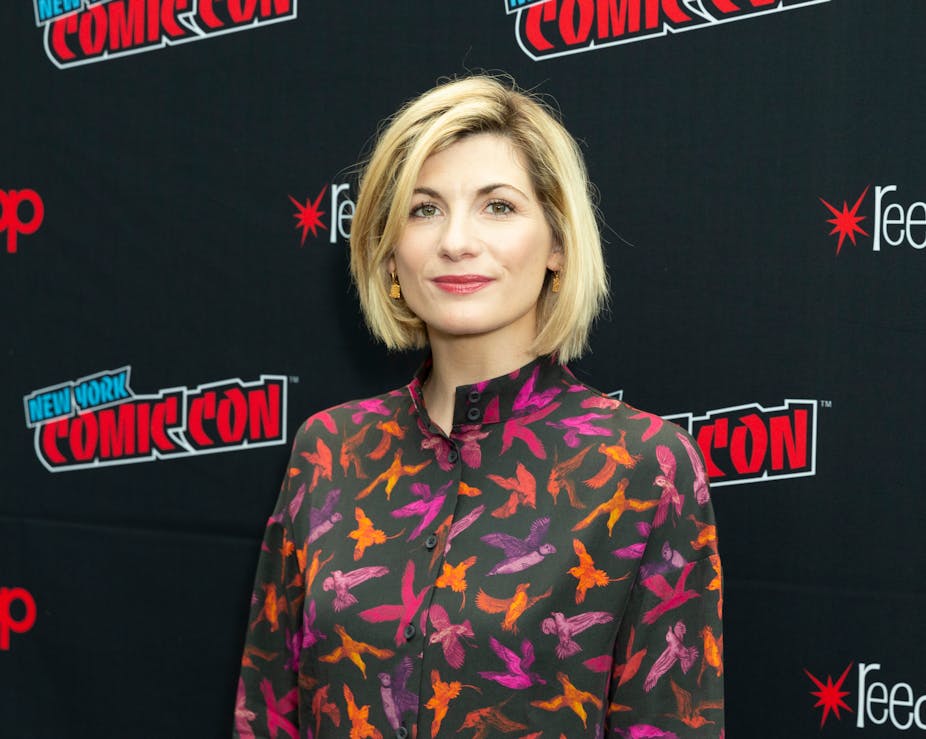

Doctor Who star Jodie Whittaker has become the latest actor to reveal how she has faced pressure to change her appearance. In a podcast, Whittaker disclosed that early in her career she was told to have a line on her forehead filled and was encouraged to wax her upper lip.

This is not a one-off occurrence, many other actors have spoken of how they have also experienced pressure to make changes to their bodies. In 2015, the late Star Wars actress Carrie Fisher joked that for her role in Episode VII – The Force Awakens the studio bosses didn’t “want to hire all of me – only about three-quarters”. Revealing that she had been asked to lose more than 35lb to reprise the role of Princess Leia, Fisher spoke of her frustration at working “in a business where the only thing that matters is weight and appearance”.

It’s not only female performers who find their appearance under scrutiny. When Simon Russell Beale played Hamlet for the National Theatre in 2000, one review led with the headline “Tubby or not tubby, fat is the question”. More recently, critic Matt Trueman was called out for “body shaming” actor Nick Holder in his review of Uncle Vanya. As Holder remarked, “I live in this body – I don’t hang it up like a costume on a rail at the end of the night.”

Holder makes an important point. Acting is embodied work and, as a result, actors carry their work with them at all times. In performance, an actor’s body tells a story through what it does. Whether that’s talking, singing, dancing, crying, shouting, or any other physically expressive act. It also tells a story through what it represents. And this closely relates to the social meaning attached to physical appearance.

Aesthetic labour

The physical and emotional effort that goes into making and maintaining an appearance for your work is known as aesthetic labour. It is ongoing work that extends beyond working hours and covers a range of activities, from putting on makeup to developing a six pack. It is not only actors who undertake aesthetic labour. Having “the right look” is a requirement associated with a range of occupations, often in the service industries, from baristas to flight attendants. For actors, though, the pressures of aesthetic labour are particularly acute because of the way their bodies make meaning in performance.

We’re probably all familiar with stories of actors changing their appearance for a particular role. From Kit Harrington growing a “Jon Snow beard” for Game of Thrones to Olivia Colman gaining weight to play Queen Anne in The Favourite, actors frequently make changes to their own bodies in order to embody their character.

But it’s not only in preparing for a specific role that actors undertake aesthetic labour. It might also be undertaken more generally, to create or maintain a body that fits the expectations of an industry in which, according to Fisher, “the only thing that matters is weight and appearance”. This focus on appearance can take a significant toll on an actor’s well-being. Hunger Games star Sam Claflin has spoken of being made to feel like “a piece of meat”, and feeling nervous and insecure about his body as a result.

Celebrities are not the only ones who face these pressures, however. Both male and female performers do at all levels of the industry – though they manifest in different ways. Researcher Roanna Mitchell found that drama school students will often try to make changes to their appearance, and that generally female students attempted to lose weight by dieting, while male students were more likely to embark on an exercise regime to build muscle. In this way, actors are responding to the demands of the industry as they see them.

In 2008, associate professor Deborah Dean reported that 48% of female and 35% of male performers believed that attractiveness is important in employment opportunities. This perception can put an enormous strain on actors, as they invest time, money, and emotional energy in generating what they see as a “castable” appearance.

My own current research project, Making an Appearance, examines the role of aesthetic labour within the UK performance industry. Next month, in collaboration with Equity Women’s Committee and the Centre for Contemporary British Theatre at Royal Holloway, I will be launching a survey which asks actors about the kind of changes that they have made to their bodies as part of their work. The aim is to explore the cost of this labour on actors. The research will also consider how issues of gender, ethnicity and age impact on the aesthetic labour actors undertake.

It is not actors alone who experience the consequences of this policing of their appearance. Actors reflect the world back to us, and if all performers are youthful and conventionally attractive, then that’s a distorted mirror we are looking at.

Whittaker rejected the calls for her to alter her body. She expressed a hope that things in the industry might change and that “we will just finally accept that we all look different and that is ace”. That would probably be a very good thing for everyone.