Breast cancer is the most common cause of cancer-related death in Australian women. But experts disagree on the benefits of breast cancer screening programs, with some arguing that it’s unclear whether it does more harm than good.

One in 11 women will be diagnosed with breast cancer before the age of 75. In Australia, as in many other developed countries, we have a screening program to detect breast cancer early because this offers the best chance of survival.

Early detection programs

The National Program for the Early Detection of Breast Cancer, now called BreastScreen Australia, was introduced in 1991.

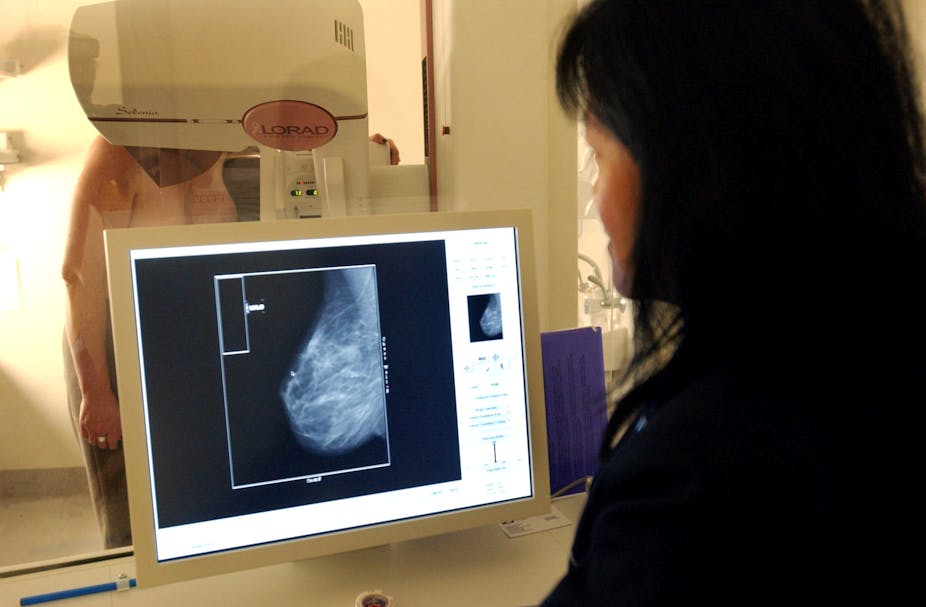

The program encourages all women aged between 50 and 69 years without any signs or symptoms to have screening mammograms every two years.

Mammography uses X-ray to try to find early breast cancers before a lump can be felt.

The reason for screening asymptomatic women is that early detection in this age group is believed to offer a better chance of successful treatment and recovery.

Researchers from the Nordic Cochrane Centre and others are now questioning this reasoning.

French researchers for instance, have recently analysed data from breast cancer deaths registered in the World Health Organization mortality database.

They compared three pairs of countries: Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, the Netherlands and Belgium, and Sweden and Norway.

The country pairs are neighbours and similar in population structure, socioeconomic circumstances, quality of health-care services and access to treatment.

But they differ in the length of time they’ve had mammography screening programs.

In one half of each pair, the program has existed since around 1990, while the other country introduced it some years later.

The researchers found that between 1989 and 2006, trends in breast cancer mortality rates varied little between the pairs of countries.

They concluded that screening didn’t play a direct part in the reduction of breast cancer mortality.

How can this be explained, if early detection is supposed to lead to better detection, treatment and years of survival after diagnosis?

Well, some of the cancerous tumours detected through screening grow very slowly, or not at all. Indeed, some disappear if left untreated.

So some women receive a cancer diagnosis even though their tumours won’t necessarily lead to sickness or death.

These women experience needless anxiety and stress and are treated unnecessarily.

A systematic review of interventions published in the Cochrane Library found that for every 2,000 women screened regularly for 10 years, one will avoid dying from breast cancer and have her life prolonged.

In addition, 10 healthy women, who wouldn’t have been diagnosed if they hadn’t participated in the screening program, will be diagnosed with breast cancer and treated unnecessarily.

These women have either a part or the whole of their breast removed, as well as often receiving radiotherapy and chemotherapy.

So why do it?

Unfortunately, medical science hasn’t yet discovered how to distinguish tumours that will lead to cancer from those that will disappear without treatment or cause no harm during the lifetime of a person.

But this isn’t explained to women when they are about to participate in breast cancer screening. The website of the BreastScreen Australia Program notes a 25% fall in mortality since the introduction of mammography screening, but doesn’t mention the unnecessary pain and anguish that may be caused by the program.

Instead, a link to a National Breast and Ovarian Cancer Centre position statement on over-diagnosis from mammography screening is provided. It is a technical statement and “not intended to be a decision-making aid for women considering screening”.

Women need to be given the existing evidence about benefits and harms of screening programs in a plain English statement and the opportunity to discuss the available evidence with their health-care provider. It is a necessary condition for informed consent.

After all, we expect to be provided with information about possible side effects of medical procedures and prescription drugs. So possible harms of screening procedures need to be disclosed as well.

The Nordic Cochrane Centre has developed a mammography screening leaflet that addresses the following questions:

What are the benefits and harms of attending a screening program?

How many will benefit from being screened, and how many will be harmed?

What is the scientific evidence for this?

The leaflet is available online in English and 12 other languages. BreastScreen Australia Program should either promote the use of this leaflet or develop its own.

Different people make different choices. Given all the information, some women may decide it’s reasonable for them to attend breast cancer screening with mammography.

Others may choose not to attend but all women need to know all the available facts to make an informed choice.