Death is a funny thing. It creeps up on us all, or surprises us if we are unlucky (or lucky, depending on the circumstances). For a writer, especially a self-confessed solipsist such as Clive James, the impending end of creativity brings with it a fresh awareness of the self, and a new personal experience to interpret for others.

Born in the year the second world war began, James is now 74, and suffering from leukaemia and emphysema. Regular hospital visits keep him close to home in Cambridge, so his appearance at the Australia and New Zealand Festival of Literature & Arts at King’s College London last Saturday was a special occasion. It was with a sense of momentous anticipation and a touch of apprehension that a packed lecture hall awaited his appearance.

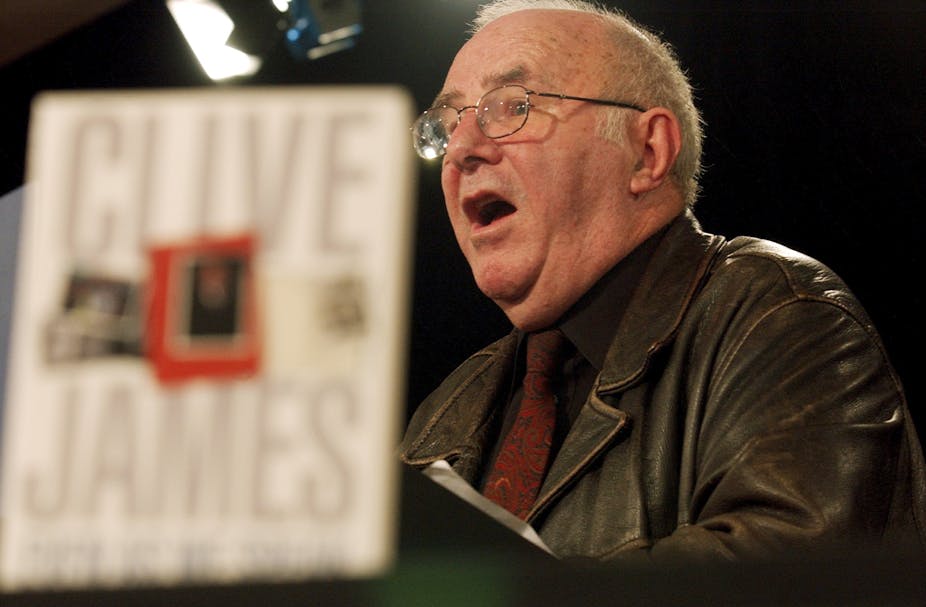

But James, when he shuffled onto the stage smiling, was in his element.

As earlier reviewers have noted, he settled into his chair and joked about “another farewell appearance”. So why had he decided to do it? With a rogue twinkle, he said, “Like every other red blooded Australian male, I’m doing it to impress Tony Abbott’s daughters”. The audience roared with laughter, and the one-man show that is Clive James began.

A London-based festival celebrating antipodean writers was a fitting event to choose for his final public hurrah. Since arriving in England from Sydney in 1961, Clive James has built a remarkably varied career as a literary and cultural critic, television personality, essayist, novelist and poet while always cherishing his Australian identity as “the kid from Kogaragh”.

His first reading of the afternoon, the poem In Town for the March, evoked his childhood memories of being taken to the Anzac Day parade in Sydney by his mother, watching the “marching men” go by: “even the men from the first world war, straight as a piece of two-by-four”. His own father had died in in an airplane crash in the second world war after surviving the Japanese POW camps.

James described his younger self as “an orphan standing with the widows, wearing my father’s medals”. Although it happened half a world away, James says that in his older age these Sydney memories are more vivid than ever.

It was an anonymous article James penned on Edmund Wilson for The Times Literary Supplement while studying at Pembroke College, Cambridge, which established his literary reputation in Britain. The essay later appeared in his first collection of literary criticism, where it also provided the title, The Metropolitan Critic (1974).

His oeuvre is now impressive, including five volumes of memoirs, seven collections of essays, five books of verse, and his most recent labour of love, a translation of Dante’s epic poem The Divine Comedy, which was nominated for the 2013 Costa Book Prize.

For most people, Clive James became a familiar name and face during the 1980s and 1990s, when he hosted a raft of television programs including Clive James on Television, Saturday Night Clive and Clive James Postcards From …, and later an eight-part BBC documentary, Fame in the 20th Century.

Name a celebrity and the odds are they’ve been interviewed by James – the fresh-faced Spice Girls appeared on his show in 1997, and the clip is worth a watch on YouTube, if only for the moment when Scary Spice threatens to give Clive a good spanking:

At the festival on Saturday, an audience member asked if James had any regrets about being better known for his television work than his poetry or writing. James quickly dismissed the quandary as “inevitable”. The size of the audience doesn’t determine the quality of the work, and besides, “television paid for the groceries, as a poet I would have starved”.

His ability to seamlessly interweave both “high” and “low” culture was, as ever, on display. Until recently, James told the rapt audience, he had been staunchly “anti-dragon” – scaly creatures were best left to mythology. He began watching season one of the HBO series Game of Thrones at the behest of family members, telling himself that once the dragon eggs hatched, he’d switch it off. But now, having devoured the following two seasons, he has become a convert.

From jokes about the lead characters (“the blonde who has a lot of trouble keeping her clothes on”) and on staying alive until the release of season four as a box-set (“one of my ambitions at this age and in this condition”), we were introduced to the “poet’s poet”, U.A. Fanthorpe, and her poem Not My Best Side, inspired by Uccello’s 15th-century painting St George and the Dragon.

Fanthorpe gave a voice to each character in the painting – the dragon, the princess, and George, but it was the princess’s voice that James read, revelling in another poet’s words and humour (the princess resigns herself to life with George: “the dragon got himself beaten by the boy, and a girl’s got to think of her future.”). And from there another fire-breathing leap to his translation of The Divine Comedy, and the passage in which Virgil takes Dante on a ride into the depths of hell on Geryon, a dragon with a man’s face.

There is no doubt that Clive James is a master storyteller, but what amazes in person is the joy he takes in finding the connections between different forms of human expression, from television, to art, to poetry and film. Since my own Game of Thrones conversion last year, I’ve heard and read countless conversations and commentaries about the show, but none as engaging, wide-reaching and down-right hilarious as his.

So how does coming face to face with the end change a writer’s work? For James, the reasons for putting pen to paper haven’t changed – he does it because he has to, because he couldn’t do anything else, because it’s a “way of belonging”.

And the project of “trying to complete yourself on the page” still continues (he threatens a sixth volume of memoir, titled The Run to the Judge, words used by the legendary race-caller Ken “Magic Eye” Howard at the end of many a horse race).

His last reading on Saturday was poem written only a month ago, Sentenced to Life, about “what it’s like to be on the home stretch and still wanting to write something”.

Deeply moving in its simplicity and sincerity, the poem is laced with his characteristic self-deprecating wit and an enchantment with the smallest of life’s pleasures. Ending the talk on such a note could easily have slipped into mawkishness, if it weren’t for James’ reassurance that he wasn’t really leaving, and would instead be reappearing upstairs shortly, for – you guessed it – a book signing.

By the time I left the venue more than an hour later, the festival bookshop was almost sold out of Clive James titles, the queue was still a mile long, and Clive James was still doing what he loves most – meeting his readers.