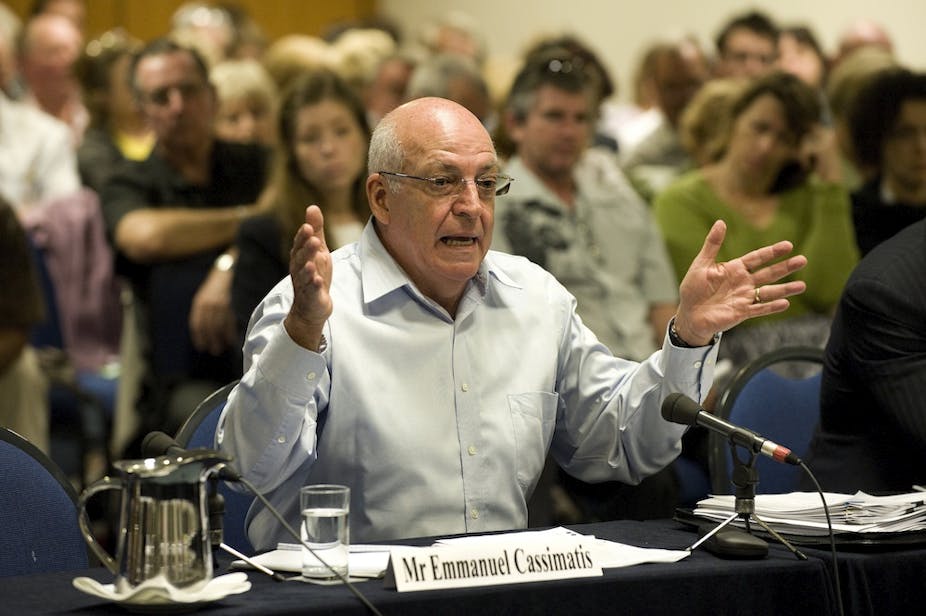

When financial planning firm Storm Financial collapsed with $3 billion in investment losses, many of its investors were left destitute. A parliamentary joint committee inquiry into the company’s demise was conducted in response and, in 2010, then Financial Services Minister Chris Bowen announced a series of sweeping reforms aimed at giving greater protection to retail investors.

The Future of Financial Advice (FOFA) reforms are due to come into force on July 1, 2012. The proposals are intended to minimise conflicts of interest and restore confidence in the financial advisory sector. The proposals include: a ban on commissions and rebates on a prospective basis; a requirement for clients to opt in for advice every two years; a duty for financial advisers to act in their client’s best interests; a ban on percentage-based fees on geared products and portfolios; allowing superannuation funds to provide simple intra-fund advice at minimal or no cost to members; and further powers for the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) to act against unscrupulous advisers.

The fundamental purpose of the proposals is to prevent consumers from suffering investment loss arising from inappropriate advice. The most devastating example is attributed to Storm, where about 4000 clients suffered losses estimated to be $3 billion. The advice was based around “double gearing” - by borrowing against the client’s house and then using margin lending to invest heavily in the sharemarket. The undoing of this strategy was the global financial crisis when share values fell heavily and the lenders called in loans – both against the shares and against the client’s house. Yet Storm had complied with procedural requirements of the law at the time. The model used by Storm could exist in the future for some clients, except for a modification to the remuneration method.

Where Storm’s advice model came unstuck was when they applied a similar strategy to a large number of clients, where it was argued that the advice was not appropriate in many sets of circumstances. The proposed “best interests” provision is a change from the current law as the adviser will be required to put the client’s interests first and above the adviser’s own interests. This is a laudable and ethical move, but can this be enforced? Under the best interest duty, an adviser is required to only give advice that is appropriate for the client. This will replace the current rule, which states that an adviser must provide a “reasonable basis for the advice”. In describing the best interest provision, the term “reasonable” is used a number of times, which indicates that subjectivity of what is reasonable will be the order of the day.

The current rules would have ruled out the Storm advice for a number of clients as the advice would have been deemed not to have been reasonable given the circumstances of each client. This matter is currently before the court under existing legislation. However, it may have been appropriate for some clients and under the new rules the same strategy could be appropriate for some particular clients as well. The Storm disaster is seen as the reason behind the changes to the laws governing investment advice.

Under the proposals, a financial adviser that charges fees for ongoing advice will be required to send a notice to the client requesting the client to agree to renewal of the service contract, otherwise the adviser must cease invoicing the client. Such a proposal adds costs to the operations of a financial planning practice, yet is designed to ensure that clients do not pay for any services that they do not receive. It is a worthy addition to the objective of consumer protection.

However, the FOFA reforms reinforce an inconsistency in the intent of the proposals. The proposal to allow intra-fund advice by institutions and superannuation funds reflects a conflict of interest, as the advice can hardly be seen as independent. When a member of a fund seeks advice from the fund in which they are a member, it is extremely unlikely that the member will be advised to invest elsewhere, other than in the same fund. With intra-fund advice encouraged by the proposals, this is likely to result in limited advice provided to consumers, which is not focused on the whole of the client’s needs but solely on their superannuation fund interest pertinent to that particular superannuation fund. This proposal is likely to push consumers more towards limited and conflict-ridden advice than that which existed before.

Furthermore, the advice offered by intra-fund means is generally paid for by the fund out of charges levied for the administration of the fund. Yet the banning of an alternate form of remuneration for advice in the form of commission is also seen as inconsistent. The allocation of payment for advice offered by superannuation funds is not declaredm yet the commission paid by retail investors is declared to the consumer. So, on the one hand, the proposals are aimed at seeking independence and objectivity; on the other, the institutions – banks and industry superannuation funds - control much of the product manufacture, distribution and the associated advice offered to consumers.

The enhancement of ASIC’s powers will capture all financial advisers (including those who are salaried employees), whereas at present, only those who are known as “authorised representatives” are known to ASIC. This will enable ASIC to ban employed advisers who can move from employer to employer under the current arrangements.

It might be said that the government has missed an opportunity to break the nexus between the manufacturers, distributors and advisers, but instead has provided a means of reinforcing the integration of product and advice and conflict of interest. It may be argued that this reinforcement of a conflict of interest scenario is a trade-off with the breaking of the up-front and trail commission element of the current situation, eliminating many independent advisers under the argument that a reduction of costs to retail consumers will benefit their superannuation balances in the long run. Overall, it is seen as a win for the institutions and the industry superannuation funds.