It’s been 23 years since Brett Whiteley’s death in Room 4 at the Beach Motel Thirroul, north of Wollongong. Larger than life during his 53 years, Whiteley remains embedded in our consciousness. Whether it’s an exposé biography, a record price at auction or a parsimonious review, he still commands headlines because the Whiteley name conjures up a world of glamour, money, sex and drugs.

His rock-star status and his popularity in secondary school art rooms may have eroded his street cred in the art world, but Lou Klepac’s book Brett Whiteley Drawings, published last year, and Ashleigh Wilson’s approved biography — waiting in the publishing wings — will no doubt re-energise the debate about his contribution to Australian art.

Klepac knew Whiteley well and worked with him while he was curator at the Art Gallery of Western Australia – dealing with the sensitivities over the acquisition of the artist’s major work of the sixties The American Dream – and later as a publisher.

This familiarity is manifest in the careful selection of the works, in the author’s sympathetic analysis of the chosen drawings and through his judgment of their significance in the artist’s oeuvre. His premise is straightforward: that Whiteley was essentially a draughtsman and drawing is at the core of his work as a painter, printmaker and sculptor. It is a thesis he succinctly articulates in his essay and illustrates well with a portfolio of reproductions.

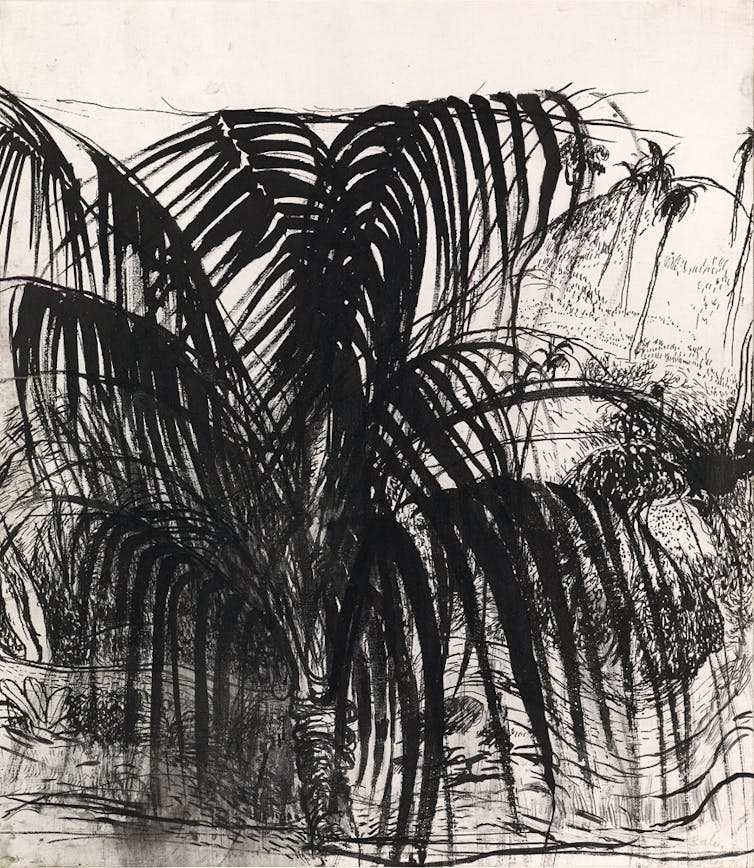

Whiteley was precocious – he won his first art prize aged seven — and from the early drawings of Sydney he made in his teens there is evidence of a strong graphic ability and considerable technical bravura. He drew incessantly. In his notes to a young painter the mature Whiteley described the process of becoming an artist:

If you want to be an artist go to an art supply house and get some ink and some paper and pens and a calligraphy brush and charcoal and aim at virtually whatever is in front of you. The subject matter is not that important. And then try and cheat and deceive and lie and exaggerate and most particularly distort as absolutely – as extremely as you can. And after some six months or a year, usually in a state of intense frustration, you’ll see something that you truly have never seen before. That is the beginning of yourself, and that heralds the beginning of different pleasure.

