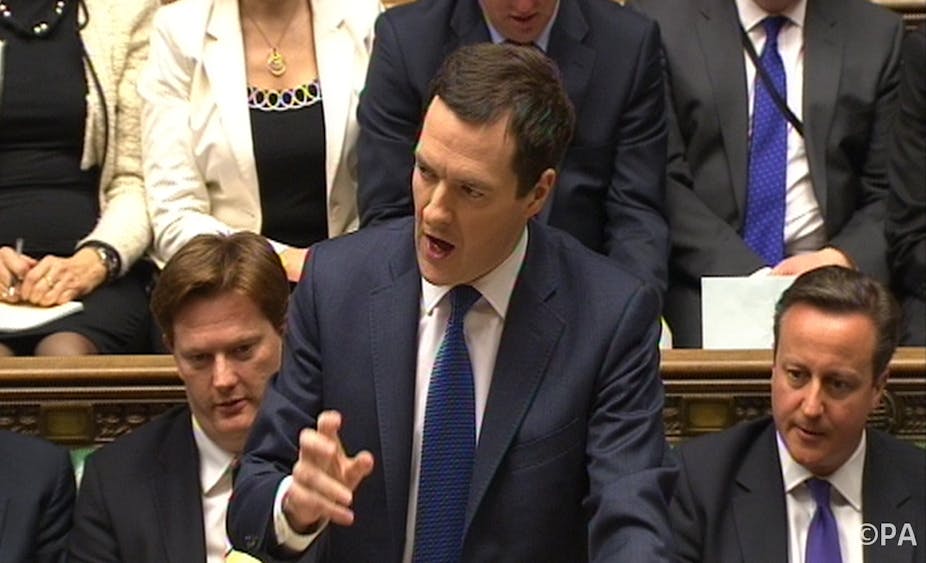

If Cameron is the heir to Blair, Osborne is the heir to Brown. His budgets have always been intensely political. The serious fiscal work now goes on in the spending review and the autumn statement. Budgets have become rather meaningless, but they still give the opportunity to send political messages to particular groups of voters as well as to reinforce the central narrative of what the government is trying to achieve.

The 2014 budget, like its predecessors, was filled with endless tinkering with tax rates and tax allowances. There were few big announcements, which was probably deliberate. Budgets sometimes unravel after they have been delivered, as the 2012 budget did most spectacularly, being remembered as the “Omnishambles Budget”.

It was important that this budget, just one year before the general election, should not backfire in this way. Osborne wanted to deliver three main messages. The first is that his fiscal plan, first laid out in the emergency budget of June 2010 and in the autumn statement of that year, is working.

The deficit is coming down and the plan now is to eliminate it altogether in 2018, debt will peak in 2016 at 78% per cent of GDP and then start falling, and growth is predicted to be around 2.5% per annum for the next few years.

But Osborne stressed throughout his speech that these targets will only be achieved if his fiscal plan is followed through, which means continuing pay restraint and spending cuts; in other words, continuing austerity, at least as far as the public sector and local government are concerned. This meant that there could be no big give-aways before the election, he said – before going on to announce some.

His second message was that the government wanted to support the recovery by assisting the rebalancing of the economy towards industry and exports and away from finance. There were a number of measures providing incentives to manufacturers to invest more, as well as reducing energy bills. The coalition has been criticised in the past for being too focused on the deficit and neglecting growth. Osborne tried to make amends by talking up the prospects of British industry and predicting an industrial renaissance. “Things are looking up” is seen as a big vote-winner.

His third message was that the government is “on your side”, directed to specific groups of voters the government needs to persuade or hold at the next election. Some of these, like the 1p reduction on a pint of beer and the halving of tax on bingo, were designed for the tabloids. The two more serious measures were tax relief on the costs of child care for working parents and the package of measures for savers and pensioners. The Liberal Democrats were given ownership of the first, in return for the Conservatives being given ownership of the second.

The five-year test

Will any of this have an impact on voting, or will this budget like so many in the past barely be noticed? The opinion polls remain stuck, with very little recent movement. The Conservatives face two major problems. The first is that living standards for most voters will be lower in 2015 than they were in 2010. The second is UKIP – the first time that the Conservatives may have to fight an election with a serious challenger on their right.

In his Mais lecture just before the 2010 election George Osborne said that when people ask the famous question: are you better off than you were five years ago, this will be the first election in modern British history when the answer from the government must be no. His problem is that 2015 will be the second.

This is why he continues to rely so heavily on the argument that the financial crash and recession were entirely Labour’s fault, the result of a decade of debt, and that only the Conservatives can be trusted to build a resilient economy.

Over the last four years Osborne has been forced to revise his forecasts several times and has failed to deliver on his central promises on the debt (which is still rising) and on the deficit and borrowing (which he promised in 2010 to eliminate in the space of one parliament). But none of that matters so long as most voters trust the Conservatives more than Labour to manage the economy.

The pitch to the electorate is: we held our nerve, but the job is not done. Osborne hopes that this central message, combined with even a small rise in living standards between now and the time of the next election, coupled with some of the specific help on child care and savings, will persuade enough voters, particularly those tempted to desert to UKIP, that the economy is at last improving and the Conservatives deserve their vote.