How will Donald Trump observe Presidents Day?

Will he have the inclination or take the time to read about or reflect on the qualities of our greatest leaders?

Given how busy Trump is issuing executive orders, fighting with the judiciary, managing the scandal surrounding the dismissal of his national security advisor, becoming acquainted with world leaders and tweeting, the answer is probably no.

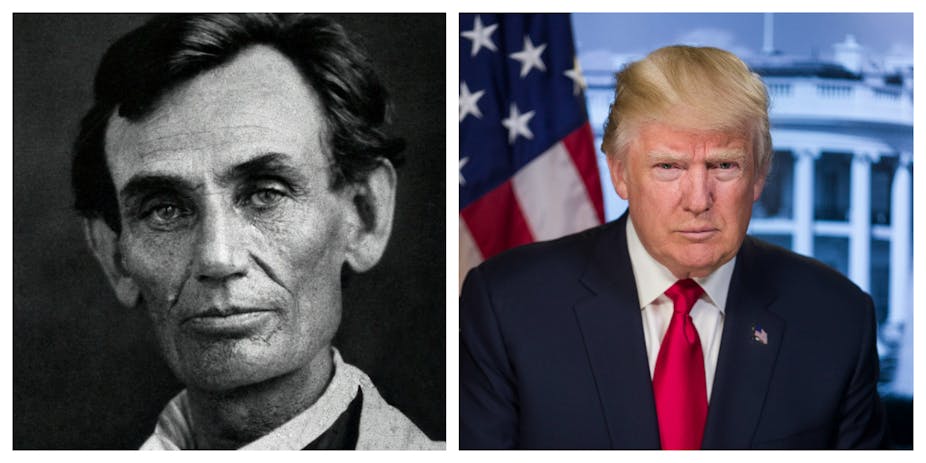

As a historian who has studied presidential leadership for decades, perhaps I can save him some time by suggesting a few things he might learn from the first Republican president, Abraham Lincoln.

Lesson 1: Grow a thick skin

Lincoln was more reviled than any American president. The opposition press described him as a “fungus from the corrupt womb of bigotry and fanaticism,” a “worse tyrant and more inhuman butcher than has existed from the days of Nero” and “a vulgar village politician without any experience worth mentioning.” Even Lincoln’s now-classic Gettysburg Address was derided as a display of “ignorant rudeness.”

These attacks stung, but Lincoln refused to take the bait. “No man resolved to make the most of himself, can spare time for personal contention,” he wrote. “Still less can he afford to take all the consequences, including … the loss of self-control.” Lincoln realized that getting into the gutter would diminish his stature, distract the public from important issues and burn crucial political bridges. “A man has no time to spend half his life in quarrels,” he advised a political ally. “If any man ceases to attack me I never remember the past against him.”

If Trump doesn’t dial back his attacks – which so far have included invectives against Meryl Streep, Alec Baldwin, Madonna, John Lewis, Charles Schumer, John McCain, Lindsey Graham, a growing list of federal judges and the CIA – he will appear more petulant than presidential.

Lesson 2: Engage your critics strategically

Lincoln occasionally responded to critics – but always civilly, always strategically.

When, in 1862, Republican editor Horace Greeley charged that Lincoln’s unwillingness to end slavery sabotaged the Union war effort, Lincoln replied in a public letter. He had already decided to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, but gave the impression that he was agnostic on the matter. With respect to slavery, Lincoln told Greeley, his policies would be dictated by what best served the Union cause. By tying his position to preserving the Union, Lincoln laid groundwork for making his ultimate decision more palatable to the many Unionists – in the North and the border states – who supported slavery. He did so without insulting Greeley and other abolitionists and concluded his letter by emphasizing common ground: “I have here stated my purpose according to my view of official duty; and I intend no modification of my oft-expressed personal wish that all men every where could be free.”

Trump has yet to absorb the lesson that in the world of presidential communications, less is more – especially when the less is carefully crafted, strategic and cultivates those whose support is needed. For Trump, that means the majority of Americans who didn’t vote for him and who have given him the lowest approval ratings of any incoming president in modern times.

