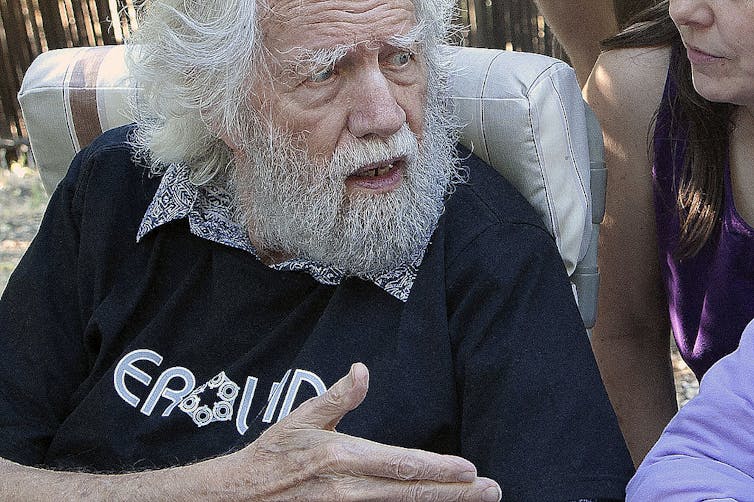

More than 40 years ago, the synthetic chemist Alexander Shulgin said that, in the future, underground researchers would synthesise novel psychoactive stimulants. Shulgin’s prophecy came true. Over the past ten years, we have witnessed the rapid emergence of novel psychoactive substances (NPSs), sold over the internet and in “head shops”. The content, interactions, side effects and abuse potential of these NPSs are often unknown, not only to users but also to doctors.

Last week, the Psychoactive Substances Act 2016 came into force in the UK. The law says that if a person produces, distributes, supplies, imports or exports a substance capable of having a psychoactive effect – nicotine, alcohol, caffeine and medicinal products are excluded – they could receive a prison sentence of up to seven years. Possession is not an offence.

Worryingly, the government delayed this legislation because it had not established exactly how substances will be tested for psychoactivity. This will be difficult given the wide range of the psychoactive substances that fall under this bill. However, enforcement of this bill will be vital to eradicate the open sale of NPSs on high streets, on UK websites and in our prisons. But the fact that Ireland has struggled to enforce their NPS law – in fact, use among young people has gone up since their bill was introduced in 2010 – is cause for concern.

If the law is consistently enforced, the fear of imprisonment will no doubt deter open high street and internet sales of NPSs in the UK. But prohibition will not address supply of NPSs via the largely untraceable area of the internet, the dark web nor will it address drug demand – the basic human desire for seeking pleasure and altered states of consciousness.

Demands for well-known NPSs made illegal under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971, such as mephedrone, have not significantly changed in the last three years, indicating that simply making something illegal seems to have little impact on demand. There is also an early indication that future demand is unlikely to shift. A survey of 1,000 16-24-year-olds found that nearly two thirds of respondents said that they are likely to continue to use NPSs, despite the ban.

Surely then the odds are stacked against this bill influencing NPS demand unless there is also a clear communication of the consequences of consuming NPSs. Also, we must not lose sight of the fact that far more prevalent “lawful” psychoactive substances taken in the UK, alcohol and tobacco (exempt of this ban) are more harmful than many illegal drugs.

This new bill makes no distinction between very harmful psychoactive substances, such as synthetic opiates, and relatively safe ones, such as laughing gas (nitrous oxide). Ironically, while alcohol is legal, “alcosynth”, being developed as a safer alternative to alcohol, is now banned.

Surely the message the government needs to convey, alongside any drugs prohibition bill, is that all substances (legal or illegal), including foods, drinks and medical products are harmful if consumed in the wrong amounts. Even water. There have been a number of cases where people have died as result of drinking too much water (hyponaetremia) while on ecstasy.

Drug education is the key to prevention

The misleading term, “legal highs”, has not helped the perception that there has been some process of assessment deeming them safe for human consumption. Alongside the bill, education is needed to emphasise that “if something is legal it does not mean it is safe”. Anything you consume is potentially unsafe, it is simply a matter of how much of it you consume.

Public opinion in Europe ranks information and prevention campaigns as the second most important way for the policymakers to tackle society’s drug problems. Second, that is, to punishing the drug dealers and traffickers, which this new bill will do.

The UK government has pledged to work with experts to develop a new drugs strategy but, as yet, there is no commitment to fund their information services (such as Talk to Frank and Alcohol and Drug Education and Prevention Information Service) or drugs education programmes at schools and universities.

Fortunately, this new bill will not criminalise people for possession of psychoactive substances (unless they’re already locked up). But surely educating people (particularly those in the most vulnerable, risk-taking 16-24 age group) about the various risks of psychoactive substances is key to preventing harm.

Prohibition coupled with easier global sales channels has fuelled the recent demand for legal alternatives. Surely further prohibition will only help reduce demand and, ultimately, harm if everyone is aware of the risks of using psychoactive substances. Only then can we make informed and educated choices about whether or not to use these substances, legal or not.