Often it is just one artwork that kindles the idea for an exhibition.

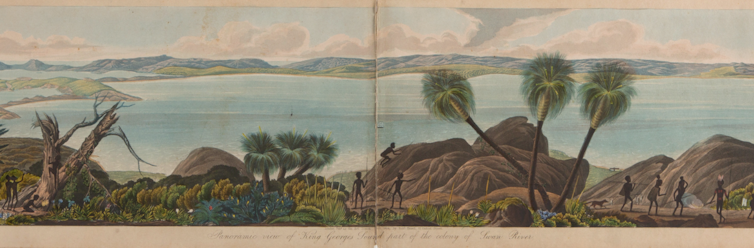

Robert Dale’s extraordinary panorama of King George Sound, engraved by Robert Havell and published as A Descriptive Account of the Panoramic View of King George’s Sound, and the Adjacent Country (1834), was the catalyst for a forthcoming exhibition at the Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery at the University of Western Australia.

The panorama is held in the Kerry Stokes Collection – though other copies can be found in a number of other public and private collections around the country. It encompasses notions of country and land management, of traditional ownership and colonial usurpation, of respect and its opposite. It also epitomises how a pictorial invention can impact on the popular imagination and assist in shaping consciousness.

A view of everything

In 1827, when Ensign Robert Dale of the 63rd regiment was preparing to visit the newly established outpost of Empire on the southwest coast of Australia, he likely took some time out to enjoy the spectacle of the painted panorama, a concept invented by Scottish entrepreneur Robert Barker and named by merging the Greek word pan (all) with hórãma (view).

Barker’s “view of everything” circular painting technique was presented in a specially constructed rotunda in Leicester Square in 1793. By 1826, both his original building and a rival rotunda on the Strand were offering a program of views, battles and tableaus from across Britain and the Continent. Indeed, by 1813 “panoramic” had come into common usage. For a young explorer like Dale this new medium must have seemed the perfect vehicle to describe newly “discovered” lands to a sophisticated London audience.

The great contradiction of being totally immersed in the scene while simultaneously detached is quintessential to the illusion of the panorama – and Dale arrived in the colony with this framing mechanism ready to be activated. After scurrying up the available vantage points he harnessed that lure of being there but distanced as a way of selling an interest in this new land to investors back home. His panorama shows a fertile landscape inhabited by friendly natives living in harmony with the newly-arrived soldiers.

However, this overt piece of propaganda masked the reality of those relationships. When the panorama was first shown it was hung alongside a gruesome souvenir – the severed head of Yagan, the Aboriginal leader – presented on a plinth in the foreground. Yagan had been hunted down, shot, skinned and then decapitated when he retaliated against the imposed authority of the new arrivals and their forcible acquisition of Aboriginal land. This juxtaposition undermined the fiction of harmonious relations that Dale was so keen to promote.

New panoramas

180 years later artist Chris Pease, a local Mineng Noongar man, has laid claim once more to his country by re-presenting Dale’s scene of cordial exchange and peaceful co-existence within a tainted paradise of felled Xanthorrhoeas and rudimentary town planning.

Confronted with this lie, Pease undertook a reinterpretation of the blatant land-grab by re-inscribing Aboriginal ownership over Dale’s panorama. Unfortunately, Pease’s work was unavailable for the exhibition but the artist agreed to its inclusion through reproduction in the catalogue.

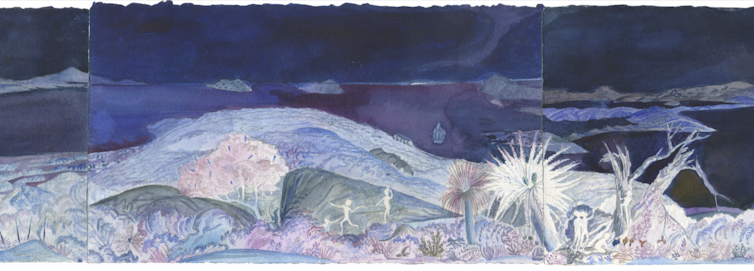

Gregory Pryor has also taken on the challenge of the Dale panorama in a series of three watercolours that similarly review the relationships depicted and moreover highlight the practical and cultural knowledge of Noongar people.

Created for this exhibition, Pryor’s first version is a chromatically negative rendering that highlights an alternative reading of that relationship and showcases the “fire-stick farming” technology Noongar people had developed. In the second version a photographic negative of the panorama on fire alludes to the destruction of that knowledge built up over millennia. The faux idyll depicted by Dale is then finally consumed by a heavy black pall of smoke that obliterates the scene in Pryor’s third version:

… the velvety blackness and silence (erasure) which is the culmination of fire.

The panorama format enabled Dale to communicate the scale of the enterprise he was selling to his audience; and for Pease and Pryor the panorama’s continuous scan provided the perfect structure to critique that project. The sense of “being there” is an important component of that process and 80 years after Dale’s engraving was published A.G Sands once again used the panorama format, this time to capture the first ANZAC fleet at anchor.

Coincidentally, it was in the same site – King George Sound – and he was able to simultaneously build morale and show solidarity with the venture because he involves his audience directly by suggesting they stand alongside him while he recorded the convoys departure.

As these artists prove, Robert Barker’s invention is a useful tool for involving us in the external world, but at one remove, where contemplation, interrogation and understanding are facilitated.

p a n o r a m a opens at the Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery at the University of Western Australia on May 3. Details here.