One of my highlights of my time in coalition was … that the attainment gap, namely how well poor kids do in school as opposed to their wealthier classmates, was closing for the first time in a very long period of time and the reason why that appears to be the case, was because of the effect of policies like the pupil premium.

Nick Clegg, Liberal Democrat leader, on the Radio 4 Today programme.

With the Liberal Democrat leader set on highlighting the impact his party has had on the coalition’s education policies, Clegg said he is heartened that there are signs the attainment gap is narrowing. In particular, he has pointed to the impact of the pupil premium, which was introduced in April 2011, and provides additional funding to schools for each pupil who is eligible for free school meals. The pupil premium is now £1,300 per year for pupils in primary school and £935 per pupil in secondary school.

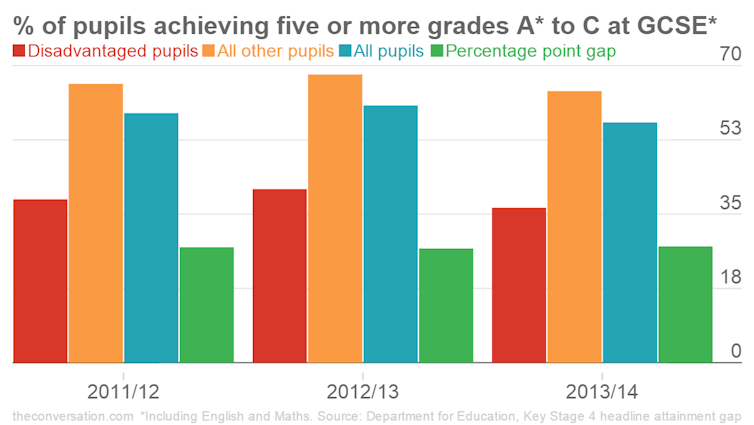

Clegg’s response that the attainment gap between the poor and their wealthier classmates was narrowing, came in response to questions about a recent analysis by the think tank DEMOS, which seems to contradict this. The DEMOS analysis was based on GCSE results from 2014 and indicates that the attainment gap widened in 72 out of 152 local authority areas last year.

In 66 areas, the gap was larger than it was two years previously, before the pupil premium was introduced. Across England, DEMOS said that the attainment gap for free school meals pupils was 26.7% in 2013-14, up from 26.4% in 2011-12 but reduced from 27.5% in 2010-11 when the pupil premium policy was introduced.

The Department for Education revised figures, released in March 2015, are slightly different, though actually worse for 2013-14. The graph below shows the percentage point gap was at 27.4% for 2013-14, up from 26.9% in 2012-13.

Part of what explains this difference is the change in assessment in 2014. Some qualifications no longer counted as an equivalent to a GCSE, and only pupils’ first entries in “English Baccalaureate” subjects were included, so this impacts on how results are counted in performance measures. These reforms have had a significant effect on the 2014 GCSE and equivalent results and school league tables. Care should therefore be taken when comparing 2014 results with earlier years as they are not exactly equivalent.

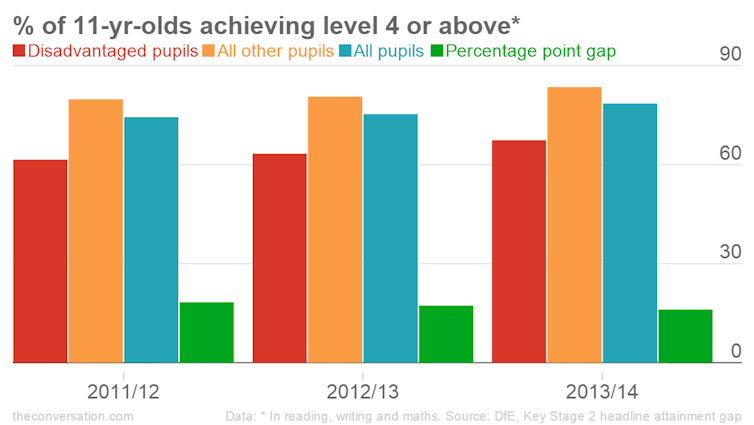

By contrast, the data for 11-year-olds shows a different picture. The proportion of children achieving the expected level in reading, writing and mathematics at the end of primary school has increased since 2011-2012.

Last summer, 67.4% of disadvantaged pupils achieved this level, with 83.5% of other pupils reaching this “expected” level in 2014. Test results for this target have been rising for disadvantaged pupils so the attainment gap has narrowed.

The gap in attainment between poorer pupils and their wealthier peers reduced by 1.3 percentage points last year from 17.3 to 16.1 percentage points, and since 2012, this gap has narrowed by 2.2 percentage points.

Verdict

Overall Nick Clegg’s claim is a reasonable one: there has been some progress in “narrowing the gap”, particularly for children at primary school. But the DEMOS report also makes the point that a family’s level of income continues to remain a key predictor of their child’s educational success. This is still a significant challenge.

It is difficult to know to what extent the pupil premium is the cause of any change, as another significant policy shift is the monitoring of the attainment gap at all. This has certainly focused attention in schools on any difference in attainment of pupils receiving free school meals compared with other pupils.

It is difficult to be certain that it is the pupil premium which is responsible for the change, though perhaps fair to argue that it has played its part.

Review

The fact check provides a fair and nuanced picture of achievement levels in English primary and secondary schools, and specifically the gap in achievement between richer and poorer students.

The author is correct that in recent years, there has been no narrowing of the GCSE achievement gap between children who are eligible for free school meals and those who are not. There has indeed been a small reduction in the socioeconomic gap in achievement at age 11, Key Stage 2.

There are a number of possible explanations for these trends and the fact check is correct when it states that the improvement in the socioeconomic gap in achievement at age 11 cannot be specifically attributed to the pupil premium. Nor, of course, can we discount the possibility that the socioeconomic gap at GCSE would have been bigger without the pupil premium. There is just insufficient evidence to establish the causal impact of the pupil premium.

An important point is also raised about the impact of the recession on the proportion of children receiving free school meals. It is not simply a question of numbers. If the achievement of children who are temporarily eligible for free school meals due to the recession is higher than children whose families are on benefits for a longer period of time, then the gap between free school meal and non-free school meal children will narrow. This is not because of success in the school system but because of changes in the composition of the two groups.

Click here to request a check. Please include the statement you would like us to check, the date it was made, and a link if possible. You can also email factcheck@theconversation.com