Welcome to the first essay in our series on how the Australian landscape has been described in literature. We start with an internationally recognised D. H. Lawrence scholar, Christopher Pollnitz, writing about Lawrence’s 1923 novel, Kangaroo.

The indifference — the fern-dark indifference of this remote golden Australia. Not to care — from the bottom of one’s soul, not to care. Overpowered in the twilight of fern-odour. Just to keep enough grip to run the machinery of the day: and beyond that, to let yourself drift, not to think or strain or make any effort to consciousness whatsoever.

D. H. Lawrence, from Kangaroo (1923)

As D. H. Lawrence circled the globe, he made a point of going to the barber’s – this despite his trademark beard – and of buying a pot of honey. The barber in Thirroul, he noted, was an unusually intelligent young man, au fait with political trends in the 1920s and able to put an English visitor in touch with social life in the NSW South Coast village. The honey he would taste to commune with the vegetative spirit of place.

Lawrence tried defining the “spirit of place” in his Studies in Classic American Literature. It was, he contended, a “great reality,” albeit one that operated via emanations or effluences. It produced a race or a nation as much as it was produced by a people seeking to establish themselves in terms of their homeland. Tied up with Lawrence’s thinking about spirit of the place was a melange of ideas about indigenousness, race theory, and occult universal wisdom. Such ideas all speak at once, and are questioned, discarded, and reformulated, in Lawrence’s Kangaroo, a novel he wrote in ten weeks – all but the last chapter – while living under the Illawarra Escarpment in Thirroul.

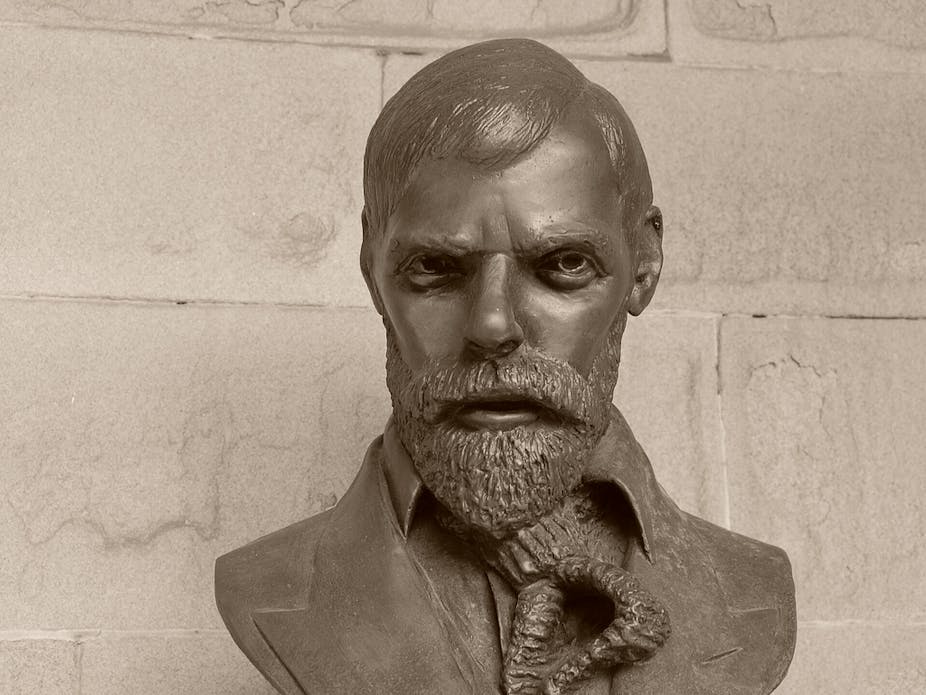

He sailed into Circular Quay and disembarked on 27 May 1922, close to the spot where his medallion used to be on the Writers’ Walk. It is unclear when the medallion was deleted from the Walk, but its disappearance probably had more to do with the perceived sexual politics of Lawrence’s other fiction than with any concern about the writing of place in Kangaroo.

A Scottish writer and influential academic in Australia, J.I.M. Stewart, wrote in early praise of the novel’s descriptions of nature. Poet Judith Wright took it further; comparing Kangaroo with Patrick White’s Voss, Wright commended Lawrence’s insight into what she too thought was missing from the psychology of twentieth-century white-colonial Australians – any appreciation of how the continent itself, its flora and fauna, might provide the platform for a grounded sense of national identity.

Strange, then, that in the twenty-first century some have found it desirable to expunge from Australian literary history a writer who, as well as setting a novel on the east coast, has had an impact on the finest Australian-born poets and novelists. Strange and futile. Attempts to censor Lawrence out of consciousness are counter-productive, as the Lady Chatterley trial proved fifty years ago. A better plan of action is to engage with his ideas.

