Abortion has become an increasingly polarized, political issue in the United States since 2022, when the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, which guaranteed the constitutional right to an abortion. This decision threw the question of abortion rights back to states.

Ohio voters will cast ballots on Nov. 7, 2023, to determine abortion rules in their state, joining six other states that have put the decisions before voters in ballot initiatives since 2022.

Currently, Ohio’s constitution does not mention abortion. Ohio residents will vote on “Issue 1,” which would amend the state constitution to explicitly protect an individual’s right to get an abortion. The amendment would still allow the state to prohibit abortion after a fetus is considered viable, with an exception when the health of the pregnant person is at stake.

The initiative is supported by a coalition of abortion-rights organizations, collectively called Ohioans United for Reproductive Justice.

Some anti-abortion activists in Ohio have said that Issue 1 is “too radical” for the state. But an October 2023 survey showed that 58% of likely Ohio voters support Issue 1.

I am an American politics scholar who focuses on how groups outside of government attempt to influence policy.

Since the Supreme Court overturned the federal right to get an abortion, I have interviewed 45 anti-abortion activists across the country and collected Facebook data from approximately 190 organizations. I wanted to better understand how anti-abortion groups are working in a post-Roe v. Wade world to ban abortion.

Prominent anti-abortion groups continue to reference religion, and specifically Christianity, in their arguments against abortion. But I found that these activists also recognize that framing abortion as a human rights issue may appeal to a broader audience.

Perceptions of the anti-abortion movement

Religious objections to abortion center around the sanctity of human life and the belief that humans are made in God’s image. To end a human life, including the life of a fetus, is to play God.

According to a 2019 poll, 77% of Americans believe religion has some or a lot of influence on U.S. abortion policy.

In my interviews, anti-abortion rights activists said they understood that the public views their movement as anti-woman and driven by conservative Christians. More recently, the movement has adopted pro-woman messaging to counter the perception that they do not support women.

These organizations are increasingly choosing to speak less about religion and more about human rights and science to combat the narrative that the anti-abortion movement is solely a Christian movement.

This movement does have a religious history – the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops created the predecessor of one of the most well-known anti-abortion organizations, the National Right to Life Committee, in 1966.

In the 1980s, Operation Rescue, which blockaded abortion clinics and had thousands of their activists arrested, brought an evangelical religious fervor to the anti-abortion movement.

Stopping abortion was seen as a Christian duty, even if it meant resorting to violence.

The changing role of religion

The religious environment in the U.S. has changed in recent decades, however.

While evangelicals remain a powerful voting bloc for Republicans, the percentage of Americans identifying as Christian has declined over the past 50 years from 90% to 63%. At the same time, the percentage of Americans who identify as religiously unaffiliated has increased from 5% to 29%.

In 2020, less than half of Americans belonged to a church, synagogue or mosque – marking an all-time low in affiliation with a religious institution since 1940.

For anti-abortion activists, this means fewer people may connect to their religious appeals. One activist I interviewed put it bluntly: “Why talk the Bible to people, many people, who say the Bible is a fairy tale?”

What anti-abortion organizations say

My research shows that anti-abortion organizations in the U.S. fall into one of three camps. Some are openly religious. Others may have religious staff, but refrain from using religion in their advocacy. A small proportion outright reject the use of religion.

I analyzed how anti-abortion organizations use Facebook to promote their work. At least on this social media platform, most anti-abortion organizations do not use religious language.

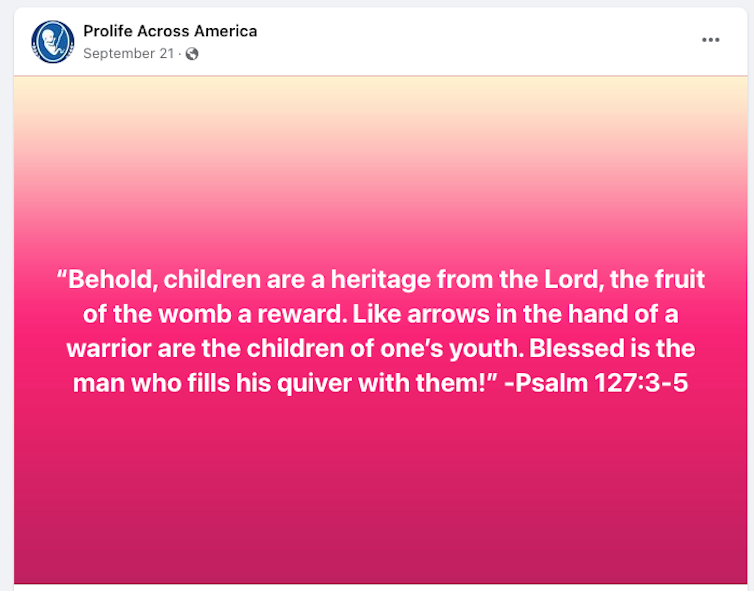

Between June 2022 and September 2023, 193 anti-abortion groups posted 44,639 times on Facebook. Approximately 11% of these Facebook posts made explicit religious references, ranging from Bible verses to prayer requests.

Some organizations use religious references in nearly all of their Facebook posts, while other groups make only passing references to religion.

Texas Right to Life, for example, posted 770 times between June 2022 and September 2023, and 50% of its posts mentioned religion. In contrast, the group Ohio Right to Life posted 586 times in the same time period. Only 8.7% of their posts mention religion.

More than 15% of the 193 anti-abortion organizations in my sample, however, make no religious references in their Facebook posts from June 2022 through September 2023.

Indeed, the majority of the 45 activists from anti-abortion groups I spoke with said they kept their religious beliefs separate from their activism.

As one anti-abortion activist told me, when someone finds out “you believe that all life is created in the image of God, they completely dismiss you.”

Other findings

Most of the activists I interviewed said their organization does not have a formal stance on religion. Approximately one-quarter of the 45 activists I interviewed, however, said their organizations are explicitly Christian.

When asked about the choice to frame anti-abortion arguments around faith, one advocate said, “We 100% present the faith and the theological argument of things. Yeah, part of our culture is being Catholic.”

This advocate continued: “We understand that we also have a responsibility before God on these subjects, so we’re not going to shy away from that.”

A few interviewees stressed that they are not religious. One described herself as an “atheist, vegan pro-lifer.”

Instead of using religion to bolster their arguments against abortion, these activists frame abortion as a human rights issue. For them, any loss of human life is tragic, whether it is from abortion, war or the death penalty.

This kind of framing could help the anti-abortion movement shift conversations about abortion away from religious beliefs.

Ohio’s vote

People in all six states that have voted on abortion since 2022 have affirmed broader abortion rights. But Ohio is the first red state to vote on adding a right to abortion to the state’s constitution.

Local anti-abortion groups like Cincinnati Right to Life are pushing back against Issue 1, saying, for example, that the amendment is too wide-reaching, and that “Issue One will only hurt women & children and not help them.”

Ohio Right to Life has framed Issue 1 as a matter of safety in their Facebook posts.

Ohio voters will be the ones to decide which way to move the issue forward.