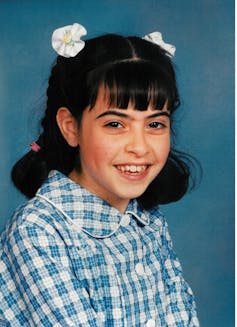

Dassi Erlich was groomed and abused from when she was in year ten, by the principal of her Ultra-Orthodox Jewish school, who knew about her difficult home life. Last year, after a 15-year campaign, her abuser, Malka Leifer, who had fled to Israel, was tried and sentenced, convicted of 18 charges of sexual abuse against Erlich and her sister, Elly. (She was acquitted of charges involving a third Erlich sister, Nicole.)

At the very end of Dassi Erlich’s account of abuse, trauma, and recovery through the slowly grinding mills of justice, she lists places where those who experience abuse may find help: including Kids Helpline, Lifeline and Women’s Legal Services.

But when her need was most acute, Erlich could not have contacted any of these services. She had absorbed the message that contact with the world outside her family’s enclosed community was a sin.

Review: In Bad Faith – Dassi Erlich with Ellen Whinnett (Hachette)

As the Royal Commission into Institutional Abuse has revealed, coercive control comes easily to patriarchal institutions – and Melbourne’s Adass Israel community is particularly patriarchal and controlling.

Adass Israel ‘evokes 19th-century Europe’

As with most ultra-Orthodox Judaism, Adass Israel originated in 19th-century Europe as a conservative reaction to liberal secularism. The cut of the men’s black silk coats worn with white shirts, and their mink hats, come from that time and place.

The Australian congregation was only formed in 1939, but the tiny enclave within East St Kilda and Ripponlea where Melbourne’s Adass Israel community lives effectively evokes 19th-century Europe.

Its members live without television, radio or secular newspapers. Internet access and telecommunications are strictly regulated. Lives revolve around the synagogue and festivals of faith. Most of the approximately 250 families are descended from immigrants who arrived as Holocaust survivors in the years after World War II. That collective memory colours responses to any perceived threat.

In this community, Erlich’s family were outsiders. Her parents had joined a generation later, as converts to Orthodoxy after emigrating from England. She notes that as a result, “my mother was on a mission to prove her worth to the Adass community”.

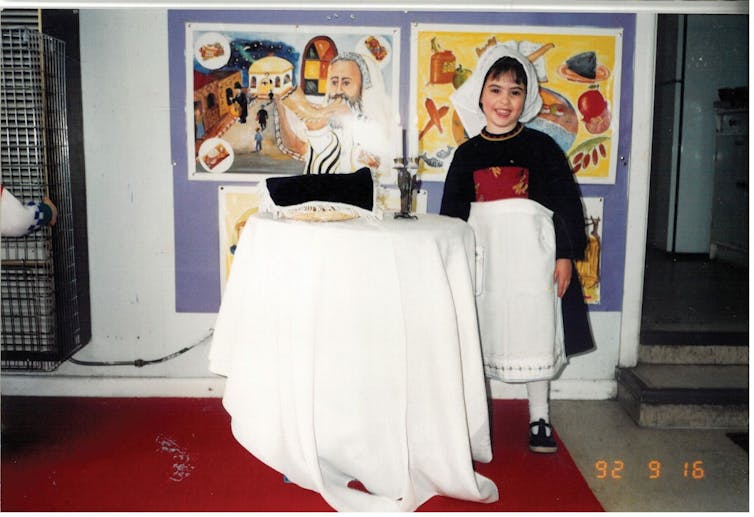

The children suffered for her ambition, and from her unpredictable rages and punishments. Erlich writes that from a young age, she realised her mother’s rage “had no rhyme or reason, no trigger we could predict”. On one memorable occasion, her mother cut the faces from her daughters’ dolls, as they were “idols”. The children were punished by being deprived of food and even the ability to go to the toilet at night.

The community’s rules are many. Women’s dresses have long sleeves, while thick stockings cover their legs. Wigs or scarves conceal their hair. Modesty is all. The 613 commandments extracted from the Torah govern every aspect of daily life, including the timing of sexual relations between married couples. There is no birth control. Large families are the norm.

People marry young, shortly after the legal age of consent. Marriages are arranged via matchmakers, and couples have few meetings before their wedding. Erlich writes that the first time she had an unsupervised conversation with her former husband, Shua Erlich, was on their wedding day.

Such is the fear of contamination by gender, unrelated girls and boys do not mix after they turn three. At the school for girls, the modified curriculum teaches to keep the commandments, to be good wives and mothers, to obey both future husbands and the religious authorities. Descriptions of animal or human reproductive organs are off the agenda.

In adolescence, Dassi Erlich became upset at the way her father would grab her and hold her close to his body, but did not understand either his motivation or her response.

Such children are vulnerable, easy pickings for predators. The Erlich sisters, with their difficult mother, were especially so.

Read more: Malka Leifer found guilty of sexual abuse of former students

‘It was just a woman’

When Dassi Erlich was in year nine, in December 2002, a new principal was appointed to the girls’ school. Malka Leifer had come from Israel with excellent references and appeared to be everything this devout congregation could desire. Erlich writes of “the respect and awe” the schoolgirls felt in the presence of this charismatic woman, who exuded authority.

At first, the child was thrilled to be noticed, to be singled out for particular attention, to be told she was “special” and not stupid. Her mother was flattered when Leifer offered to give her daughter private lessons out of school hours, to advance her religious education.

