As an anthropologist, I know that all groups of people use informal practices of social control in day-to-day interactions. Controlling disruptive behavior is necessary for maintaining social order, but the forms of control vary.

How will President Donald Trump control behavior he finds disruptive?

The question came to me when Trump called the investigation of Russian interference in the election “a total witch hunt.” More on that later.

Ridicule and shunning

A common form of social control is ridicule. The disruptive person is ridiculed for his or her behavior, and ridicule is often enough to make the disruptive behavior stop.

Another common form of social control is shunning, or segregating a disruptive individual from society. With the individual pushed out of social interactions – by sitting in a timeout, for example – his or her behavior can no longer cause trouble.

Ridicule, shunning and other informal practices of social control usually work well to control disruptive behavior, and we see examples every day in the office, on the playground and even in the White House.

Controlling the critics

Donald Trump routinely uses ridicule and shunning to control what he sees as disruptive behavior. The most obvious examples are aimed at the press. For example, he refers to The New York Times as “failing” as a way of demeaning its employees. He infamously mocked a disabled reporter who critiqued him.

On the other side, the press has also used ridicule, calling the president incompetent, mentally ill and even making fun of the size of his hands.

Trump has shunned the press as well, pulling press credentials from news agencies that critique him. Press Secretary Sean Spicer used shunning against a group of reporters critical of the administration by blocking them from attending his daily briefing. And Secretary of State Rex Tillerson shook off the State Department press corps and headed off to Asia with just one reporter invited along.

Again, the practice cuts both ways. The media has also started asking themselves if they should shun Trump’s surrogates – such as Kellyanne Connway – in interviews or refuse to send staff reporters to the White House briefing room.

Accusations of witchcraft

But what happens when informal means of control don’t work?

Societies with weak or nonexistent judicial systems may control persistent disruptive behavior by accusing the disruptive person of being a witch.

In an anthropological sense, witches are people who cannot control their evil behavior – it is a part of their being. A witch’s very thoughts compel supernatural powers to cause social disruption. If a witch gets angry, jealous or envious, the supernatural may take action, whether the witch wants it to or not. In other words: Witches are disruptive by their very presence.

When people are threatened with an accusation of witchcraft, they will generally heed the warning to curb their behavior. Those who don’t are often those who are already marginalized. Their behavior – perhaps caused by mental disease or injury – is something they cannot easily control. By failing to prove they aren’t a “witch” – something that’s not easy to do – they give society a legitimate reason to get rid of them.

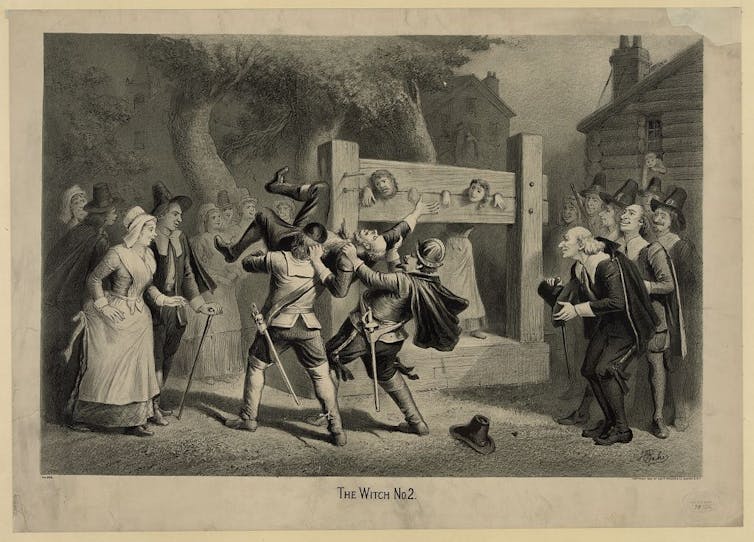

When communities and their leaders turn to accusation of witchcraft as a means of social control, it usually leads to executions. From the 15th to the 17th century, as many as 100,000 accused witches were put to death in Europe. And in Salem, Massachusetts, 20 people were executed during the notorious witch trials of 1692 and 1693.

Modern societies aren’t immune

While few people today believe in witches that doesn’t mean that modern societies have given up the idea that there are people who are inherently disruptive or even dangerous to society. We might not always use the word “witch,” but the idea of purifying society of uncontrollable evil is still with us.

In the Jim Crow South blacks were seen as inherently disruptive to white society and formally segregated. In some cases, they were lynched.

The Holocaust followed the pattern of a modern witch hunt. The Nazis saw Jews as inherently dangerous and disruptive to social order. At first they humiliated and ridiculed them, then they segregated them in ghettos and finally they executed them.

One could argue that Americans are already accusing immigrants and Muslims of being the witches of our time. Both groups are seen by some in power as disruptive to social order by their very presence. Some even see them as inherently dangerous. Indeed, there are ongoing efforts to separate them from the United States, both by deportation and blocking their entry into the country.

Still, the U.S. has a strong judicial system, so why worry that Americans might turn to accusations of witchcraft – albeit by another name – to control behavior?

The worry is that the Trump administration has shown itself to be highly effective in exploiting informal means of social control to shape public discourse, and has repeatedly berated the judicial system as ineffective or corrupt.

If the judicial system continues to block the administration’s efforts to control Muslims and immigrants, what will the administration do next?

We need to be mindful of the consequences of identifying people as inherently disruptive to social order, as unable to control an innate evilness, or as being, in anthropological terms, witches. When we start to see witches among us, the end game is death.