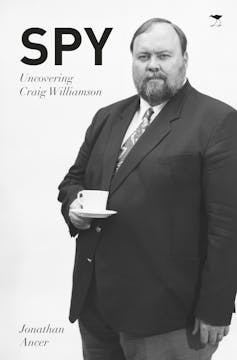

-Book Review: Spy - Uncovering Craig Williamson by Jonathan Ancer; Jacana Media, Johannesburg, March 2017

One can judge a book’s bleakness by the photograph on its cover. The Mephistophelian figure holding a tea cup is Craig Williamson: police informant, Cold War spy and apartheid assassin.

Prizewinning journalist Jonathan Ancer’s goal is clear from the get-go. He wants to expose the man on the cover in all his infamy in order to set himself free.

It’s no surprise, then, that there’s no place in these pages for the political philosopher Hannah Arendt’s idea of the “banality of evil” – those who perpetuate terrible deeds are mostly thoughtless functionaries.

For Ancer the man on the cover of the book – not apartheid, nor his handlers – was responsible for a two-decade career of falsehood, cover-up, betrayal, and murder. These were Williamson’s choice, and his alone.

Class, rather than race at the core

So who is (or was) Williamson?

Born into an English-speaking Johannesburg family, Williamson was schooled at one of the city’s great institutions, St John’s College. Gently, Ancer opens to the idea that class, rather than race, may have been at the core of Williamson’s inability to tell right from wrong.

Awkward and always overweight, the boy was bullied and in turn learned to bully. Other writers might have been tempted to position a propensity for violence at the centre of their narrative. Ancer is near playful when discussing Williamson’s school days.

But trawling through old copies of the school magazine, Ancer discovers that when they emerged, Williamson’s politics were of a raw racist strain which was integral to the search for a white South African patriotism after the Second World War.

In 1966, Williamson won a school debating-cum-mock election by drawing on the racial ideology espoused by the (now long-forgotten) Republican Party, a right wing splinter group of the National Party.

If this was the direction of his politics, his “gap year” confirmed it: his national served was not with apartheid’s South African Defence Force (SADF), as was the case for most young white men, but with the South African Police (SAP).

It was 1968. Maintaining domestic order and the travails of white-ruled Rhodesia, were uppermost in the thinking of prime minister John Vorster, apartheid architect Hendrik Verwoerd’s successor. Their National Party embarked on a charm offensive towards English-speakers: an approach that drew on the pervasive anti-Communism of the time.

So, young Williamson’s choice of national service in the SAP – which was then at the sharp end of racial repression – didn’t seemed untoward, even in Johannesburg’s supposed more liberal white English-speaking northern suburbs.

Student politics

After his year in the SAP, he enrolled to read Politics and Law at the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits). Here Williamson began his decade-long career of subterfuge. He immersed himself in student politics: first, through the Wits Students’ Representative Council (SRC) and, later, the leftist National Union of South African Students (Nusas).

During these years, Williamson interacted with (and reported on) several generations of student leaders from almost every English-speaking university. Interviewed by Ancer, several of them report that suspicions about Williamson abounded, but the liberal impulse to believe, to forgive, to understand, stayed any serious investigations of a double life.

After Nusas, and purportedly without a passport, Williamson was catapulted (accompanied by his medical student wife, Ingrid) into the Geneva-based International University Exchange Fund (IUEF). This Nordic-funded body fronted for liberation movements across the world, but particularly in southern Africa.

This was when the police informant turned to espionage by passing information to apartheid’s notorious Special Branch (SB). Despite Williamson’s hints to the contrary, there’s no hard evidence that he passed on deep Cold War secrets to western intelligence agencies.

But, here, regretfully, Ancer leaves an intriguing question hanging. Might Williamson not have been working for the British, too?

This question isn’t asked out of mischief or malice. It simply connects the dots. Williamson’s Scottish-born father, Herbert, had a claim on British citizenship. If these were exercised the son might have travelled under the cover of British papers; and maybe he even worked as a double agent.

Imperfect infiltrator

In Geneva the ever-dutiful, ever-practical Williamson was drawn into the IUEF, eventually becoming deputy to its Swedish Director, Lars-Gunner Erikson.

But efforts to infiltrate (and divide) the ANC and the PAC in London were imperfect; indeed, these may well have been the moment every spy fears, overreach. His undoing came in an exposé in the British press after the defection of a South African agent.

He immediately absented himself from the IUEF and called his SB handler, General Johann Coetzee, who flew to Europe to accompany Williamson (and Ingrid) back to South Africa.

On landing, he was lauded by the local press – especially the then odious Sunday Times – who played off the metaphors of the Cold War spy-writer, John le Carré. It’s not surprising that in apartheid circles he became something of a hero. But an exaggerated James Bond-like characterisation of himself rendered him a figure of fun, even within the Security Branch.

Williamson continued to work in apartheid’s cause: building its international work, serving on various security bodies, and participating in South Africa’s wicked policy of regional destabilisation. It was in servicing the latter that the Cold War spy turned into an apartheid assassin.

Personal anguish

If Ancer is measured in the early part of the narrative, he draws from the depth of his craft – and his personal anguish - to describe Williamson’s role in the assassinations of three people. Journalist, academic and political activist, Ruth First, was killed by a parcel bomb in her office in Maputo, Mozambique. Fellow anti-apartheid activist, Jeanette Schoon, and her six-year old daughter, Katryn, suffered the same fate in Lubango in Angola.

For these killings and the bombing of the ANC Office in London, Williamson appeared before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s (TRC) Amnesty Committee in September 1998. He was, according to an eyewitness, “not even remotely apologetic” for his role in these atrocities. But within the legal technology of the TRC process, Williamson’s 21-day performance was sufficient enough to be granted the amnesty he sought.

But what incenses Ancer – and should incense us all – is that the man on the cover’s sole interest was in reproducing what he regarded as his birthright: wealth and racial privilege. This is a beautifully written and meticulously researched book; it’s story told with disarming intellectual honesty and great passion. It’s destined become a minor classic about apartheid’s ruinous path.