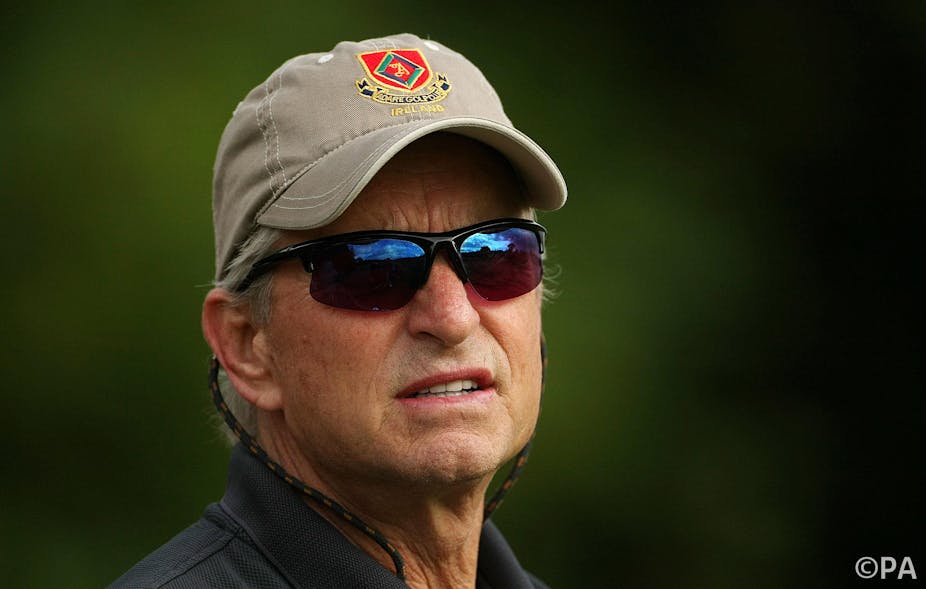

Actor Michael Douglas’ claim that his throat cancer was caused by human papillomavirus - or HPV - has generated lots of publicity. But head and neck cancers are still thankfully still very rare.

They are more likely to affect people over 50 and it’s more common in men than in women. HPV more commonly causes cervical cancer in women.

Thankfully, there is a vaccine available for the cancer-causing virus. Currently, only teenage girls are being vaccinated in the UK around the age of 12 or 13, a few years before they become sexually active. The reason all countries offered the vaccine to girls in the first instance is that it makes most sense to vaccinate those at highest risk. Nearly 3,400 women are diagnosed with cervical cancer in the UK each year so cervical this is therefore the first priority.

But despite vaccination, cases of head and neck cancer are increasing. The UK saw a 51% increase in oral and oropharyngeal cancers in men from seven per 100,000 to 11 per 100,000 between 1989 and 2006. Of course, not all of these are caused by HPV, but it is thought that around 50-60% of these cancers are HPV–related. The others are generally related to alcohol and tobacco use. Where HPV is the cause, the likelihood is that it was transmitted through oral sex.

Early research into the vaccines has also concentrated on girls, so how well the vaccines work in boys has only been established in the last couple of years.

But all this emphasis on women overlooks the fact that men are also at risk of HPV related cancers, including penile, anal and throat cancers.

Heterosexual men may benefit to a limited extent from “herd immunity” through the vaccination of girls. But concentrating only on girls has led to a number of problems.

The message is sent out that a sexually transmitted infection is “a woman’s problem”. This has led some cultural and religious groups to decide that women don’t need the vaccine as they should be monogamous – entirely ignoring the sexual behaviour of men. This leaves a gap in the vaccine regime.

There is also the issue of men who have sex with men (MSM), who don’t benefit at all from the vaccination of women. Approximately 35 in every 100,000 MSM develop anal cancer, compared with less than one in every 100,000 heterosexual men.

It has been suggested that this is a social injustice since these men, who are at risk of cancers preventable by HPV vaccination, aren’t offered the opportunity to protect themselves.

The only way MSM can be protected is by the vaccination of boys. It has also been suggested that only this group of boys should be targeted, rather than all boys. But it’s very difficult to imagine how this could work in practice, when adolescent boys are likely to be reluctant to be singled out for vaccination at school (or elsewhere) if that exposes them as being homosexual.

In 2011, the US Centers for Disease Control recommended vaccination of boys, and last year, Australia became the first country to offer vaccination to boys in a national vaccination programme.

The momentum for vaccination of boys is therefore growing, and the increased awareness of the role of HPV in oropharyngeal cancer may finally provide the push that will persuade policy makers.