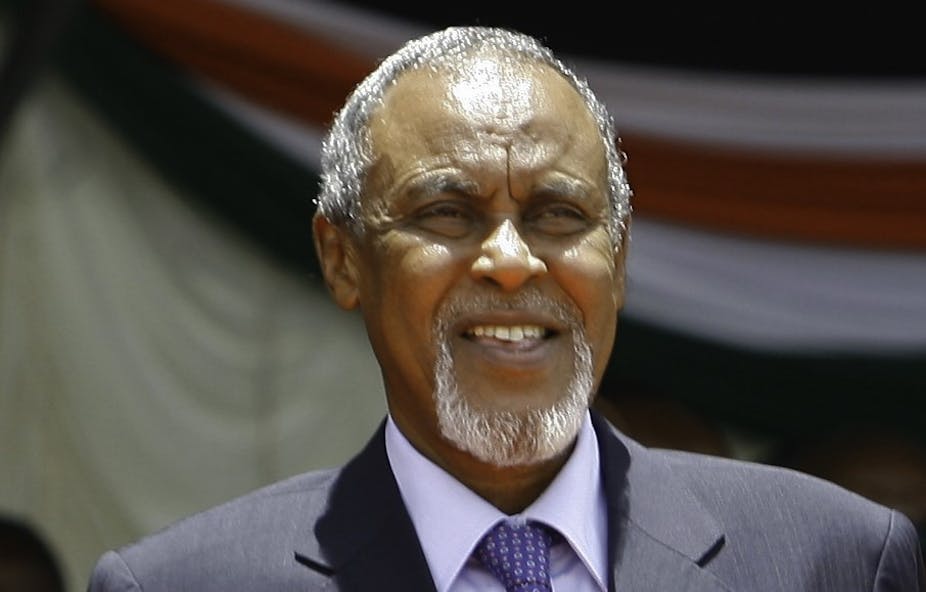

One of Kenya’s best known government administrators, Mohamed Yusuf Haji, died recently aged 88, still actively engaged in public service as both senator and chairman of a constitution revision team.

Born in Garissa in 1940, Haji was a beneficiary of the pre-independence colonial initiative to identify young talents to fill the shoes of departing British colonial administrators. He joined the administrative service as a District Officer in 1960.

In that year, Britain called the first Lancaster House Conference to determine Kenya’s future. It decreed that ‘natives’ would rule. Officials then intensified recruitment of potential African administrators and bureaucrats.

Simeon Nyachae, another long serving administrator wrote in his autobiography that new recruits were trained to take over Kenya’s administration at independence.

Officers in the provincial administration were expected to be very loyal to the state and had to do as ordered, without questions. Haji learned this lesson well, remaining loyal to the interests of the Kenyan government throughout his career in public service.

Haji, the most prominent provincial administrator from the Somali community, later became a politician in 1998. He remained a people’s representative until his death.

Two public images

Veteran Nairobi journalist John Kamau wrote recently that Haji had two public images; the administrator who threw his weight around on one hand, and the humble peacemaker on the other.

As an administrator, Haji attracted negative attention. He once had a man imprisoned for not giving him a lift and was also known to enforce draconian rules.

As a provincial commissioner in Kenya’s Rift Valley province, Haji became synonymous with former president Daniel arap Moi’s 1980s excesses. He was accused of fanning ethnic clashes in 1989, 1992, and 1997. And two human rights investigative commissions – the Akiwumi Commission of Inquiry and the Truth, Justice, & Reconciliation Commission – called him out for his alleged role in these ethnic clashes. He was accused of playing a part in the mass evictions of certain ethnic groups from Kenya’s Rift Valley province. Ethnic clashes were common during the Moi regime. Moi used them to score political points and to undermine his critics. But Haji denied any involvement.

Read more: Simeon Nyachae: the larger-than-life civil servant who made his mark on Kenya

The peacemaker

His 1998 nomination to Parliament put him on the path to widespread respect as a wise political operative and peacemaker. He remained steadfast to the ruling party, the Kenya African National Union (KANU), resisting the 2002 National Rainbow Coalition wave that ousted KANU from power after a 39-year run, 24 of which were under Moi’s watch.

In 2002 he won the Ijara Constituency seat on a KANU ticket and was reelected in 2007. Notably, he served as the minister of defence from 2008 to 2013 during Kibaki’s second term in office. It was during his tenure that Kenya Defence Forces troops were deployed to Somalia to fight the Al-Shabaab.

His handling of troubled Somalia during President Mwai Kibaki’s second administration (2007-2013) made him a peace maker.

As part of his regional peace efforts, while serving as minister of defence, Haji helped to establish Somalia’s Transition Federal Government. He also supported the training of Somali security forces to fight terrorists.

Notably in 2011, Haji led a Kenyan delegation to meet with officials of Somalia’s Transitional Federal Government. They discussed how to manage the Al-Shabaab menace. He and Somalia’s Minister of Defence Hussein Arab Isse signed an agreement to collaborate against the insurgent group. Kenyan troops were then deployed to fight the terror group.

Eventually, he was part of the team that made the ultimate decision to pursue the Al-Shabaab terrorists into Somalia, and witnessed Kenyan soldiers being ‘re-hatted’ into the African Union Mission in Somalia.

From 2013, he served as the Senator for Garissa County in Northern Kenya, and in the final years of his life he was appointed the chairperson of Kenya’s Building Bridges Initiative Task force. Unfortunately, he did not live to see it fully implemented.

Read more: Kenyatta and Odinga's pact has led to a new elite alliance. Why it won't last

The initiative to amend the constitution arose out of a March 2018 pact between Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta and Former Prime Minister Raila Odinga. They came together after a contentious election in 2017 that divided the country between the supporters of the two candidates.

Haji, the man

From my experience, Haji was soft spoken, straight to the point, and open to ideas. He was a man of his time, representing conflicting parties, and able to adjust to prevailing realities. In his youth, he rose above secessionist parochialism to join the provincial administration despite the fact that his father, the elder Yusuf Haji, led a secessionist political party – the Northern Frontier Democratic Party.

While Haji – a Kenyan Somali – committed to serving the Kenyan state early in life, his father, Yusuf, was pushing for the secession of Kenya’s Northern Frontier District to Somalia. The secessionist movement, which began in the 1960s, eventually failed and officials in the provincial administration grew in power.

While in the provincial administration, he adjusted to the governing tradition of total obedience to political superiors. He did what was expected of him and he ended up being indicted for abusing human rights, mainly at the behest of his superiors.

And when he joined politics as a ruling party adherent, he quickly adjusted to the reality of multi-party politics. He refused to join Raila Odinga’s 2002 rebellion within KANU, won the Ijara seat under the KANU umbrella, and remained loyal to party leader Uhuru Kenyatta, who went on to become Kenya’s fourth and current president.

Haji became a sober elder, paying attention to volatility in the region. His efforts to ensure stability in Somalia gave him the reputation of a peacemaker. And by the time of his death, he had witnessed four political transitions from colonialism to Uhuru Kenyatta. He, in many ways, embodied the colonial and post-colonial Kenyan experience.