* Warning: This article contains graphic language that may upset some readers, while Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers should be aware that it may contain images, voices or names of deceased people.

With her first solo exhibition, artist Boneta-Marie Mabo has been inspired by the State Library of Queensland’s collections to create new works that speak back to colonial representations of Indigenous womanhood.

She found portraits of Indigenous women without any name, or with labels such as “black velvet” or “gin”; objects, rather than women. Men on the frontier sought to control Aboriginal lands as well as women’s bodies – with or without consent.

The 2005 documentary Pioneers of Love discusses the colonial fetish for Indigenous women.

Revered author Henry Lawson was one of the first to popularise the phrase ‘black velvet’. It described the soft, smooth skin of Aboriginal women – or ‘gins’, as they were referred to then. The men who associated with Aboriginal women were known as ‘gin jockeys’. And their children were often referred to as ‘burnt corks’. – Watch from 1:52 of this clip of the documentary.

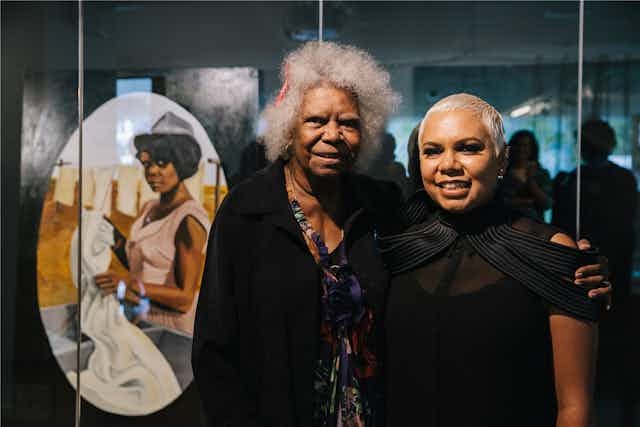

But Boneta-Marie’s exhibition, Black Velvet: your label, is more than a response to the past. It’s also about the struggle not to let others define our identity. And it’s a celebration of Indigenous women today, including Boneta-Marie’s grandmother, activist and Order of Australia winner Bonita Mabo.

Past and present inspiration

In 2015, Boneta-Marie Mabo was named as the inaugural artist-in-residence for the State Library of Queensland’s kuril dhagun Indigenous centre.

The year before, she won the People’s Choice award at the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Award for her street art-inspired works celebrating the life of her activist grandfather, the late Eddie Koiki Mabo.

Looking through the state library’s collections during her residency, Boneta-Marie says she felt “sad and really bothered” by the colonial portraits of Aboriginal women she discovered. Many had labels. But rarely were those ancestors referred to with any respect.

Black Velvet: your label responds to that history with nine life-sized works: five soft sculptures and four oil portraits with micro-story labels.

Boneta-Marie says her soft sculptures in black velvet were a way to “acknowledge all the women that are passed who didn’t have the ability to have control of their image or of their identity”.

The five black velvet soft sculptures encourage their viewers to contemplate the entrapment of being labelled by outsiders. Unseen hands push from behind the black velvet, never quite breaking through. These sculptures afford us a view of the resistance to labels.

Soft black velvet is used to resist the harsh label “black velvet”, which retains negative connotations for those who resist treating Indigenous women as sexual objects.

Portraits of women defining themselves

In contrast, Boneta-Marie’s oil portraits present four women of today as full and unique human beings.

They celebrate women at different stages of their lives, who chose their own poses and were labelled exactly as they wanted to be seen, including the youngster immersed in selfie culture, as well as a young mother feeding her baby.

Boneta-Marie’s smiling self-portrait sums up the sense of humour as well as history in this exhibition. The label beside it reads: “Boneta-Marie J Mabo (Neta-Rie), Piadram, Munbarra, Sugar slave descendant, an angry black woman and a lover of fashion and art.”

Boneta-Marie’s grandmother proved to be the most challenging portrait of all.

Now in her 70s, Bonita Mabo has lived an extraordinary life as an educator, mother of 10, and a tireless activist like her late husband.

But it took a while before old stories led them to the right moment in time to paint her: young, hard at work, and powerful.

* Black Velvet: your label is open to the public at the State Library of Queensland until May 29, 2016.