic law in different ways.

Despite initially aiming to provide more variety in their services, sharia councils mainly work on settling marital disputes and granting Islamic divorce to Muslim women when their husband fails to pronounce a unilateral divorce or refuses to consent to the wife’s request for divorce.

Depending on the sharia council, one or more meetings are arranged to obtain testimonies and information from the person applying for a divorce, as well as with the other people involved in the case. Sometimes meetings are arranged to attempt reconciliation between the couple. The final decision is usually taken in an independent meeting between the council scholars, who then issue the Islamic divorce.

This Islamic divorce is not an alternative to civil divorce. Research shows that where a couple have had an English marriage, the sharia council usually requires or encourages them to seek a dissolution of their civil marriage as well.

Sharia councils have been widely criticised and there is documented evidence of bad practice and discrimination against women. Sometimes, men’s testimonies are privileged over women’s and there have been cases in which women have been forced into a process of reconciliation against their wishes.

However, academic research into sharia councils tells us that despite the criticisms and the many shortcomings of sharia councils, the mechanisms still provide an important service to Muslim communities. They are particularly useful for Muslim women who want to terminate marriages. Without the intervention of a council, some women might have no other way to leave their marriages.

COVID divorce

Now these councils need to contend with the fallout of the global pandemic. One of the consequences of lockdown is expected to be a rise in divorce rates. “Covid divorce”, as some have labelled it, is a trend that was first observed in China, where the rate of separations was seen to have steadily increased since the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic in Wuhan.

In the UK, there have been reports of similar trends based on testimonies from lawyers and law firms. Legal professionals have also warned about the probability of significant delays in divorce proceedings and of future case overload as divorce applications increase.

A couple of months into the national lockdown in England, one prominent sharia council, the Islamic Council of Europe (ICE), reported a more than 280% increase in its cases since April, and had to expand its team to meet the extra demand.

A number of sharia councils are likely to struggle to adapt to this sudden increase in workload, particularly as most of these institutions are known to have limited resources in terms of space, personnel and funds. In addition to the fees they charge to cover administrative expenses, most sharia councils are known to rely on community donations to cover the expenses for applicants who cannot otherwise afford their services.

Sharia councils are an important community mechanism for victims and survivors of domestic and gender-based violence, helping them put an end to abusive relationships. With emerging evidence highlighting the increase in cases of domestic violence, the need for these services is even more evident. However, with their limited resources and case overload, applicants could witness delays of several months before they see their cases resolved.

If the better-known sharia councils become overloaded with enquiries and cases, there is also the risk that people will seek help from less credible organisations with less oversight and transparency, which leaves much room for problematic practices and abuse of power. It would be very unfortunate to see Muslim women and couples more generally struggling in unsuccessful relationships with limited support and options.