This article contains spoilers and discussions of trauma and homophobia.

On the surface, All of Us Strangers, directed by Andrew Haigh, is a dark and twisty love story. Underneath, there is the often-present storyline seen in queer cinema: that of trauma and tragedy.

All of Us Strangers follows lonely middle-aged gay man Adam (Andrew Scott), struggling to come to terms with his tragic past and sexuality. Adam is a screenwriter, attempting to use his craft to work through his trauma, but his solitary life is interrupted by his new neighbour Harry (Paul Mescal).

Through a dreamworld-like exploration, Adam experiences the companionship and love accepting his homosexuality would bring, all the while visiting his dead parents in an “I see dead people” Sixth Sense fashion.

Ultimately, the story ends with the realisation Harry, like Adam’s parents, was actually dead all along, and the film leaves us wondering if Adam himself is a ghost, too.

LGBTIQA+ audiences are accustomed to seeing themes of loss, grief, homophobia and tragedy play out on screen, and this film is no exception. While it explores these themes through a beautiful, haunting ghost story, gorgeous cinematography, affective music score and captivating performances, it still reinforces the narrative queer people cannot live happy lives.

Read more: All of Us Strangers: coming to terms with the grief and trauma of being gay in the 1980s

Queer representation

Queer representation in mainstream media has historically been marred by negative stereotypes, tokenistic representation and death. In my recent interactive documentary, Queer Representation Matters, queer media scholars and queer screen storytellers share how queer characters are often relegated to roles characterised by tragedy or trauma, perpetuating harmful tropes like “bury your gays”.

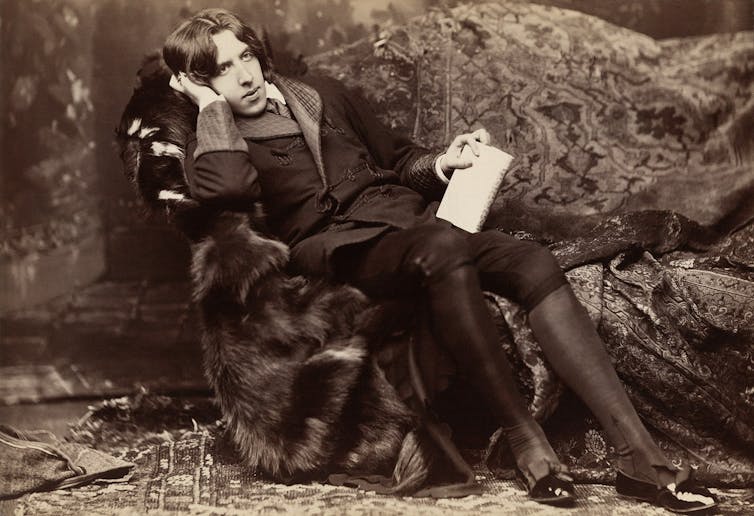

Bury your gays is a storytelling trope that sees LGBTQI+ characters die, often to propel the story forward for a cis, heterosexual character. We can first find these stories in late 19th century literature such as Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890).

It gained traction in the early 20th century, in Lillian Hellman’s The Children’s Hour (1934) and Vin Packer’s Spring Fire (1956) (although she doesn’t die, just ends up institutionalised), and continues to appear in novels, plays, films and on television.

Films such as The Hours (2002), Philadelphia (2003), Brokeback Mountain (2005), A Single Man (2009) and Black Swan (2010) are all films about a queer character who suffers and dies.

You may remember some of these much-loved, yet killed-off TV characters: Villanelle from Killing Eve (2018–2022), Poussey Washington from Orange is the New Black (2013–2019) and Lexa from The 100 (2014–2020).

Online queer news site, Autostraddle, have compiled a list of the 230+ dead queer female TV characters, which continues to be updated with each death.

Essentially, for queer people, it starts to feel like you can’t have queer representation without someone dying tragically at the end.

A 2023 report from Screen Australia shows only 7.4% of main or recurring characters on Australian scripted TV from 2016–2021 were identifiably LGBTQI+, and although there have been improvements in representing more complex and inclusive queer stories on Australian television, we remain quite conservative in depicting queer sex and diverse genders.

Queer people will have different and complicated responses to queer death on screen. The result of the bury your gays trope is many queer people are left feeling that being queer means you are destined for tragedy. Witnessing another queer death on screen can make us revisit past wounds and experiences.

Read more: We studied two decades of queer representation on Australian TV, and found some interesting trends

We need diverse stories

Tropes will always exist in storytelling, but by having more diverse queer filmmakers telling more diverse queer stories, audiences will have a more balanced narrative about queer life (and life expectancy).

So, do these themes of trauma, tragedy and queer death mean films like All of Us Strangers fall into the bury your gays trope? Not necessarily, no. Here, Harry’s death is not propelling a straight character’s story forward.

It is also necessary to have sad stories about queer characters. Stories that show the queer experience in different social and historical contexts are important to understanding the struggle for LGBTQI+ liberation.

While All of Us Strangers may reinforce the narrative queer people cannot live happy lives, there are moments of tenderness, vulnerability and hope in the film. The true value of the story lies in its creation by gay filmmaker Haigh.

When a gay man is able to tell the story his way, the story becomes more authentic.

Haigh’s ability to create truthful conversations between Adam and his parents, cross-generational romance, and the desire to heal persisting wounds, demonstrates the value of the authentic lived experience.

It is important to reflect the tragic queer lived experiences. But when these stories are saturating our big and small screens we are not seeing the alternative – the queer resilience, resistance, joy, hope, creativity, potential and triumph.

We need to see stories that challenge the narrative that being queer ultimately leads to pain, trauma and tragedy. We need to see we can also live long and happy lives, so we can believe we can have the happy ever after.

Read more: All of Us Strangers: heartbreaking film speaks to real experiences of gay men in UK and Ireland