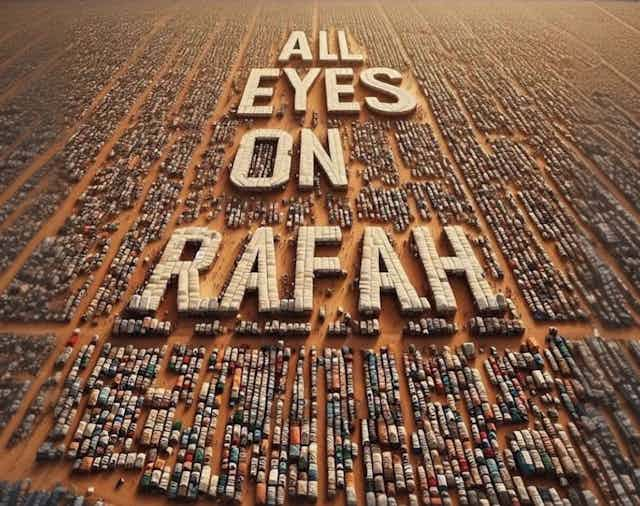

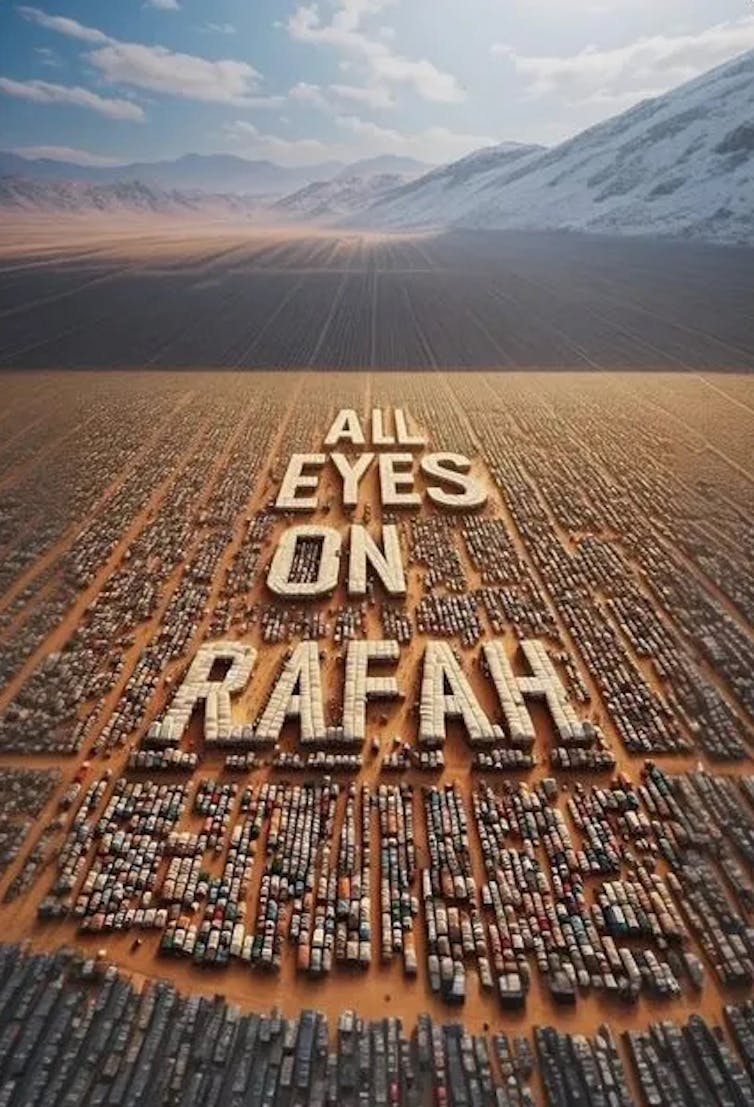

Over the past few days, one image has been shared at least 45 million times on Instagram. It shows an aerial landscape with hundreds of thousands of tents, pitched in rows, on red earth. In the centre, the tents align to form the slogan “All Eyes on Rafah”.

