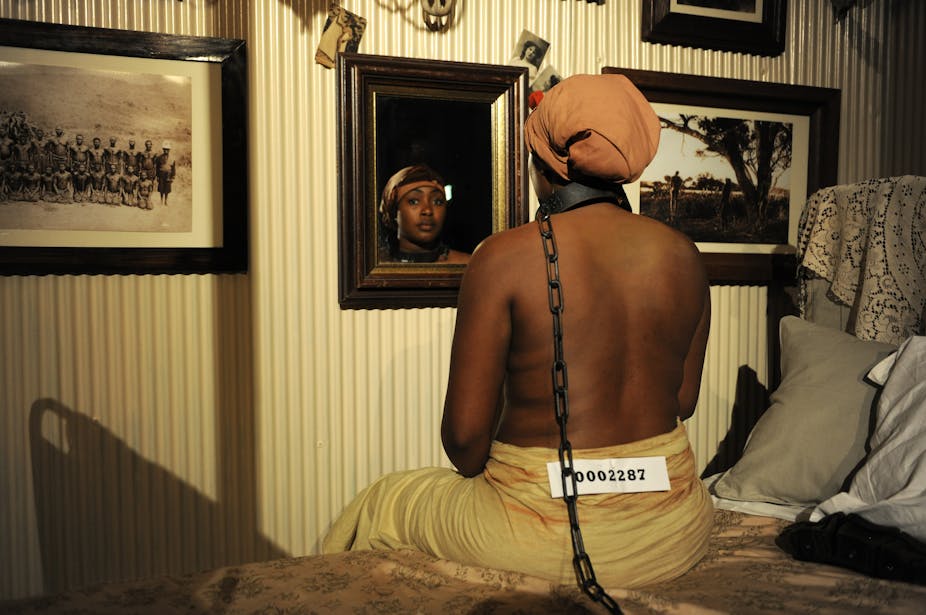

This year the Edinburgh International Festival is featuring Brett Bailey’s performance piece Exhibit B. Exhibit B presents thirteen living pictures, created with local African residents and asylum seekers. These “tableaux vivants” explore the dark history of importing and displaying foreign people. The work has drawn criticism for recreating forms of dispossession, and praise for movingly addressing the legacies of colonialism.

As early as 1493, Christopher Columbus returned from the Americas with an Arawak man, who was displayed in the Spanish court. Other Native Americans were displayed throughout the 1500s. It has even been suggested that the character of Caliban from Shakespeare’s play The Tempest was based on a Native American exhibited in London.

Early shows were rare, but by the 19th century foreign people were routinely paraded in front of millions of visitors in cities across the globe, including London, Paris, Berlin, and New York. Up until the mid-1800s, exhibitions typically lasted a summer season, and were usually privately financed.

At first, entrepreneurs and missionaries haphazardly imported individuals or small groups to be displayed in galleries, theatres, museums, and private rooms. For a shilling or more, the public could see groups of Sámi, South Americans, Inuit, Native Americans, Africans, Arabs, Pacific Islanders, Australian Aborigines, Indians, Japanese, Chinese, and “Aztecs”. These men, women, and children were often colonised peoples who performed songs, dances, and ceremonies for eager patrons.

Sara Baartman, the ‘Hottentot Venus’

One of the most famous figures represented in Exhibit B is Sara Baartman. She stands isolated and half-naked on a pedestal, waiting to be examined. The original Baartman was exhibited in Piccadilly as the “Hottentot Venus” just three years after the abolition of the British slave trade in 1807. Antislavery campaigner Zachary Macaulay accused Baartman’s manager, Hendrick Cesars, of keeping her as a slave.

Ultimately, Cesars produced a contract signed by Baartman, in which she consented to be exhibited. We still don’t know how well she understood the terms of this contract, or if she was coerced into signing, but it was enough for Cesars to win the case and set a legal precedent that is still cited today.

Baartman died in Paris in 1815, and was quickly dissected by the most famous anatomist of the day, Georges Cuvier. He preserved a plaster cast of her corpse, skeleton and genitals. Her remains were displayed in Parisian museums until the 1980s. They were only returned to South Africa in 2002, after an eight year campaign endorsed by presidents Nelson Mandela and Thabo Mbeki.

Visual encyclopedias

Foreigners were imported in much larger numbers following London’s Great Exhibition of 1851. That celebration of international trade started a whole genre of display throughout Europe, America, India, Africa, and Australia. The fairs were designed to be visual encyclopedias, to entertain and educate visitors over a few short months.

At first, foreign people appeared as servants or shopkeepers. By the end of the century, they usually worked as “professional savages” in mock “native villages” that were designed to showcase architectural styles ranging from Zulu Kraals to Philippine water bungalows. The remainder usually worked as colonial labourers, producing market goods.

In the 1886 London and Colonial Exhibition featured dozens of “living natives”. These foreign peoples worked in cafes, in a model diamond mine, or in demonstrations of Indian crafts.

The fairs were such an attraction that attendance figures ran into the tens of millions. After World War One, their popularity waned. The practice came under fire from anti-colonial campaigners, particularly from nations in Africa and India.

What’s the attraction?

Displayed people drew enormous crowds for three main reasons. Even in ethnically diverse cities such as London, it was hard to do anything more than look at foreigners. Paying a shilling or more allowed visitors to ask questions and interact in ways that simply weren’t possible on the streets. Some encounters led to intimate connections.

In 1899, news broke that Kitty Jewell had become engaged to the star of the Savage South Africa exhibition at Earl’s court, Prince Peter Kushana Lobengula. The interracial engagement attracted intense criticism, but the couple were eventually married and Lobengula is now buried in Salford. Such stories are important reminders that the shows became opportunities for many people to build careers, meet spouses, and settle abroad.

The shows were also flash points for political discussion. Managers attracted custom by emphasising the political relevance of their shows. For example, during the 1879 Anglo-Zulu War, the Great Farini imported a troupe of “Friendly Zulus,” much to the dismay of many MPs.

Throughout the 19th century, people also debated whether performers were slaves or not, and whether their contracts were valid. These discussions played an important role in defining the nature of consent.

These exhibits were also of immense interest to scientists, especially anthropologists. Performers were physically examined, photographed, described in scientific papers, dissected, and made into plaster casts. In this way, scientific collections of body parts and artifacts across the world were built up to define what race meant and how it should be used to create racist hierarchies.

The history of displayed people is painful, and this explains why Exhibit B has been so controversial. This show has the power to remind us how racism has led countless individuals to be dehumanized and denied fair treatment because of their ethnicity. By interspersing the stories of past performers with present day asylum seekers, Bailey forces us to consider if we are still entangled by the legacies of European colonialism, and challenges us to confront modern racism.