On March 25 2017, two professors from Rio de Janeiro’s Federal University accompanied a group of 13 students from the School of Social Work to visit the location of their upcoming internship: Casa das Mulheres da Maré, or Maré Women’s House, a community space for women in one of the largest favela complexes in Rio de Janeiro.

The Maré neighbourhood, in the northern part of the city, is home to approximately 140,000 people who live in 16 different communities. Because it’s located along three of the city’s main expressways – the Avenida Brasil, Linha Amarela and Linha Vermelha – all international travellers drive past it, or past the wall that hides Maré from tourist eyes, on their way to the Galeão airport.

When the students gathered at their meeting point in the Parque União area, spirits were high. In neighbourhood shops and squares, locals were getting ready for a sunny Saturday and setting up for a yellow fever vaccination campaign.

Some students had mentioned that their families were concerned about them working in Maré. Armed gangs operate openly in this informal settlement, and in one seven-day period this year, a series of five conflicts left six people dead and three wounded, according to the community group Redes da Maré, which monitors public safety in the neighbourhood.

But the women felt confident. They were told that they would only enter the favela if it was safe, the walk to the Casa das Mulheres was uneventful and they were warmly greeted by the staff.

The ‘big skull’

About 90 minutes into a lively meeting, shots rang out nearby. The locals seemed calm, but WhatsApp messages pinging on mobile phones alerted Casa staff of a surprise police raid in Parque União.

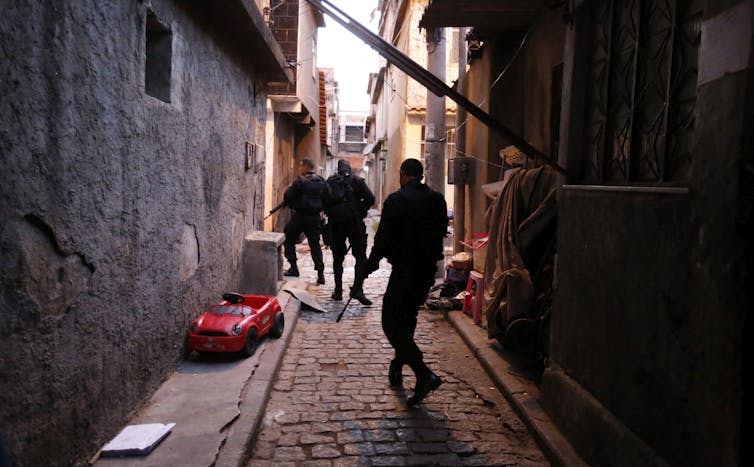

The Special Operations Batallion of the military police (known by their Portuguese acronym, BOPE), arrived at around 11am. Now gun shots were replaced by bursts of machine gun fire and explosions.

The group tried to stay calm and continue the meeting, despite frequent interruptions. When the gunfight got most intense, they took shelter under the stairs and in the back of the newly installed industrial kitchen.

Upon leaving the community centre safely at 3pm, the group passed several tanks, which locals call the caveirão (or “big skull”), and 30 heavily armed men in uniform: BOPE officers.

When they got home, they learnt that four Maré residents had died that day, not far from the Casa das Mulheres.

‘An ordinary day’

I was one of the two professors and I was distraught. But March 25 was just an ordinary day for the thousands of people who live in the conflict zones of Brazil’s second-largest city.

According to the Forum Brasileiro de Segurança Pública, a public safety research group, 4,572 people were murdered in the state of Rio de Janeiro in 2016, an increase of almost 20% over the year before. In February 2017 alone, the state registered 502 murders, which was 24.3% higher than February 2016.

Brazil’s national homicide rate is ninth in the Americas, according to a 2016 World Health Organization report, with 32.4 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants. That’s worse than Haiti (26.6), Mexico (22) and Ecuador (13.8) but better than homicide-beset Honduras (103.9), Venezuela (57.6), Colombia (43.9) and Guatemala (39.9).

But in this country of 200 million, the sheer numbers are staggering. More people were murdered in Brazil in the five-year period from 2011 to 2015 (279,567 victims) than those killed in the war in Syria (256,124 victims). Also notable is the profile of the people dying: in 2015, 54% of Brazilian homicide victims were young people between the ages of 15 and 24, and 73% were black or brown.

Police violence figures are even more stunning. Between 2009 and 2015, law enforcement killed 17,688 people. Figures from the Forum Brasileiro indicate that in 2014, 584 people died as a result of “resisting a police intervention”. In 2015, 645 out of a total 58,467 violent deaths were at the hands of police. And last year, 920 people were killed by the same forces that, in theory, are supposed to protect them.

In the Maré neighbourhood, law enforcement’s death toll last year was 17, the result of 33 police operations. This rate of 12.8 deaths per 100,000 is eight times higher than in the rest of Brazil and three times that of Rio de Janeiro state.

Safe for whom?

Already this year, Maré has already seen 12 brutal police operations similar to the one on March 25. So far, 11 people have been injured and five killed, including four residents and a police officer, according to the group Redes da Maré. These figures do not include results from yet another raid that happened while this article was in production.

Like the university professors and students who witnessed that day of violence in March, the residents of Maré and other Rio de Janeiro favelas are terrified by the city’s spike in violence.

Rio police are clearly not helping. Research shows that warlike invasions of places like Maré – primarily carried out by the military police – do not provide any positive or sustainable results. Instead, the raids create widespread fear, injure or kill innocent bystanders, and kill people: both suspects and police officers.

The day after the invasion, the old “order” is restored. Nothing changes, it only deteriorates.

Such raids leave not only a trail of blood in their wake, but also create hatred, resentment and a deep distrust of government institutions. Little by little, the image of the Rio police has become dissociated from the notions of justice and protection.

Brazil has been trying unsuccessfully to quell crime with militarised law enforcement for decades, but governments remain immune to criticism from the local population and international human rights organisations.

Of course, there is no easy solution. Definitive change in Maré would require profound socioeconomic and cultural changes across Brazil. This involves addressing the country’s structural racism, abysmal inequality and social stigma that all but justifies abusive state treatment of its poorest.

As the author Luiz Eduardo Soares has pointed out “police brutality wouldn’t exist if society didn’t allow it”. Public opinion and the media sanction these killings, otherwise the government could not keep deploying its resources against its own people. The same holds for prosecutors and justice officials who let police violence go unpunished.

Will the children of Maré get vaccinated safely this Saturday? Will the interns return to the Casa das Mulheres next weekend without fear? At this point, we can only hope.

This article was co-authored by Eliana Sousa Silva, PhD, executive director of the community organisation Redes da Maré.