There can be little doubt that this year’s elections in Germany and France may determine the future of the European Union.

For nearly a decade now, the EU has been facing unprecedented challenges, from the euro crisis and the influx of migrants to Brexit and the rise of nationalism. On their own, any one of these crises could threaten the cohesion of the union; together they represent an existential threat.

But the tide could yet turn. Depending on the outcomes of the French and German elections, 2017 could actually be the start a more integrated and unified Europe.

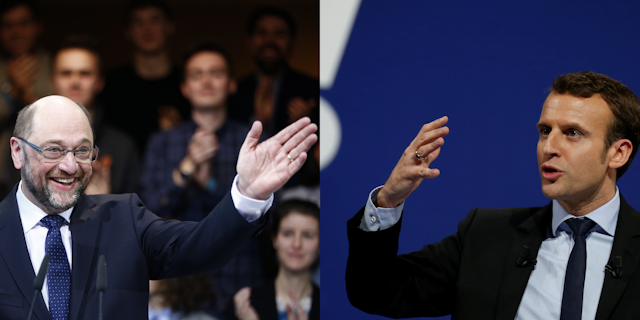

The rise of Emmanuel Macron

France is facing one of its most fascinating election in recent history. Former prime minister François Fillon, a traditional conservative, looked likely to win power. But an embarrassing corruption scandal involving the employment of his wife Penelope has significantly dented his chances.

The Socialist candidate, Benoît Hamon, is highly unlikely to make it far. Having won the socialist primary on a very left-wing platform, it will be difficult for him to reach beyond his core group of supporters.

Leading the polls is Marine Le Pen, the leader of the far-right Front National, who is running on a populist, eurosceptic, anti-immigrant platform. Le Pen is projected to win the first round of voting on April 23, but she is most likely to be knocked out in the second round, where 50% of voters are required to win.

The man who defeats Le Pen in the May 7 second round may not come from either of France’s main parties. Emmanuel Macron is now one of the favourites to win the elections.

Macron’s political success has come incredibly fast. An unknown three years ago, he is now on track of possibly becoming the youngest president of the Fifth Republic, at age 39.

As a minister, Macron was vocally pro-business, in conflict with the classical tenets of the French left: he defended Uber, the opening of shops on Sunday and the reduction of the costs to terminate labour contracts. He became very popular with the French public while finding himself at loggerheads with many figures of the ruling Socialist party.

In August 2016 he quit the government and launched a presidential bid as an independent. Half a year later, he has transformed his initial political start-up into a political movement, En Marche (Forward), with political rallies that attract thousands.

His strength comes from the match between his discourse and French voters’ desire for change. His left-liberal political position would not be unusual in many Northern European countries, but in France it is a novelty. Nearly 30 years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, the French left has not adapted to economic modernity. Facing the competition of a strong Communist Party in postwar France, the Socialist Party maintained a traditionally anti-capitalist position. This ideological position has often been disconnected from social-liberal policies adopted once in government.

By seizing on these contradictions and crossing the left-right divide, Macron has thrived. His novel political platform is characterised by an economic liberalism blended with concern for social justice and political and cultural liberalism.

Young, charismatic and intellectual, Macron has attracted people from both the left and the right, and drawn a lot of newcomers to politics. At the same time, political space has opened for him. Both Fillon and Hamon are hard-line candidates, leaving an spot in the centre for Macron.

A Macron victory would have important consequences for the EU. Unlike most French politicians, who are either shy integrationists or vocal eurosceptics, he is strongly pro-EU; his supporters cheer for Europe in political meetings.

In January, he wrote in the Financial Times that it was time for Europeans to become sovereign. This stance could end French opposition to deeper political integration.

The election of Marine Le Pen would lead to the unravelling of the EU, but if France chooses Macron, the union will get a significant boost from one of its core members.

Germany: a new hope for the SPD

The other key country in holding the EU together is of course Germany, which goes to the polls on September 24. Angela Merkel, of the Christian Democratic Union, is running for her fourth term as chancellor.

Hoping to dislodge Merkel from the Bundestag is Martin Schulz of the Social Democratic Party (SPD). In January, the none-too-popular Sigmar Gabriel made way for Schulz to become the part’s lead candidate.

Schulz is a rarity in European politics, having made his career in the EU before vying for a top national position. A member of the European Parliament since 1994, Schulz was its president from 2012 to January 2017.

There, he helped stage a political coup that dramatically shifted the balance of EU institutions, transferring power from the Head of States (Council) to the Parliament, and through it to European voters.

In 2010, the Party of European Socialists decided to name a leading candidate to become the president of the European Commission in case of victory at the 2014 European elections, and chose Schulz. But the European elections in May 2014 did not deliver a clear majority.

Schulz could have tried to form a majority on the left, but he instead supported a cross-bench motion from the European Parliament stating that conservative candidate Jean-Claude Juncker was the winner of the election and that he had to be nominated.

Schulz understood the political game he was facing. The Council wanted to keep nominating the president, and the lack of a clear majority gave it the opportunity to propose another candidate. Schulz’s decision to withdraw gave the Parliament the upper hand instead.

At the time, Merkel seemed to indicate that she would not support Juncker. She faced a storm of criticism in the German media and was accused of betraying the democratic promise of the election. Soon after, she caved and endorsed Juncker.

Martin Schulz’s key role in this manoeuvre indicates that as chancellor he would probably leverage Germany’s power to further EU integration. It would mark a substantial change compared to Merkel, whose approach has been to take as few steps as necessary and to protect German finances before all.

Deeper integration

Could Macron or Schulz have an impact on European integration? Most likely.

Many factors in the current context are pushing in that direction. Politically, the lack of accountability and transparency of decisions at the European level is feeding a rise of nationalism; that threatens many European governments.

Geopolitically, we are witnessing both a resurgence of Russian military threat and a withdrawal and unpredictability of the US ally under Trump. Economically, crises are clearly calling for better coordination.

But the hurdles to further integration are lower than we think. Brexit will remove from the EU the country most opposed to closer political union. Among the remaining countries, Europeans are often said to be against further integration. But this statement confuses a criticism of current institutions with a criticism of integration.

Eurobameter studies show year after year that EU citizens support more integration in matters where nations cannot be the solution, such as defence. They also support more democracy at the European level, such as the election of the president of the European Commission.

A deeper political union may actually be closer than it seems. Without any treaty change required, the European Commission presidential nomination process has the potential to radically change the nature of European politics by creating a pan-European debate about European policies.

The only thing needed for a leap towards further political integration is for the French and German heads of state to support it. This year may just deliver that.