Erlich wrote of these “lessons” that “I never found my words” to object to the continuing assaults on her body. She lacked the language, the knowledge or the power to speak out. The account of her inability to escape is hard to read, but is also hard to stop reading. The abuse only ended with her wedding, in September 2006, when she was 19. Its consequences never ended.

It was only some years later, when she was in Israel and being counselled for her ongoing depression, that Erlich recognised what had happened to her. She then discovered two of her sisters had also been abused, under similar circumstances. Without language, without knowledge, they had not been able to confide in each other.

The Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse uncovered that when abuse is discovered, the standard response of many religious institutions is to conceal the evidence. It is hardly surprising the Adass community reacted to the news of the principal’s criminal behaviour in the same way.

In 2008, Leifer vanished overnight from both the school and Australia – before any formal complaint could be made. When the issue was raised, the rabbi’s response was: “Mrs Leifer should not be considered guilty of any crime as there has been no investigation.”

Given the circumstances, it is hardly surprising Erlich suffered from recurring mental health issues in the following years. Her religion controlled every aspect of her life, but could not save her from being raped. One rabbi, on hearing of Leifer’s acts of abuse, said, “What’s the big deal? It was just a woman.”

Read more: Holy Woman's fleshy, feminist spiritual pilgrimage is a warning against religious coercive control

Unrestrained power, control and authority

In the way it charts her pathway towards healing, In Bad Faith becomes more than an indictment of a fundamentalist misogynist sect. There are heroes as well as villains.

When Erlich becomes suicidal after the birth of her daughter, her husband’s liberal Jewish father pays for her admission to the Albert Road psychiatric clinic. She gives full credit to both her therapists and her fellow patients as she maps her slow walk to self-realisation and the need to reject the rules she had always lived by.

The end of her marriage was inevitable, as were her many missteps on the way to freedom. But her stumbles are relatively minor compared to the trauma she experienced.

In enclosed sects, whatever their complexion, those who leave and speak out against misbehaviour are shunned, often losing all contact with their families. In this, Dassi Erlich is fortunate: her siblings have always stood with her.

Their support was essential when she eventually made a formal complaint to the Victorian police and initiated a civil case against the school. By quoting extensively from the court’s judgement, Erlich makes clear that the formal, legal acknowledgement of the crime committed against her was just as important to her healing as the record damages she was awarded.

The response of the Orthodox Jewish community to the truths exposed by Erlich and her siblings was as expected. As well as abusive phone calls and online trolling, there has been a subtle public relations campaign.

In 2016, a year after the judge in Erlich’s civil case ruled that “Leifer’s appalling misconduct […] was built on this position of unrestrained power, control and authority that had been bestowed on her by the Board”, Adass Israel was the subject of a television documentary, Strictly Jewish.

This sanitised account of the community blithely dismisses the abuse as an unfortunate event, quickly excised. At the time the documentary was aired, members of the Adass community were continuing to actively financially support Leifer, who was living free in Israel.

Global quest for justice

In 2014, when Malka Leifer was first arrested, Australian authorities had a reasonable expectation she would soon be extradited to face trial. Instead, she was released from custody, feigning a mental illness that had turned her into a zombie-like state. There is a certain irony in a perpetrator masquerading as being mentally ill, after inflicting enduring pain on the minds of her victims.

The book details the behaviour of Israeli medical, legal and political figures in their efforts to prevent Leifer from facing trial. Medical reports were falsified, the Israeli minister for health was implicated in corruption of due process. Leifer was one of their own.

It is hard not to contrast the crude tribalism of the Israeli political establishment with that of the Australian one. Jewish politicians, both Liberal and Labor, led their colleagues in supporting the sisters’ quest to bring Malka Leifer to judgement.

Malcolm Turnbull formally raised the scandal of Leifer’s protected status in a meeting with Benjamin Netanyahu. When the extradition case stalled, the Australian parliament, in a motion jointly moved by Josh Burns, Dave Sharma and Anthony Albanese, unanimously called for Mrs Leifer to be returned to face trial. Our diplomats made it clear her presence was required.

Erlich’s account of how her predator was eventually brought to justice shows how well these siblings learnt to work with the once unfamiliar outlet of social media. After their Facebook group was trolled by Leifer’s supporters, they established a Twitter thread, #bringleiferback.

This became a conduit for supporters in Israel to reveal more information, including evidence Malka Leifer had been appointed to the school in Australia after similar acts of abuse in Israel.

Supporters infiltrated the enclosed Israeli community where Leifer was living, using concealed cameras to show the falsity of the claims made about her ill health. After the footage was sent to Interpol, she was re-arrested.

Although the extradition, trial and conviction of Malka Leifer was a group effort, full credit for bringing her to justice must go to the sisters – Dassi Erlich, Elly Sapper and Nicole Meyer. In their single-minded pursuit of their abuser, they are like the Furies, Ancient Greece and Rome’s goddesses of vengeance, hunting down those who have committed evil.

Read more: Explainer: what is extradition between countries and how does it work?

This is a very self-aware memoir: Erlich and her sisters know they need to take control of their own narrative. They’ve worked with local and international media to ensure their story – of abuse and the protection of the guilty – is fully exposed.

In Bad Faith is itself a part of this process of shaping the narrative – not the least because a draft of the manuscript became a document in the criminal trial. Dassi Erlich gives due credit to both her editor Ellen Whinnett, who is rightly credited as a co-author, and to the many others who helped her find her words. But this is her book, and one to be proud of.