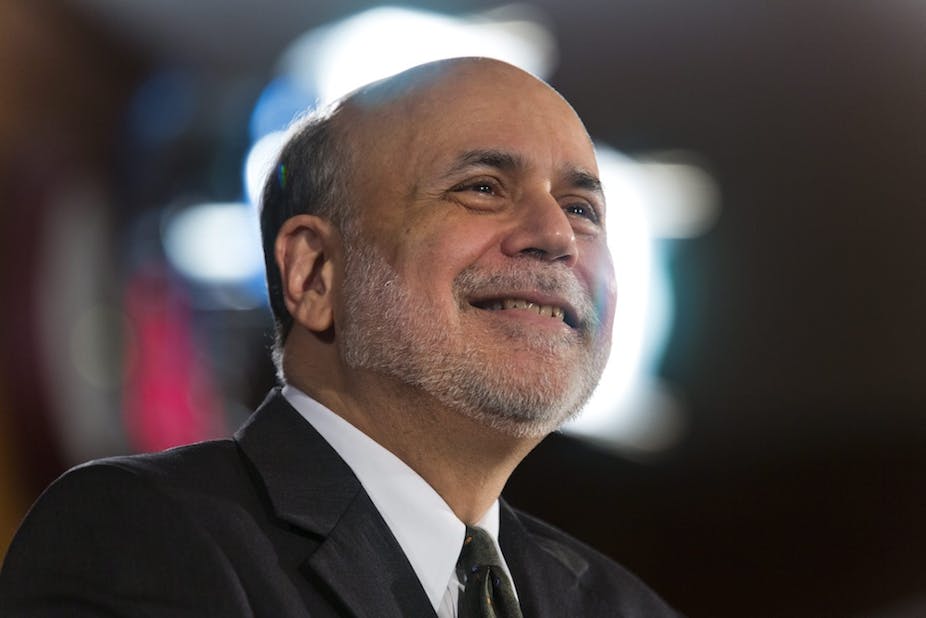

The mere suggestion that the United States might reduce its quantitative easing program sent global markets into a spin last week. Though Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke had said something similar before, his reiteration that the US Federal Reserve could scale back its $US85 billion-a-month bond-buying program later this year sent sharemarkets downwards and prompted a sell-off in bonds.

But, as markets stamp their feet, the question is: Has quantitative easing been distortionary? If central banks keep the cheap money rolling, are we trading away long-term, sustainable growth for the illusion of market efficiency?

Not surprising

The Federal Reserve is considering winding back its quantitative easing program because it believes US economic growth is gaining momentum. A reduction of this program, which focuses on the purchase of US treasuries and mortgage-backed securities, will mean a reduction in bank liquidity, leading to lower lending volumes and higher interest rates.

The quantitative easing programs in the United States, the United Kingdom and most recently Japan have been controversial among economists. Japan followed such policies in the early 2000s but was still unable to recover from recession lasting more than 20 years.

In addition, the fear exists (rightly or wrongly) that these programs will increase inflation. While this would benefit big borrowers – first and foremost countries such as the US, Europe and Japan – by reducing their debt in real terms, it would penalise net savers, such as age pensioners, by eroding the benefits they’ve worked to accrue.

The immediate impact of a reduction in quantitative easing is an increase in medium and long-term interest rates, as demand for US treasuries declines. Yields on such treasuries, as well as other interest-rate sensitive products – including 30-year, fixed-rate mortgages in the US – have increased in recent weeks by as much as 1%.

A potential severe impact could be on the US federal budget and the country’s sovereign risk as the coupons on treasury securities increase, making it even harder for the US to remain within its debt targets – raising the Europe-style spectre of further political stand-offs, funding cuts and public sector job losses.

So, it’s not surprising that global financial markets quickly responded with falling prices for equities and commodities and, in Australia, the value of our dollar.

The trade-off

The various quantitative easing programs were originally intended for the short term, in particular to overcome market deficiencies such as credit and liquidity crunches. However, as time has passed markets have become reliant on governmental support.

Financial crises are recurring events and often reflect the need for change. Are we procrastinating over necessary change by such interventions? Would we be better off limiting these efforts to a bare minimum?

The markets remain uncertain about the future despite unprecedented economic stimulus efforts since the advent of the global financial crisis in 2007-08. Many long-term industry projects in Australia and overseas that promised to create jobs and wealth have been put on hold, some even terminated, while others are at risk.

Meanwhile, these market impacts are exacerbated by ripple effects because of the way our belief in functioning and efficient markets underpins everything from market-value-based accounting to our superannuation system.

At times, an end with losses may be better than losses without an end.