Articles on Astronomy

Displaying 1 - 20 of 802 articles

Research on one exoplanet that’s rapidly losing its atmosphere is hinting to scientists why exoplanets tend to look a certain way.

A new study shines light on the link between the Milky Way and the ancient Egyptian sky goddess Nut

It’s not easy to collect rocks on a budget when the rocks are 140 million miles away.

MeerKAT has made remarkable contributions to South African and international science.

When astronomers focused on the galaxy NGC 4383, they didn’t expect the data to be so spectacular. This is the first detailed map of gas flowing from this galaxy as stars burst within.

If you look carefully at the night sky, you may spot this fuzzy visitor with the naked eye – but binoculars will help.

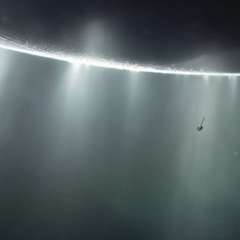

Saturn’s moon Enceladus has geysers shooting tiny grains of ice into space. These grains could hold traces of life − but researchers need the right tools to tell.

When scientists observed planets revolved around the Sun, they posited we were now like other planets. And if other planets were like Earth, then they most likely also had inhabitants.

Where specialized algorithms fail to classify star-borne pulses, human volunteers with just a little training can step in.

A type of eclipse is crucial for measuring what’s in the atmospheres of planets orbiting distant stars.

Now out in space for more than two years, the James Webb Space Telescope is a stunningly sophisticated instrument.

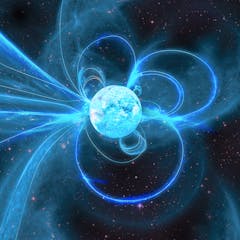

Astronomers caught the bizarre ‘awakening’ of an incredibly rare magnetic star.

Textbooks often show Earth’s orbit around the Sun as an almost egg-shaped ellipse. The real story is very different.

To protect their kings, ancient Mesopotamians discovered how to predict eclipses, which were associated with the deaths of rulers. This eventually led to the birth of astronomy.

Eclipses have long fascinated and intrigued people, and anticipation of the total solar eclipse on April 8 is no exception. The beauty, history, mythology and science of eclipses justify the hype.

A total solar eclipse is a beautiful phenomenon worth seeing, but worth seeing safely.

Since an eclipse only lasts a few minutes, you need more than just a handful of scientists running around collecting data on bird activity. That’s where a new app comes in.

The sky is becoming more cluttered with satellites and space junk. This is affecting astronomical study, but will only have a minor effect — if any — on the viewing of the solar eclipse.

The skies and the gods were inseparable in Maya culture. Astronomers kept careful track of events like eclipses in order to perform the renewal ceremonies to continue the world’s cycles of rebirth.

Some ancient texts record what were likely dying stars, faintly visible from Earth. If close enough, these events can disturb telescopes and even damage the ozone layer.