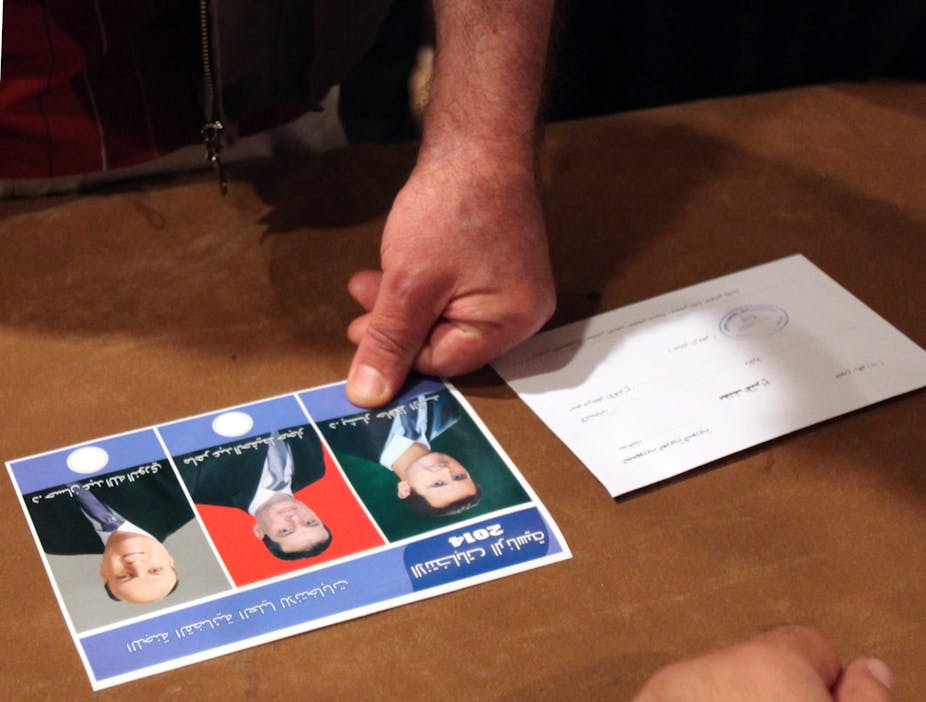

There are three candidates running in Syria’s presidential election: the incumbent, Bashar al-Assad and two challengers, Maher Hajjar and Hassan al-Nouri. In reality there is only one, Assad. The other two are candidates approved by the regime who have had little chance to campaign, but are intended to give some semblance of democracy to a process that is little more than a charade.

Across much of rural Syria – and in some of the urban areas – the regime has no power, with diverse rebel groups in control. This means that in reality perhaps 40% of Syrians within the country will not be taking part. Add to that the millions displaced within and outside the country and it is obvious that this is a minority activity at best.

Even so, the real point of staging the election is to consolidate power by sending a message to the wider international community that the Assad regime feels secure and confident, believing that it is slowly but surely winning the war. Whether this is true is another matter, but the harsh reality is that Assad is certainly more firmly in power than at any time since the war began more than three years ago. He retains the support of Iran and Russia, is greatly aided by Hezbollah militias and also has a steady flow of Shi’a paramilitaries coming from Iraq.

He is also facing an increasingly divided opposition. Many of the more secular and nationalist elements of the rebel forces are facing declining morale as they lose towns and districts to government forces, a result being that the main opposition is coming increasingly from radical Islamist groups such as the al-Nusrah Front and ISIL.

The former is loosely allied to the al-Qaida vision but the latter is even more extreme and links with groups that now control significant territory in Iraq. Taking the two countries together, we are now in the remarkable position of seeing radical Islamist groups having free rein across an area larger than the UK, right in the heart of the Middle East.

West sits on its hands

It is largely for this reason that criticism of the Assad regime by western governments, including the UK and US, is currently quite muted. Senior politicians go through the motions of condemnation, but the reality is that there is now a declaratory policy and a very different implementation policy. The first is for public consumption and involves the usual comments on the utterly unacceptable nature of the regime, but the second is a reluctant acceptance that if the regime fell, the end result would be worse. Put bluntly, the West sees it desirable for the regime to survive, at least for now.

Behind this lies the change in the opposition, with the rise of the Islamist elements – and within this is one particular trend. This is the manner in which thousands of young men, including many hundreds from Western Europe, are travelling to Syria to fight with the rebels against the Assad regime. Some of them get killed and others become disillusioned, but many of them survive, eventually to return home where they constitute a growing cohort of young men dedicated to radical change.

It has happened before. In the 1980s many foreign fighters went to join the Mujahidin fighting the Soviet occupying forces in Afghanistan and some of them went on to be dedicated to the al-Qaida movement. Two decades later, the same thing happened in Iraq although with one crucial difference. In 1980s Afghanistan, the foreign fighters were challenging low-morale Soviet conscripts in a rural environment, whereas in Iraq in the mid-2000s they were fighting well-trained and heavily armed US volunteer troops and Marines in an urban insurgency. Some of those young men have since been involved in Islamist paramilitary conflicts in Iraq and Syria, joined now by new recruits from across the world.

What this all comes down to is the blunt and uncomfortable reality that western governments are now reluctant to support any of the rebels, even the more secular elements, but are not willing to say so. There is no liking whatsoever for the Assad regime in Damascus but there is an even greater concern with what will happen if it falls. This is also a view that is increasing among many Syrians after more than three years of devastating conflict, further adding to the power of the regime.

The hugely experienced UN diplomat, Lakhdar Brahimi, has resigned from his post as UN mediator, believing that the chances of getting a settlement are close to zero. Quite apart from all the internal issues, Syria remains a double proxy conflict with the regime backed by Iran and Russia and the rebels backed by the Saudis and, to a variable extent, the West. Any kind of mediated settlement will be impossible without external commitment at a level way beyond anything so far achieved.

Meanwhile, the death, destruction and suffering continues.