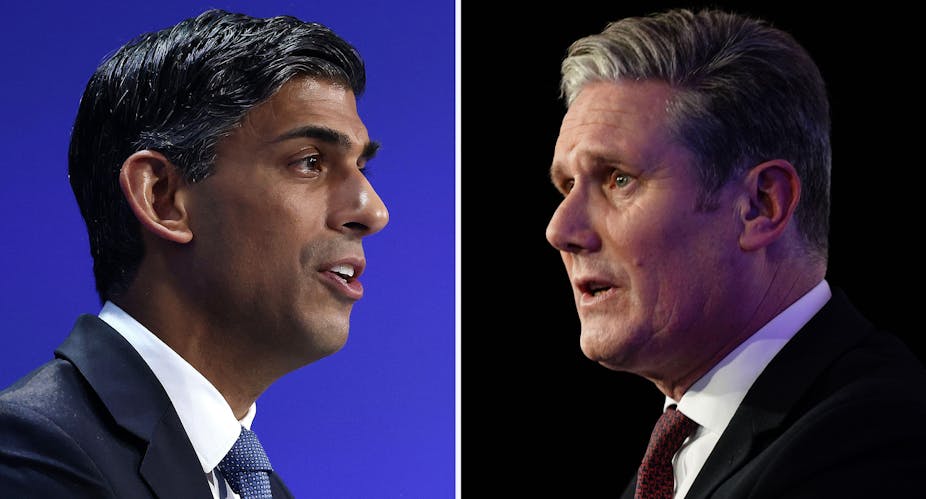

Rishi Sunak paid over £500,000 in UK taxes last year, recent documents published by the government revealed. As well as displaying a considerable contribution to the nation’s coffers, the details of the prime minister’s financial affairs also highlighted a common perk enjoyed by many wealthy British citizens who have substantial investments: that their tax bill is a fraction of what it would be if they received all of their money as earnings from their day job.

For while the prime minister’s salary of just under £140,000 is subject to income tax, Sunak also received nearly £1.8 million from his stake in a US-based investment fund. This “capital gain” was taxed at 20%, far below the 45% rate of income tax that Sunak would have paid if that sum had been treated as income in the UK tax system.

The leader of the opposition Keir Starmer also benefited from low capital gains tax rates. Two thirds of his £404,030 total remuneration in the last tax year came from the sale of a field, on which the appropriate capital gains tax was paid.

By taking all sources of income and capital gains together, both party leaders paid an effective tax rate of less than 25% on the money they made in 2023.

Some economists and politicians – both left and right – think capital gains and income should be taxed at the same rates. But this idea is often met with concern that such reform could prove costly for “ordinary” taxpayers.

Part of this worry seems to stem from a misconception about how capital gains tax is applied. And because the wealth of the British middle class is largely tied up in housing, some fear that homeowners selling their residence (when downsizing for retirement for example) will be hit by a sizeable tax bill.

But a taxpayer’s main residence is exempt from capital gains tax. It’s only the sale of second (or third or fourth) homes that is subject to capital gains.

Others worry that taxpayers might not have the cash to pay a tax bill without having to sell off their assets prematurely. But again, it is only on the sale of assets that capital gains tax is applied, so any increase in value that occurs while a taxpayer still holds an asset is not taxable until that point.

So how much impact would capital gains tax reform actually have? Our recent report draws on the anonymised tax records of all UK taxpayers from 1997 to 2020, to determine who exactly would be concerned by changes to this policy.

We found that very few British taxpayers need to concern themselves with capital gains tax at all. In fact, in 2020, only 0.5% of UK adults paid capital gains tax. Over the preceding decade as a whole, the proportion was 3%.

Capital gains are also extremely concentrated among the rich. Even restricting our focus to the fraction of the population who receive capital gains reveals striking levels of inequality. Over half of all taxable capital gains in 2020 went to the top 5,000 taxpayers – just 0.01% of UK adults – who each received an average gain of over £6.8 million.

Capital gains also tend to be received by taxpayers who already have high incomes. Roughly 43% of taxable gains went to people with at least £150,000 in annual income.

These results partly reflect substantial differences in the likelihood of receiving capital gains by income level. In a given year, almost 40% of taxpayers with incomes of at least £5 million paid capital gains tax, compared with just 0.3% of those with incomes under £50,000.

London, capital of capital

These patterns point to fundamental differences in the ways that rich taxpayers receive remuneration compared to the middle class. While capital gains hold relevance for only a small fraction of “ordinary” taxpayers, their importance as a source of remuneration is large – and growing – among higher earners.

We also noticed sizeable regional inequalities in capital gains throughout the UK, painting a stark contrast between southern parts of England and the rest of the country. While London accounts for roughly 13% of the total population, it is home to over a quarter of the UK’s taxable capital gains.

Even within London, gains are concentrated in affluent areas such as Kensington, Westminster and Hampstead, where average gains are hundreds of times higher than in other parts of the city.

So the finances of both Sunak and Starmer reflect a broader pattern of how high earners in the UK derive far more benefit from low capital gains tax rates than “ordinary” taxpayers do. Those gains are collected by a small fraction of UK taxpayers, who are typically rich to begin with.

It is people fitting this profile – and not the vast majority of taxpayers – who would bear the brunt of any capital gains tax reform.