Richard III’s skeleton, dug up from a carpark in Leicester in 2012, is currently the subject of a legal dispute about where he should be buried.

In one corner is the University of Leicester, whose archaeologists dug up and identified the skeleton. The university was given a licence by the Justice Ministry to exhume Richard and to appropriately dispose of his remains.

University archaeologists assumed the proper site for burial was Leicester Cathedral, and work on the crypt to house the body was supposed to be completed this year.

In the other corner is the Plantagenet Alliance Limited – a recently formed group of distant relations of Richard who claim that failure to take into account relatives’ wishes and Richard’s preferences is a serious violation of human rights.

The Plantagenet Alliance think Richard would have preferred York as a burial place because he grew up nearby and was strongly supported by people of that city.

The British High Court adjourned the case at the end of last year when the City of Leicester, the owner of the carpark, became one of the parties to the dispute.

Richard will be a lucrative tourist attraction for the city and cathedral that houses his bones.

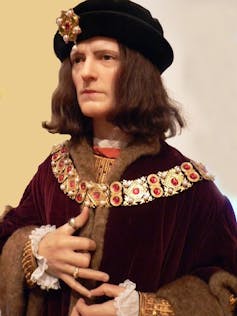

Richard III was killed 530 years ago in the Battle of Bosworth Field. His death ended the Plantagenet line of kings. He was succeeded by the first Tudor monarch, Henry VII.

The search for Richard’s remains was financed by the Richard III Society, a group dedicated to rehabilitating Richard’s reputation. He comes down in history as he is portrayed by Shakespeare – a villain who murdered his nephews in order to become king.

The legal dispute over his bones arises from moral and legal considerations that archaeologists and their sponsors are supposed to take into account. In making decisions about how human remains should be treated, they are not the only ones whose opinions count.

Descendants or those whose traditions or religious beliefs give them a special relation to the deceased have a right to be consulted. In Australia, archaeologists are expected to consult with Aboriginal communities when they uncover ancient bones on Aboriginal land.

However, the belief of the Plantagenet Alliance that it has a right to determine Richard’s burial place rests on morally dubious grounds. Relatives generally do have rights in such matters. But this is because they have a personal relation to the deceased or because they share the same traditions. Members of the Plantagenet Alliance merely have a remote genetic connection.

What Richard would have wanted is an unanswerable question. If finding out what the dead would prefer is a matter of knowing what they wanted when they were alive, then for Richard this is unknowable and anyway not relevant in a world very different from the one he experienced. If finding out what the dead would have wanted is a matter of imagining how they would respond if they could be updated on events after their death, the answer is undeterminable.

Members of the Plantagenet Alliance have no ability or entitlement to answer this question of where Richard should be buried. But neither do archaeologists or the City of Leicester.

So who should determine what happens to Richard’s remains? The obvious answer is that the decision should be made by those who can speak for the country that Richard once ruled. This authority now rests with citizens rather than a monarch.

The country Richard ruled was very different from the one that exists today - in geography as well as customs and institutions – but this does not mean there is no relevant connection between past and present. Heritage passed down through the generations is an important aspect of a nation’s identity. Public interest in Richard’s exhumation is a good indication of the value to people of a connection with history.

That and the dispute about Richard’s bones show that decisions about heritage should not be made by governmental fiat or by a small group of experts. An ethical and politically satisfactory solution would be for disputants to allow the question of Richard’s burial place to be decided by an independent panel on the basis of submissions by interested people and opinion polls.

There is a precedent. In 2006 the Orders of British Druids requested that neolithic skeletons be reburied rather than displayed in a museum. English Heritage and the National Trust made a decision (in favour of the museum) on the basis of public consultation and an opinion poll.

The Plantagenet Alliance has questionable ideas about how the case should be determined. It will be no violation of human rights if Richard ends up in Leicester Cathedral. But the Alliance has performed a useful service by insisting that he cannot be buried without consulting those who have an interest.