The immense popularity of this image provokes questions about the ethics of how we portray atrocity. Do we, as distributors of the image, have a certain moral responsibility? And why has an AI-generated image ultimately captured the world’s attention over the thousands coming directly out of Gaza?

Image origins and going viral

The image appears to have been made as a shareable sticker by Instagram user @shahv4012 in the days following an air strike by Israel that killed around 45 people in Rafah, including many women and children. Its relatively non-confronting nature means it has bypassed social media censorship (which might help explain its popularity).

Numerous media articles suggest the image is AI-generated based on certain irregularities. For instance, it is slightly blurred around the margins, the tents are uniformly distributed, and there is some inconsistency between the different areas of light and shadow.

The image borrows the tropes of aerial/drone photography, offering a totalising view of the earth from above, devoid of people. With its golden light and bucolic snow-capped mountains, it could have been plucked from a fictional world. Unlike the horrifying photos coming out of Gaza, there is no suffering to be witnessed.

Criticisms and moral responsibility

Criticisms have surfaced over why people are more comfortable sharing this AI-generated image over the countless photographs of Palestinian casualties taken by photojournalists and citizens who are risking their lives to document the conflict.

At the crux of this criticism is the demand that the images we share should authentically communicate the truth of the war. Critics contend the AI image sanitises the horrors, and call into question the virtue of people who would share this image, but not others.

In a post-truth era, the weaponising of images to deliberately spread misinformation has made AI images particularly contentious. At a time where there is concern over finding “the truth”, it becomes a moral question as to whether it is useful, or even appropriate, to represent war with an AI image.

In approaching this question, it helps to look at the history of picturing atrocity – and how the All Eyes on Rafah image circumvents the paralysing burden of real war photography.

War images are (very) confronting

We’ve seen images of warfare in films, video games and on the news: think of the hunt scenes from the raid on Osama Bin Laden, the so-called images of “weapons of mass destruction” in the Iraq War, or the 2015 photograph by Turkish journalist Nilüfer Demir of drowned Syrian toddler, Alan Kurdi.

Or consider some of the most explicit representations of atrocity popularised by the media, such as Nick Ut’s iconic 1972 photograph, Napalm Girl – often referred to as the image that changed the Vietnam War – or Malcolm Browne’s photograph of the self-immolation of monk Thich Quang Duc.

Such examples reveal the power of images to capture tragedy. But they also provoke questions around voyeurism and the ethics of witnessing suffering. For instance, for people in the West, such images may normalise the depiction of those in the Middle East and Global South as always being subjected to war and atrocity.

The earliest discussions on the ethics of viewing and sharing images of atrocity came in the late 1960s, during the Vietnam War, from American writer Susan Sontag. Sontag initially said photographic representations of war “anaesthetised” people to the reality of suffering. She wrote:

To suffer is one thing; another thing is living with the photographed images of suffering, which does not necessarily strengthen conscience and the ability to be compassionate […] after repeated exposure to images it also becomes less real.

However, she later revised this position following a first-hand experience of the 1993 siege of Sarajevo.

What is war imagery for?

The All Eyes on Rafah image enables social media users to share their solidarity in a politically “safe” and non-contentious way. The image’s somewhat diluted nature has no doubt contributed to its rapid spread.

In assessing it as a war image, we must ask the question: what is an image of conflict supposed to do, and does it do this?

We might hope such an image would stop the war altogether, but this is probably unrealistic. Perhaps, then, the sharing of the image to raise awareness and express solidarity is the most we can hope for – even though, as Sontag said, such images are ultimately destined to fade from view.

Or, it might be more productive to instead think of this AI image as a symbol, or a new form of graphic storytelling. Similar powerful symbols in the past have been granted meaning through a collective investment in them, such as the black square of the Black Lives Matter movement, the raised fist symbol of the anti-Apartheid movement, or the appropriation of the pink triangle to represent the AIDS movement.

Maybe this is a better way to approach AI images in the context of war, by untethering them from photography’s connection to “the real” spectacle of war. As long as the real images are also shared and centred, there is no harm in using a symbol to signal solidarity.