Evidence of the first people to settle in Australia can be found in the Willandra Lakes World Heritage Area, in western New South Wales, informally referred to as Australia’s Rift Valley. Hundreds of archaeological sites dating back to the last Ice Age are found across the landscape.

The remarkable discoveries from the Willandra have revealed a story central to our understanding of the colonisation of this continent by the First Australians. They also add to our understanding of the complexities behind the initial dispersal of our species Homo sapiens across the globe.

More than 100 ancient human remains from the fossil lakes have been discovered, beginning in 1968 with Mungo Woman, the world’s earliest example of ritual cremation.

In the past week, leading up to the 40th anniversary of the discovery of the first Australian Mungo Man, we have seen news reports highlighting retired geologist Professor Jim Bowler’s “fight” to have the 42,000 year old fossil remains returned from current storage at the Australian National University (ANU).

It is not clear who the fight is with as agreement already exists between ANU scientists and Traditional Owners that they should be returned some time in the near future. In many ways Professor Bowler’s fight is reminiscent of Don Quixote’s famous battles with the windmills of Spain. The fight is an imaginary one.

The keeping place

But there is a problem with getting acceptance on why it is so important to build a culturally respectable solution to the return – one that further encourages reconciliation between Traditional Owner values and the continuation of research.

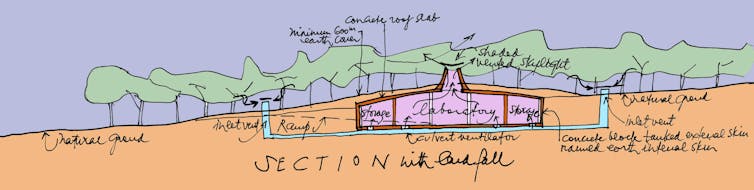

For many years there have been careful plans to build a keeping place for these extraordinary ancient remains. This would be a sub-terrain facility that returns the ancient remains to the earth, but still allows access to bonafide research.

The keeping place concept has been at the centre of discussions on how to best manage the remains of the First Australians for well over a decade. It has attracted the attention of some of our nation’s most inspiring architects, including Gregory Burgess and Glenn Murcutt. But sadly the concept has been frustrated by governments of both persuasions.

This is the first real stumbling block in terms of the repatriation.

Limited access to remains

The second stumbling block has not been a real issue since the 1980s, when archaeologists actively resisted repatriation in Australia. But research seems to be identified in the recent debate as a possible obstacle to the return.

In a letter to the editor in The Australian last month, by Professor Jim Bowler, his statement that “after 40 years in the service of science, Mungo Man’s homecoming will release new voices from the grave” requires clarification.

His claims that “research has long since been exhausted” and “the time has come now for the bones to come back to country” are ones that seem to infer that scientists are resisting the return.

For most of the time that the collection sat at the ANU the fossil remains were not accessible to scientists other than the late Alan Thorne.

Dr Thorne was a giant in Australian palaeoanthropology – he excavated and studied the vast majority of the fossil remains that have ever been found in Australia. His work at Lake Mungo and Victoria’s Kow Swamp is known across the globe.

But these fossils were accessible to very few, descriptions were never published of key individuals, and indeed very few papers were produced. Anyone in the field of biological anthropology knew that the collection was carefully guarded and not generally in the service of science.

There were many reasons for this. Dr Thorne was very sensitive to the fact that he did not want to cause distress to the Willandra Elders, and he was also very protective of his research.

Working with the Elders

Biological anthropology, the science that studies human variation and evolution has many, many sub-fields – too many for one scientist to try to cover. Over the years I have introduced new colleagues to the Elders and together we have explained what these new studies potentially can reveal.

The Elders now for more than a decade have patiently listened to requests. For the past ten years my colleagues and I have been given the privilege to study the extraordinary remains from the Willandra Lakes World Heritage Area.

We have published information on origins of the First Australians how this sits in context with modern human origin across the globe, micro evolutionary change, sex, pathology and even the use of teeth as tools for making nets. We have received funding to attempt to recover ancient DNA using next generation sequencing, computed tomography (CT) scanning, and micro CT scanning to investigate pathology.

The research is always undertaken with Elders present, and when there has been media, such as the wonderful First Footprints documentary by the ABC, we have stood side by side with the Elders presenting the stories together.

A delicate balance

Each time we ask to do more research I worry that perhaps we have asked too much, and worry that we may have caused offence, but the interest from the Elders seems to have always remained. In the past few years the Elders have informed me: “Better hurry up, we are bringing them back soon.” The plans for the return of the remains to the Willandra have progressed, and we have accepted this.

Last year when I first heard of Professor Bowler’s plans to fast-track the repatriation I contacted him to mention that we had received further funding from the Australian Research Council (ARC) to progress the ancient DNA work.

Ancient DNA may still reside in the fossils and we don’t know what secrets the bones still hide.

This exchange was the first time I heard there would be no more research on the fossil remains while they were held at the ANU. “The horse has bolted,” Professor Bowler declared.

The ANU holds the technological capacity to draw out more information from the ancient remains prior to their return. This includes more reliable estimates on ages of the ancient people and micro CT scanning facilities to hopefully unravel the extraordinary pathological condition of the fossil known by science as WLH 50.

This incredibly robust fossil has been a focus of much scientific debate. Does this 20,000-year-old man provides evidence of later migrations into Australia from a different population, or could he have suffered from a form of ancient anaemia? We do not yet have any answers.

There is still time to learn more before the return, and one day I hope there will be Aboriginal biological anthropologists who can lead the same path of discovery of which we have been so fortunate to be a part.

Since publication this piece has been amended to remove reference to Professor Bowler as an Emeritus Professor, at his request.