When I was at primary school in the late 1970s, engaging kids in history lessons meant a good dose of role-play. Each year, on today’s date, it was time to re-enact the Eureka Stockade.

It was on this day in 1854 that Ballarat’s aggrieved mining community – protesting a host of local and constitutional injustices, including what they saw as an unfair tax system – was attacked before dawn by government forces while sheltering behind a rough palisade. At least 30 miners and four soldiers died in what is commemorated every year on December 3 as Australia’s only act of armed civil disobedience by white Australians.

The event has since become a key foundation stone in the story of Australian nation-building.

At my school, we remembered the occasion like this: half of the class got to be the miners. The other half was the soldiers. One very blessed boy was picked to be Peter Lalor, the activist-turned-politician who led the Eureka rebellion.

We pointed our imaginary guns at each other across the room — a barricade of extruded plastic chairs between us — and shot to the death. More miners got to fall to the floor in wounded agony than soldiers. Lucky Peter Lalor had his arm blown off. The lesson was that the gold diggers lost the battle but won the war. They fought for our rights and freedoms.

It was boring and dumb and nobody much cared; least of all the girls who found limited joy in the bang-bang-you’re-dead gun play.

By high school, we’d dropped the charades but the compulsory curriculum unit on Eureka and the gold rush was hardly more thrilling. Now phrases such as “birth of democracy”, “manhood suffrage” and “no taxation without representation” came attached to the morality tale. The brave men of Eureka took a stand against tyranny and died in defence of liberty. Is it lunchtime yet?

Statistics show that the optional study of Australian history is in decline. Is that because there are too few role models in the standard telling of history for us to identify with?

In the storyboarding of Australian history, too often there have been lead parts for men, but no leading ladies.

But far from being source of the problem, could the Eureka Stockade in fact be key to the solution?

Beyond the boys-own mythology

Recent research has revealed that the Eureka legend has short-changed the true richness and complexity of the event itself. Stripped of its (white, Anglo) boys-own mythology, Eureka stands as a rip-roaring tale of drama, intrigue and extraordinary characters.

In the book Black Gold, for instance, Ballarat historian Fred Cahir has documented the ingenuity and economic opportunism of the Wauthurung people when faced with the tidal wave of goldseekers to their country around Ballarat in the early 1850s.

My book The Forgotten Rebels of Eureka reveals, in all their vitality and diversity, the remarkably unbiddable women of Ballarat.

The truth is that when the British soldiers stormed the flimsy citadel on Sunday December 3 in 1854, they knowingly fired on a civilian population that included women and children.

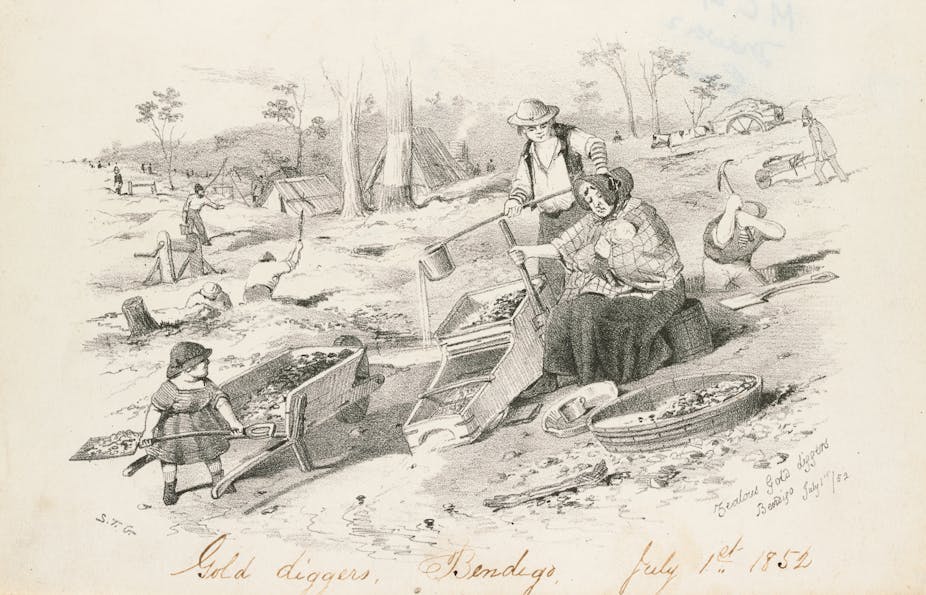

The Victorian goldfields were not simply an isolated frontier populated by rugged men hell-bent on making a quick buck. By the end of 1854, a third of the Ballarat community was women and children.

At least one woman was killed in the Stockade clash, “mercilessly butchered by a mounted trooper” as eye-witness Charles Evans recorded in his diary on December 4, 1854. How my primary school buddies would have peed their pants with excitement to play her part!

Or the part of Englishwoman Ellen Young, the self-proclaimed “Ballarat poetess”, who gave voice to the collective grievance of her community by publishing politically charged poetry and fiery letters to the editor in The Ballarat Times.

“We, the people,” she fumed, “demand cheap land, just magistrates, to be represented in the Legislative Council, in fact treated as the free subjects of a great nation”.

Or Clara Seekamp, an Irish single mother of three who became the de-facto wife of Henry Seekamp, editor of The Ballarat Times. Together, they ran the profitable printing and publishing business until Henry was jailed for sedition after the Stockade, making Clara Australia’s first female newspaper editor.

Clara continued to fire off blistering editorials, prompting one startled Melbourne journalist to fret over “the dangerous influence of a free press petticoat government”.

Or Sarah Hanmer, the Scots-Irish entrepreneur and activist who ran Ballarat’s Adelphi Theatre, which acted as the headquarters of the group driving the push for constitutional change, the Ballarat Reform League.

Then there was Catherine McLister, wife of a British policeman living at Ballarat’s Government Camp, who laid a sexual harassment case against Police Inspector Gordon Evans only weeks before the Stockade clash. (Evans, according to McLister’s sworn testimony, trapped her in his room, put his arm around her waist, dropped his drawers to “expose his person” and said, “Look at this”.)

There was also Lady Jane Hotham, the high-spirited new bride who accompanied her husband, the Governor of Victoria, to the colonies and left again less than a year later as a widow.

I’d put my hand up to play publican Catherine Bentley, tried for the murder of miner James Scobie who was killed outside the Eureka Hotel.

Catherine lost everything when rioting miners (including women) burned her hotel to the ground. Pregnant at the time, and with a toddler, she was forced to jump from the second floor of the flaming pub into the arms of the same crowd that was baying for the Bentleys’ blood. She later hounded the government for compensation for the destruction of her home and business to the tune of 30,000 pounds.

A story for all Australians

The fact that none of these women’s names is as familiar to us as that of Peter Lalor points to the inherent gender bias of Australian nationalism.

In fact, men and women from many lands stood together beneath a new flag. The flag bore the symbol of the constellation that located and united them in their new home — the Southern Cross. That flag was almost certainly sewn by the women of Ballarat.

Under that flag, the men of the Ballarat Reform League swore an oath to stand truly each with other and fight to defend their rights and liberties. Women were at that meeting too. At the time, they called the flag “the Australian Flag”.

This is not fiction and there is no need to invent parts or script lines. We all belong to this story. For, as The Ballarat Times’ Clara Seekamp wrote in one of her “dangerous” editorials:

What is this country else but Australia? Is it any more England than it is Ireland or Scotland, France or America, Italy or Germany? … The latest immigrant is the youngest Australian.

Happy Eureka Day.