While many young artists take a great deal longer to achieve that goal, in Whiteley’s case it really was only six months to a year before he saw something he had never seen before. What is remarkable about his development as an artist is his confidence and ambition, which transformed him into a master of line, mass, shape and in particular pictorial tension in such a short period. Within two years of those early Sali Herman and Russell Drysdale inspired drawings, he was in Europe creating sophisticated works that would lead to further prizes and acquisitions by major museums.

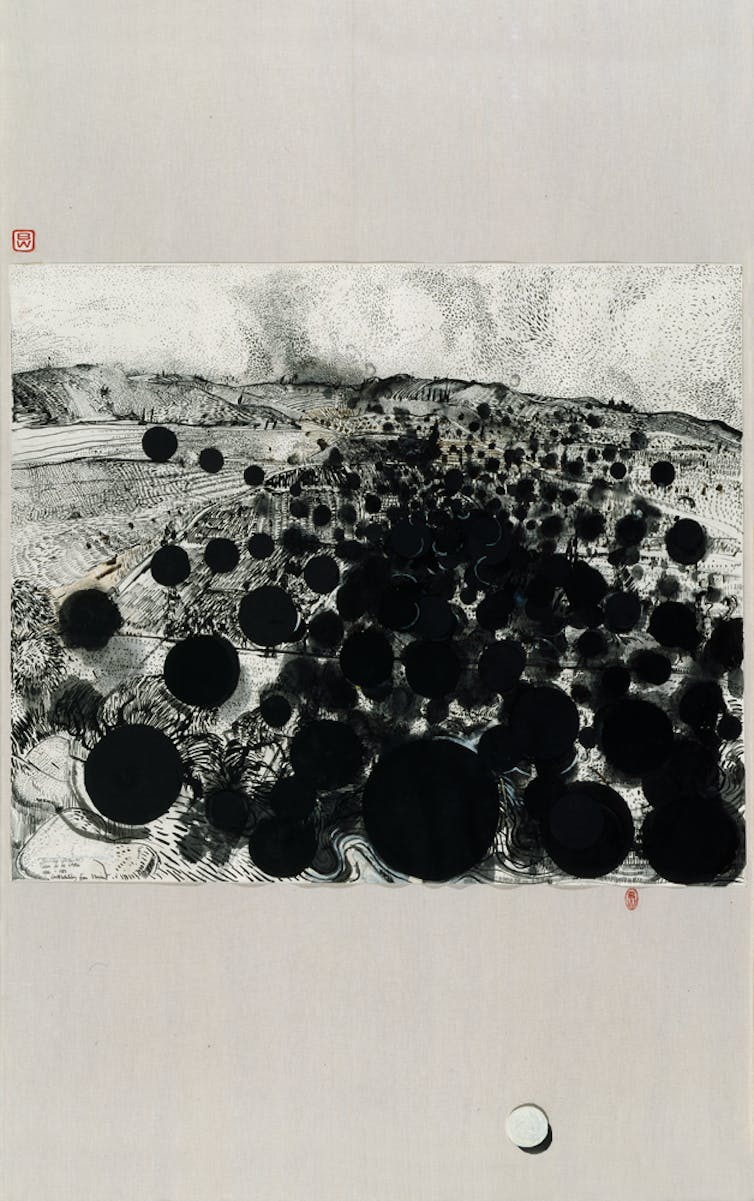

The Segean Drawings, created on his honeymoon in 1960, depict a landscape writhing with energy and ballooning out with fecund intensity. Through cheating, deceiving, lying, exaggerating and distorting as extremely as he could he transmuted the topography, roads, bridges and trees of the French countryside into a dynamic field in which each element is jostling for space and every edge is under intense pressure. The forms of the landscape are reduced to organic volumes that conjure up the memory of the terrain before it morphs into something new.

