By cutting through the buzz and spin surrounding the federal budget, The Conversation’s budget explainers arm you with the key terms and facts needed to understand the budget and what it means for you.

A budget deficit is the difference between revenues and expenditures. Revenues come mainly from taxes while expenditures include interest payments and government spending on areas such as education, health, welfare, and defence.

Figure 1 shows how government receipts and payments, expressed as a percentage of nominal gross domestic product (GDP), have changed since the early 1990s. Total revenue fell during the global financial crisis (GFC) and is currently languishing at 23% while total expenditure rose during the GFC and is still at a high of 26%.

Why a structural deficit is more concerning than a cyclical deficit

What is concerning is that the budget deficit may get worse. This is because the problem with current revenues and expenditures is partly structural not just cyclical.

In general, budget balances are cyclical. Surpluses tend to occur during times of strong GDP growth when tax receipts are up and welfare spending is down. Deficits tend to occur and rise during times of economic slowdown, driven by a combination of declining tax revenues and rising welfare expenditure. It follows that a cyclical deficit will normally improve with economic growth.

In contrast, fiscal imbalances that are structural are caused by fundamental changes in the economy, and growth will not necessarily improve the deficit.

The classic example is expenditure on health – this is mainly structural as it is driven by an ageing population, and expenditure on age-related health issues will grow irrespective of the state of the economy.

Of course, structural and cyclical imbalances are not completely independent, as a prosperous economy is better equipped to finance any type of expenditure.

Unfortunately, splitting the budget deficit into its structural and cyclical components is not straightforward. Taxes and expenditures have elements of both, although they may be predominantly one type or other.

For example, tax revenues are mainly cyclical, rising and falling with changes in national income. However, a structural change in the economy can permanently change the source of income, as evidenced by the drop in the terms of trade and the commensurate (and permanent) drop in royalties associated with the mining sector.

The Australian Treasury itself has explained why determining the structural budget balance is so difficult and why their estimates differ from those proposed by the International Monetary Fund and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Deconstructing the budget

We can deconstruct the budget deficit roughly into its structural and cyclical parts by determining the share of revenue and expenditure that moves with nominal income. Intuitively, one estimates how much of the growth in total revenues and total expenditures is associated with the growth in nominal GDP and attributes the remainder to other factors such as discretionary policies and/or unexplained events.

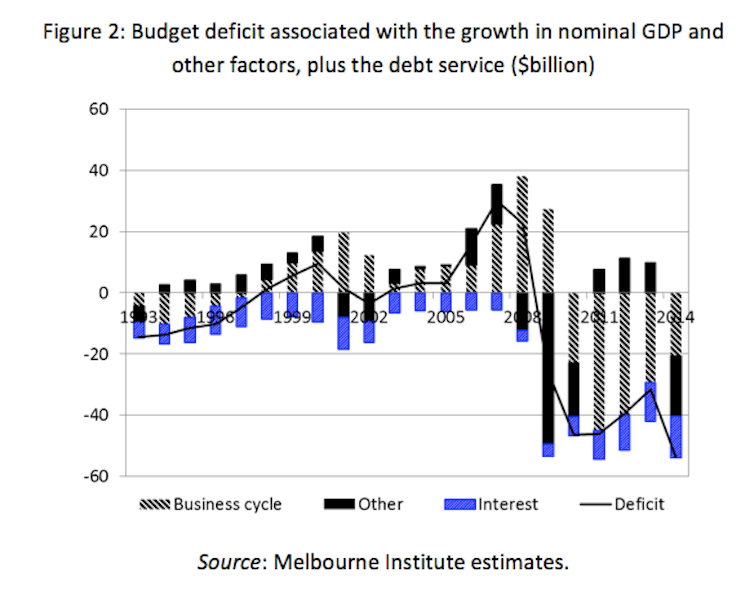

Figure 2 illustrates the various components of the budget deficit. For convenience and to be pedantic about the use of the words “structural/cyclical”, the part which moves with nominal GDP is labelled as the “business cycle” component and the remainder is called the “other” component.

The “business cycle” part takes into account the boom effects of improvements in the terms of trade, slow growth and the GFC.

The “other” part is mainly due to the discretionary actions by governments to unexpected events like natural disasters and includes the stimulus packages during the GFC.

Figure 2 shows the 2014 budget deficit is split roughly between interest payments, business cycle effects and “other”.

The business cycle component is not small. It reflects the impact of slow growth but this estimated cyclical deficit gap will decrease with economic growth.

The service of government debt (the interest payments component) is not an immediate problem as interest rates are low. However, debt servicing will be a problem if, and when, interest payments accumulate to the point when they cannot be paid on a regular basis.

The “other” budget component illustrates the role played by changes in tax and expenditure policies. This estimate gives a very rough indication of the degree of fiscal consolidation needed to close the structural deficit gap.

Policy Responses

Understanding whether the fiscal balance is driven by cyclical or structural factors is important for informed policy discussion.

If the fiscal imbalances reflect normal and temporary changes to the state of the economy, then policy is better directed at smoothing deficits and surpluses. However, if the fiscal imbalances reflect fundamental (permanent) changes in the economy, then policy should be directed at altering the receipts and payments (ie changing taxes and expenditures). The former is more about growth stabilisation policies while the latter is more about fiscal policies.

The challenge is to identify the nature of the budget deficit problem (structural or cyclical), and to devise appropriate policy responses.

Read more Budget Explainers here.

Or interested in further budget coverage? Read more in our two series: Economy in Transition and Australia’s Five Pillar Economy.