Lesson 3: Be informed and ask questions

Aside from a brief stint as a militia volunteer in the 1830s, Lincoln had no military experience. Nevertheless, he was a war president and helped to develop the grand strategy that crushed the Confederacy.

How did he do it? By reading extensively on military strategy and tactics and meeting frequently with his secretary of war and generals, asking them questions and discussing military operations. He spent countless hours in the War Department telegraph room, reading and sometimes responding to telegrams from the front, and often visiting armies in the field. While he gave the generals wide latitude, he remained curious, focused, well-informed and critical to the Union’s military success.

To develop effective policies on the issues he cares about, Trump must become better-informed. He should demand briefings on key issues from a variety of experts (especially those who oppose him), read them thoroughly and ask questions. Rather than glibly promise that Republicans will quickly repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act with a plan that expands coverage, lowers costs and increases choice, he should learn about the complexities of health care and the inevitable trade-offs involved in replacing the ACA. Raising hopes only to dash them in fairly short order is neither good leadership nor good politics.

Lesson 4: Adapt, change and grow

Consider Lincoln’s position on slavery, race and citizenship. Lincoln opposed slavery, but he established restoration of the Union – not emancipation – as the Union’s war aim.

When he became president, Lincoln knew few African-Americans, probably saw them as inferior to whites and occasionally told racist jokes. As president, he listened to and learned from abolitionists who were among his most outspoken critics. They included radical Republican Sen. Charles Sumner and African-American abolitionist Frederick Douglass, whom Lincoln collared after his Second Inaugural Address to ask his opinion of the speech. Critics of slavery helped Lincoln understand how emancipation and enlistment of black troops would undermine the rebellion, leading him to embrace emancipation and reframe the Union’s war aims to include liberty as well as Union. Abolitionists also helped him understand that African-American citizenship was essential to make the war’s promise of “a new birth of freedom” a reality. In a speech delivered three days before his death, Lincoln embraced the radical position that blacks who had served in the military or were literate should have the right to vote.

Trump comes to office with an understanding of issues that reflects his campaign rhetoric. He cannot hope to leave this country better than he found it unless he listens to critics as well as supporters on a wide range of issues. Let’s start with terrorism. He may have proposed a Muslim ban during the campaign, but now’s the time to develop a nuanced view of Islam at home and abroad and listen to national security experts who understand the perils of targeting Muslims.

Lesson 5: Use words carefully

Lincoln had less than a year of formal education, yet he was among our most literate presidents. A voracious and eclectic reader, he appreciated the beauty and power of language and used his understanding to become a formidable writer. In the age of the telegraph, presidents communicated with the nation through the written word – speeches, open letters and state papers published in the press.

Lincoln worked hard to become a writer. As president, his precision and eloquence enabled him to make the case for the Union and the unimaginable sacrifices its preservation required. Lincoln defined the war as a “people’s contest,” a struggle to vindicate the efficacy of America’s founding principle – the right of people to govern themselves. His formulation of the principle evolved from the 1830s through his presidential addresses and achieved its most powerful expression in the Gettysburg Address. Skillfully weaving together emancipation and self government, he explained to a war-weary public that their sacrifices would forge “a new birth of freedom” that assured that America’s founding principle – “government of the people, by the people, for the people” – would “not perish from the Earth.”

While Trump enjoyed vastly more formal education than Lincoln, he is neither a reader nor a writer. He connects with supporters who find his barroom-like riffs “authentic” and honest. But as a candidate who lost the popular vote decisively, he must reach beyond his base to succeed. To do so, he must use language more precisely and persuasively. Should he continue to issue poorly crafted policy statements – such as his executive orders banning entry to the U.S. by residents of seven predominantly Muslim nations – he will spend his time walking back his positions, defending ill-conceived actions in court and undermining confidence in his competence. If he continues to appeal to fear and narrow self-interest rather than forge a vision rooted in shared values and aspirations – as did Lincoln, FDR and Reagan – his presidency will fail and the country will suffer. Here again he should listen to Lincoln, who appealed to “the better angels of our nature” in the face of secession and imminent war.

If Trump wants a reset that will help him – and the country – succeed, there is no better guide than POTUS 16.