Almost seduced by the lure of abstraction, the impact of Francis Bacon’s work following his arrival in London sent Whiteley back to figuration and led to some of his greatest drawings. The Christie Series are an extraordinary achievement for a young man of 25.

Ever the perceptive critic of his own work Whiteley’s comment about his practice is particularly revealing. In his notes for the catalogue of an exhibition at Robin Gibson Gallery in 1985 he explained:

Some drawings are made in order for me to see something, some are made in order for me to show off. The best of my drawing, I feel, has been made either in acute self-consciousness or in complete unconsciousness with no middle-ground.

In his oeuvre there are a considerable number of “show off” drawings, some excellent “learning to see drawings” and in The Christie Series, some masterpieces where the artist was pushing at the extremes of his knowledge and his abilities.

The frenetic tumble of figures, the restraining chair, Christie’s makeshift gas mask and Kathleen Maloney’s tangled body pinioned by the stained presence of Christie himself, command our attention and draw us into the detail of the vicious deeds depicted. Only just contained by the edge of the paper the action swells to fill all the available space. The physical and emotional pressure of these scenes is overwhelming.

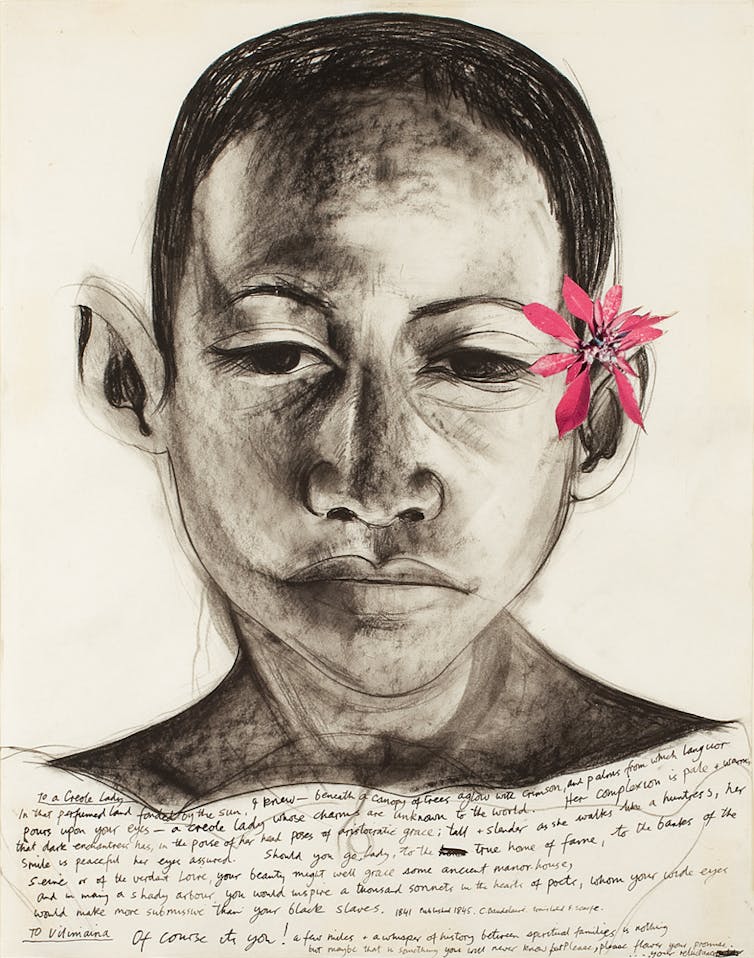

The rest of the book takes up the theme of “learning to see” with some wonderful landscape and portrait drawings, a fair smattering of showing off drawings and a group of remarkable works that seem to reframe the world in ways that are full of both anxiety and insight.

His search for states of complete unconsciousness ultimately led to his demise but in the process he did create some memorable images.

As a body of work, it reaffirms the book’s thesis that Whiteley was a draughtsman of extraordinary ability whose vision continues to have resonance and will likely remain a defining representation of late 20th-century Australia.