A staggering increase in the number of Asian hornet sightings in the UK has beekeepers and wildlife lovers there reeling. But the invasive species poses a substantial threat to beekeeping and honey production across Europe.

Asian hornets (Vespa velutina), which are native to south-east Asia, are a top predator of honeybees. Just one Asian hornet reputedly can hunt down and eat up to 50 honeybees a day.

Research estimates that Asian hornets could cost the French economy €30.8 million (£26.4 million) every year in a worst case scenario.

But their menace extends beyond bees in a hive. Asian hornets also prey on native pollinators such as bumblebees, so can have a serious impact on the pollination services these creatures provide.

Asian hornets don’t just eat other bees. They also scare them away from flowers. One study found that flower visits by bumblebees and hoverflies dropped substantially in the presence of these predators.

Asian hornets were first recorded in the UK in 2016 when worker hornets were seen foraging at an apiary near Tetbury in Gloucestershire. Since then, vigilant members of the public and beekeepers have found and identified 43 Asian hornet nests in the UK – mainly in southern counties such as Kent, Hampshire and Devon.

So far, there have been more confirmed UK sightings of the Asian hornet in 2023 than there were in all the previous years combined. Despite the occasional suggestion that the Asian hornet may have become established in the UK, there is no evidence yet that these insects can survive British winters.

The spread of invasive Asian hornets mirrors a global trend. According to a recent report by the Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, invasive species are linked to 60% of global plant and animal extinctions. Their implicit economic cost stands at around US$420 billion (£335 billion) each year.

Read more: UN invasive species report reveals scale of threat to nature and people – and how to manage it

Crossing the border

The Asian hornet (also known as the yellow-legged hornet) first came to Europe in 2004, where it was spotted in the Lot-et-Garonne region of south-western France. It was supposedly brought to Europe by mistake in a shipment of imported pottery from China.

Asian hornets have since spread into several neighbouring countries, including Spain, Portugal, Germany and the UK. The UK sightings so far in 2023 are clustered around the coast in Kent, Dorset, Hampshire, Plymouth and Weymouth.

Genetic analyses carried out by the National Bee Unit, which runs bee health programmes in England and Wales, suggest that the Asian hornets found in the UK all have the same heritage as the population on mainland Europe. This implies that they are crossing the channel from France on maritime winds with regular re-invasions each year.

It’s plausible that the higher summer temperatures seen throughout Europe in 2023 may have driven the recent increase in sightings in the UK. Hornets need warm weather, like they have in Asia, to survive. So warmer summers make it more likely that they will cross over to the UK from Europe and survive long enough to be spotted by people.

Scientists aren’t yet sure what has caused 2023’s mass invasion. But a study, led by the UK Centre for Ecology and Hydrology, to investigate the underlying factors is underway.

Why they’re a threat

Beekeeping is not just a European enterprise. There are over 45 million honeybee hives across Asia, housing nearly half of the world’s honeybees. All of these bees are living with the Asian hornet without much issue.

So why are European beekeepers so concerned about an insect that is mostly a piece of everyday life for beekeepers in Asia? The secret is in the breeding.

European beekeeping has never had to account for a significant predatory threat like the Asian hornet. The European hornet (Vespa crabro), for example, looks similar to the Asian hornet and is nearly double the size. But this species poses very little threat to people or to bees.

The giant woodwasp (Urocerus gigas) is found throughout Europe too, and can grow to about 5cm long (roughly the size of a house key). However, this species is completely harmless and quite gentle-mannered.

Due to the scarcity of native predators, European beekeepers have been intentionally breeding bees that are easier to handle and capable of producing larger quantities of honey. Consequently, these bees are defenceless against a formidable predator like the Asian hornet.

Several bee species throughout Japan, China and South Korea are significantly more adept at warding off Asian hornet attacks than their European counterparts. The giant honeybee (Apis dorsata) is so large that it uses its body mass to smother a hornet. Meanwhile, her sisters swarm the invader, gradually heating it up and cooking it alive – quite an effective defence.

How to spot them

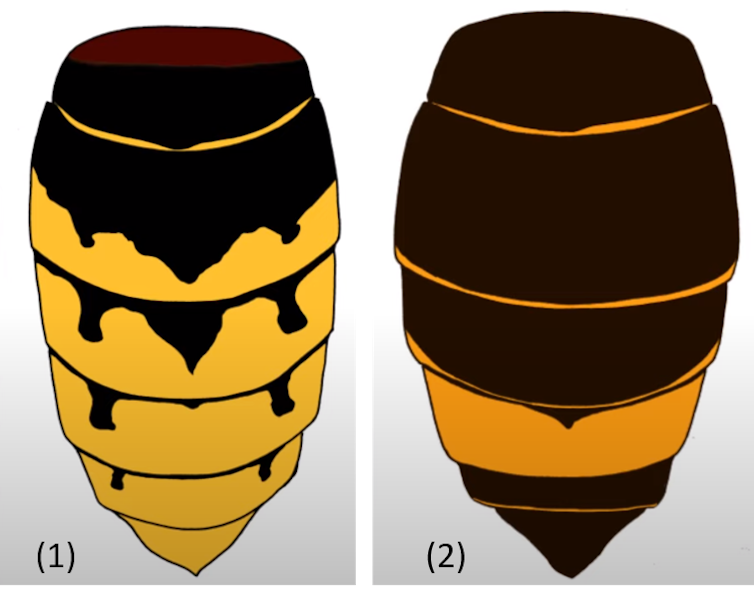

Asian hornets are slightly smaller than the European hornet. They have a dark brown thorax, yellow-tipped legs, a black head and an orange face. However, the Asian hornet’s potentially most distinctive characteristic is its abdomen, which is dark brown with a fourth segment that is almost entirely orange.

If you suspect you have an Asian hornet in your area, the UK Centre for Ecology and Hydrology has been spearheading a national monitoring programme. Remember to include full location details.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 20,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.