“Gabo, the great absent presence on this day, who was the shadow architect of many peace efforts and processes, could not make it to live this moment, in his beloved Cartagena, where his ashes rest. But he must be happy watching his yellow butterflies fly above the Colombia of his dreams, our Colombia, finally reaching, as he said, ‘a second chance on earth’.”

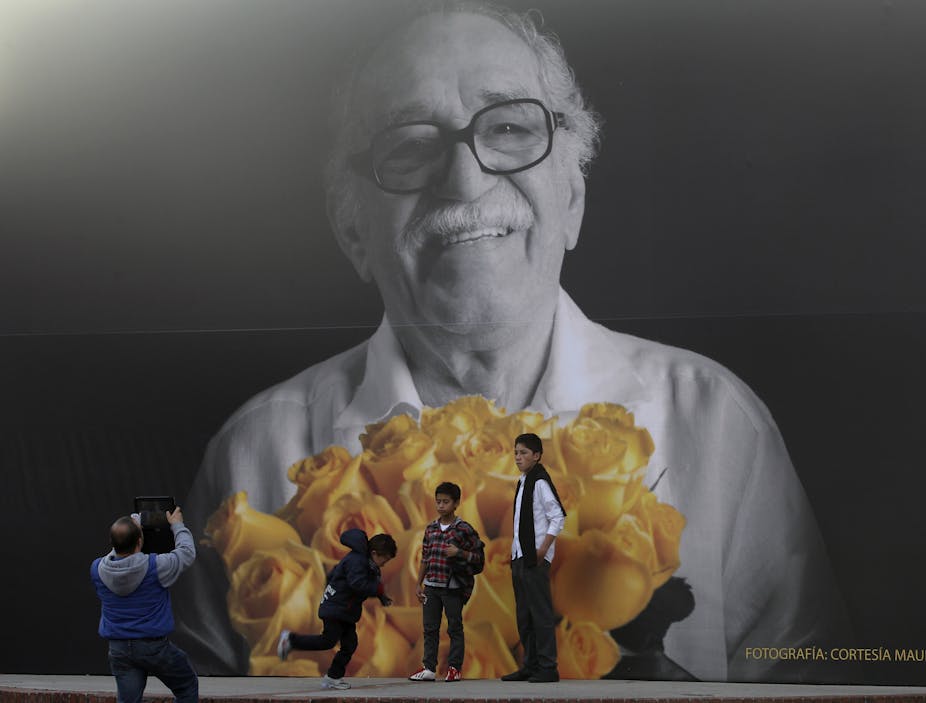

So proclaimed Colombian president Juan Manuel Santos in honour of author Gabriel García Márquez at the September 26 signing of the Colombian peace accords with the FARC – an agreement that just days later would be voted down by the Colombian people.

FARC guerrilla leader Timochenko also cited Gabo, as García Márquez is affectionately known in Colombia, ending his speech by welcoming this “second chance on earth”.

It is not by chance that the author of this Latin American literary movement – and my country’s first Nobel laureate – was quoted by both leaders at the signing of the doomed accords.

The October 2 plebiscite may have been seen outside of Colombia as an example of Colombian magical realism, but as a literature professor I have to wonder what Gabo would have made of the No vote, knowing so well, as he did, the soul of the Colombian people.

Colombians are well aware that peace is good for the country. But still they didn’t vote for it. Many blame the outcome on the polarisation caused by the negotiations in Havana, but Colombia has always been a society divided into opposite groups: religious and nonreligious; liberals and conservatives; rich and poor; guerrillas and non-guerrillas; warmongers and peacemakers.

Gabo, I suspect, would not be surprised by what happened on October 2. He knew Colombia to be a place of extremes. In One Hundred Year of Solitude, he scrutinises the many aspects of Colombia’s fratricidal conflict in the political field. Colonel Aureliano Buendía, he writes, “promoted 32 armed uprisings and he lost all of them”. At the end, he recognised that pride, or “something that means nothing to anyone,” is the only reason for fighting.

Another Colombian writer, Héctor Abad Faciolince, has said that Santos and Uribe “covet the same thing: to be themselves, each of them, the protagonists of the agreement, and to prevent their political adversary from being it. It is a human matter, too human, pure vanity. Peace, yes; but only if I am the one who signs it.”

This rivalry is, alas, only exacerbated by Santos winning the 2016 Nobel Peace Prize.

Gabo also recognised that Colombian hearts are usually unwilling to forgive and to make real change. After Colonel Aureliano Buendia signs the armistice in One Hundred Years of Solitude, the regular army slaughters those involved in the party coronation of Remedios la Bella, just because someone shouted “Viva!” for the Liberal Party and the old Colonel.

This fact is epitomised by one of the most popular plays in Colombian history. Guadalupe, Years Without Count is a collective creation of Teatro la Candelaria. The plot centres on the head of the liberal guerrillas in the country’s Llanos region. His rebellion emerged in response to the 1948 assassination of popular leader Jorge Eliécer Gaitán who, along with his troops, surrendered weapons in 1953, only to be killed three years later by the secret police.

Colombians’ inability to forgive was also evident more recently, in the 1990s, as the armed groups that demobilised then suffered continuous hostility, as well as a lack of support for reintegration into society. Between 1984-1997, the Patriotic Union was subjected to a political genocide.

So a historical, as well as literary, analysis shows that Colombian society is often not ready to forgive and to reintegrate those who have attacked it.

We have to admire García Márquez for his great capacity to capture Colombia’s reality; indeed, what he wrote in yesteryear is still apt today, and perhaps remains a prophetic voice for what will come tomorrow.

The emotional rollercoaster caused by news of recent days and weeks almost seems to have been anticipated by his prose:

It was as if God had decided to test their sense of wonder, and was keeping the inhabitants of Macondo in a permanent sway between joy and disappointment, doubt and revelation, to the point that nobody could know with certainty where the limits of reality were. (One Hundred Years of Solitude)

This is exactly what Colombians have experienced in recent days: the exultation of signing the Havana Agreement on September 26; the disenchantment of witnessing those opposed to the peace agreement claim victory in the referendum of October 2; and now the enthusiasm for the awarding of the 2016 Nobel Peace Prize to president Juan Manuel Santos, whom the newspaper El Tiempo describes as “a warrior who has always sought peace”.

Gabo’s magical realism could only have emerged in just such a country, a place of fierce contradictions, surprise endings, pain, grief, and exuberance. As one commentator wrote on Twitter: “Such are life’s ironies; we now have two Nobel laureates in Colombia: one of literature, in a country that does not read, and one of peace, in a country that does not forgive.”

(The average number of books read per person in Colombia every year is very low. According to the National Department of Statistics, 13 millions of Colombians read just one book per year.)

A rereading of García Márquez vividly reveals his views of war (“it was easier to start a war than to end”, he wrote in One Hundred Years of Solitude), and on the most important issues in the Havana negotiations (“LAND, INFLUENCE OF CLERGY, FAMILY”).

As a nation, we welcome the Nobel Peace award to Colombia if it means the advent of reconciliation. But I have no doubt that Gabo remains the country’s favourite winner, because he illuminates the path for unity and happiness for Colombians.