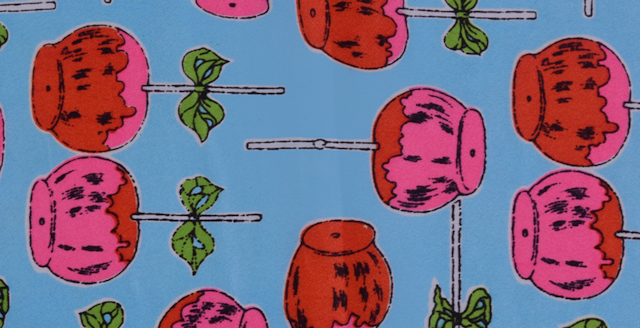

The printed fabrics created by Andy Warhol during the 1950s and 1960s reveal the artist’s recurring fascination with quirky motifs rendered in his trademark inky lines. This fresh, exciting style was acquired while working as a commercial illustrator in New York’s fledgling advertising industry.

Before establishing himself as the seminal influence in the pop art movement – best known for his silkscreens of 1960s cultural and consumer icons such as Marilyn Monroe and Campbell’s soup – Warhol had an extremely successful career in illustration and graphic design.

But it is only recently that his commercial textile designs have been unearthed – few even realised they were part of the artist’s story. Now these designs are being showcased in Andy Warhol: The Textiles at the Dovecot, a design and textile gallery in Edinburgh, featuring 35 of Warhol’s whimsical patterns.

Creating the look

Things start off strongly showing lithographs and early textile designs on paper, juxtapositioned with lengths of repeating-pattern fabrics and vintage garments. These set the scene for a chronological display of Warhol’s illustrative approach to textile design, and the translation of his imagery onto a variety of garments gives the exhibition a nostalgic thrift-shop appeal.

Lots of cool little details abound. For example, vistors learn how a typo from an advertising job misspelled his original name – Warhola – cutting off the “a”, accidentally creating the name that would become forever synonymous with pop art. This is reflected in the inclusion of a printed advertising mail-shot he designed for the Moss Rose Manufacturing Company in 1949 featuring his Czechoslovakian birth name in full.

The start of the exhibition focuses on the timeless yet largely unrecognised process of converting artwork on paper into patterned fabrics for clothing. “Happy Bug Day” (1955-56), a textile print produced by D.B. Fuller & Co, highlights the journey of an illustration as it translates to a repeating pattern that eventually becomes a swimwear piece typical of the 1950s.

Warhol’s process is celebrated throughout the exhibition by examining the different stages of textile making and clothing production. Throughout fashion history, it is often a bold or striking print that “makes” a garment, even though textile designers are rarely acknowledged. More usually it is fashion designers who receive the acclaim.

Turning this on its head, there is much referencing around the textile manufacturers creating the fabrics, and much less focus on garment designers or fashion boutiques that would have stocked the pieces.

Thanks to their vintage nature, some of the hanging fabric pieces and garments on show would look just as at home in a charity shop window. But it is the garment details that provide some of the most visually pleasing and exciting use of textiles in the exhibition space.

“Pens, pencils and brushes” (1956) and “Perfume and scent bottles” (1958-59) are two beautiful examples of printed fabrics showing how clever manipulations create wonderful effects by distorting the uniformity of graphic patterns through fabric pleating, for example.

Often using quirky motifs such as socks, potted plants and ice cream cones, Warhol rendered them with an established “blotted line” technique or a simple print stamp. These bright quirky designs brought some much-needed colour to a drab post-WWII America, exuding a fresh, optimistic and light-hearted quality.

But Warhol’s image-making could easily be mistaken for the work of a contemporary children’s book illustrator and would look equally at home on a pattern-obssessed Instagram account in 2024.

Like many other professional designers, Warhol often used variations and combinations of ideas that he had employed in other graphic works. The exhibition highlights the skilled professional practice of generating fabric colourways with repeating patterns, including an example of fabric with large colourful butterflies (1955-56), again produced by D.B. Fuller & Co.

Finding Warhol

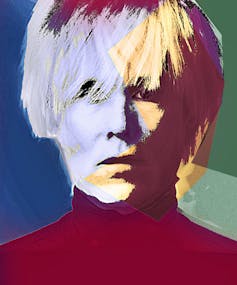

Alongside the textiles and garment collections the exhibition also includes huge back-lit black and white portraits of Warhol that act as much-needed context for the celebrity artist who was then just finding his way with his commercial designs. This was long before before he embarked on his Factory exploits where he created experimental works across a variety of media that would garner him fame and notoriety, and secure his place in art history books.

The final pieces in the exhibition bring together what are believed to be his last commercial textile designs, translated into predominantly silk and synthetic fabrics by the Stehli Silks Co, dating from 1962-63. These exhibits show much closer links to his pop art oeuvre, with clashing colour and more contemporary culture references for motifs, such as pretzels on printed silk.

As a textile designer who has seen a number of exhibitions in this space, it’s hard not to compare this show with the beauty and technical innovation behind other Dovecot shows. For me these high points include Making Nuno, which showcased the work of Japanese textile designer Sudō Reiko a couple of years ago, and the iconic approach to wallpaper sampling in The Art of Wallpaper: Morris & Co.

Perhaps unlike these exhibitions, Andy Warhol: The Textiles doesn’t claim to present the pop art pioneer as a pioneer of textile design too. But it does bring a most enjoyable and fresh perspective to his work, revealing the DNA and origins of Warhol’s iconic style.