Kangaroo includes a succession of quirky bush vignettes, starting with one in the Perth Hills. Lawrence stayed there a fortnight, and met and talked with Mollie Skinner. He later co-wrote The Boy in the Bush with Skinner, or rather rewrote her first draft. In the first chapter of Kangaroo the Lawrentian character, Richard Lovatt Somers, recalls night-walking in the West Australian bush, and romanticises –that’s to say, lets himself be frightened by – the “huge electric moon” and the bush “hoarily waiting.” He senses the bush “might have reached a long black arm and gripped him.” Fortunately, as this colonial fear fantasy never eventuates, Somers’s feeling for the landscape grows progressively more nuanced.

Somers-Lawrence also observes tree trunks charred by bush fires and a burn-off as he returns from his night-walk, the red sparks glowing under the southern stars.

Once Somers reaches Thirroul, renamed Mullumbimby in Kangaroo, the novel develops a plot and complication. Will Somers let himself be recruited to the Diggers, a right-wing paramilitary organisation?

By now a reader, curious whether the “long black arm” of Chapter I was an over-extended Aboriginal limb, will be noticing that indigenous characters are conspicuous by their absence, while white characters are indifferent to any activism not directly reflecting northern-hemisphere political contests and wars.

In Chapter X, after a “ferocious battle” with his wife Harriett, Somers climbs the Escarpment and looks back down over a dark mass of “tree-ferns and bunchy cabbage-palms and mosses like bushes” to the narrow coastal strip. A relic of the coal age, the vegetation tempts Somers to enter into a “saurian torpor,” to succumb to “the old, old influence of the fern-world,” under which one “breathes the fern-seed and drifts back, becomes darkly half-vegetable, devoid of pre-occupations.” What would now be called the New Age rhetoric of this passage conflates geological periods with the millennia in which human societies began developing cosmogonic myths. The dodgy subtext might be that, to attune itself to the Escarpment’s spirit of place, colonial Australia needs to dumb down its Western consciousness – dumb it down until it can vibrate in indigenous accord with the spirit of place.

While the botanically trained Lawrence knew perfectly well that ferns reproduce from spores, he also knew, from J.G. Frazer’s The Golden Bough, that he who takes the mythical fern-seed between his lips has the power to become invisible and see into what is hidden in the earth. Giving Lawrence the benefit of the doubt, another subtext is that European Australians need to develop new ways of apprehending an ancient environment.

As for tree-ferns being survivors of the dinosaur age, Lawrence might have also noticed that the Escarpment was, and remains, a lively skink habitat.

Lawrence’s knowledge of the initiation rituals which showed Aranda men their spiritual identities in the Central Australian desert came from another of Frazer’s anthropological works, Totemism and Exogamy. The climax of Kangaroo, a blood-letting in the streets of Sydney, is a hideous parody of such rituals. This clash between Diggers and unionists brings neither victors nor victims a jot closer to belonging to the continent.

Disillusioned by the riot, Somers and Harriet make a last springtime excursion, to the Loddon Falls. The Loddon rises above the Escarpment and flows inland, disappearing underground into a “gruesome dark cup in the bush.” That alien spirit of place to which European consciousness must learn to accommodate is still being registered. But the passage joins others, in Twilight in Italy and “Flowery Tuscany,” as an ecstatic hymn to floral abundance and variety. It’s great fun for local readers, who have to guess at misnamed flowers (the “bottle-brushes” are banksias) or unnamed flowers from their descriptions. My guess is that the “beautiful blue flowers, with gold grains, three petalled … and blue, blue with a touch of Australian darkness,” are Commelina – common name, scurvy grass, probably because it is useless for fodder.

Admittedly, Lawrence described the stems of this blue-flowering creeper as “thin stalks like hairs almost,” making it sound more like the Austral bluebell or even Dianella. Possibly he was conflating more than one flower in memory, for the whole wildflower paean in the last chapter was written from recollection, after he arrived in New Mexico.

There is nothing utilitarian, then, about the descriptions of the Australian bush in Kangaroo. Or perhaps there is, marginally. At least one council has begun to use Commelina as an ornamental ground cover, so helping distinguish it in the public mind from bush-suffocating infestations of the South American Tradescantia. What can be claimed for Lawrence’s brilliant botanical shorthand – “blue flowers … gold grains, three petalled” – is that even now he has the power make us look, and look again, at the environment. For that, he is worth a medal.

Christopher Pollnitz is preparing a critical edition of Lawrence’s Poems and is a member of a bush care group.