In late 19th-century Australia, a husband could legally rape his wife. Officially, he was still allowed to do so, in some Australian jurisdictions, until as late as 1994. Legal traditions inherited from the British Empire included coverture, the notion that a wife lost her legal identity upon marriage – and thus her ability to consent to sex.

Yet over a century before it was criminalised, two key groups of women – colonial writers and suffrage agitators – began to criticise a husband’s legal right to rape his wife.

These criticisms took many different forms, ranging from self-published feminist journals to novels, short stories, serial fiction and poetry. Ada Cambridge’s poem, A Wife’s Protest, was one such example, with lines such as:

I lay me down upon my bed,

A prisoner on the rack,

And suffer dumbly, as I must,

Till the kind day comes back

This poem was published in Cambridge’s 1887 poetry collection Unspoken Thoughts. The title was a misnomer, for such thoughts weren’t unspoken. In fact, they formed part of a wider discussion about marital rape, consent, domestic violence and women’s bodily autonomy taking place in the pages of colonial women’s writings.

Feminist writers such as Cambridge, the wife of a clergyman in regional Victoria, Louisa Lawson, an inventor, poet, and newspaper proprietor, and Queensland-born Rosa Praed, linked marital rape to other forms of domestic violence, such as physical violence, economic abuse, and what we would now term coercive control.

For Cambridge and Lawson, exploiting the Gothic genre in their writings allowed them to depict marital rape, while avoiding censorship from their publishers. Horror-inducing imagery and references to torture and torture devices (such as “the rack”) enabled them to paint marital rape in a graphic light, capitalising on public appetites for Gothic stories.

In Cambridge’s novel Sisters (1904), for example, one of the four titular sisters, Mary Pennycuick, attempts to drown herself after receiving a marriage proposal, perceiving marriage itself as “a means to commit suicide without violating the law”.

She is “saved” by the village parson, who uses his chivalrous act as a bargaining tool to coerce Mary into marrying him instead. In an explicitly Gothic moment, “the white frock which she had tried to drown herself” in is “dried and ironed to make her bridal robe”.

On her wedding night, as she is led to the marital bedchamber by her husband, Mary shrinks “back from it with a shriek”, clinging to her sister-in-law:

‘Save me! Save me!’ was what the desperate clutch meant, but what the paralysed tongue could not articulate.

After the wedding, Mary is described as “a prisoner for life, bound hand and foot, more pitiable than she would have been as a dead body fished out of the dam”. With this sentence, Cambridge implies that, throughout the course of the marriage, Mary endures marital rape.

In Cambridge’s earlier serialised newspaper story Dinah (1880), the character of Dinah remarks after her husband’s death “now she will have a little peace”. The “wretchedness she had” with him had left her in bed many times, “prostrate […] with slow tears trickling down her cheeks”.

Widely-read serials, such as Dinah, made Cambridge a household name before she burst onto the international market in the 1890s.

Read more: The long history of gender violence in Australia, and why it matters today

For Lawson, who ran The Dawn, the longest running feminist journal in Australia, marital rape was a constant focus of her writing. Her outspokenness – partly facilitated by her ability to self-publish her journal – made her an outlier among her suffragist sisters.

In a July 1890 article titled The Legal Link, Lawson criticised the laws permitting husbands to commit “abominations known to women but which must not here be named”.

Her frankest description of marital rape appeared in one of her editorials earlier that year, in which she advocated for divorce law reform, drawing on the experiences of the “sad-eyed women who used to come in and tell tales of violent husbands and dreary homes”. In the article, she described how a husband could approach “his lawful wife’s chamber” and “proceed to make the night hideous for her”. Marital rape was a “horrid ordeal” that wives were “expected to endure nightly”.

Lawson represented marital rape as wives’ inescapable “fate” under marriage laws that denied them bodily autonomy. She never used the word “rape” to describe this act. But her use of Gothic tropes, describing the marital bedroom as a “chamber of horrors”, made her meaning unmistakable.

It is difficult to quantify how widespread martial rape was at this time – there is minimal historical research on the subject – but the fact that these women wrote about it widely suggests it was commonplace.

Read more: Australian Gothic: from Hanging Rock to Nick Cave and Kylie, this genre explores our dark side

Censoring criticisms

Rosa Praed, who became something of a literary celebrity when she moved to London, wrote in the romance and domestic realist genres, and was known for her depictions of the brutalities of marriage.

In her stories An Australian Heroine (1880), which some have described as semi-autobiographical, and December Roses (1892), Praed framed marital rape in moral terms. She differentiated between physical violence and “immoral” violence – the latter being coded language used to convey the idea of sexual violence while escaping her publishers’ censorship.

In An Australian Heroine, the antagonist George Brand justifies his sexual abuse of his wife Esther by telling her: “you are mine now, remember, and I may do what I like with you”.

Esther subsequently understands her marriage as “nothing but a degrading prostitution from which she could not escape”, which has “upon her the effect of a slow moral suicide”.

Unlike Cambridge or Lawson, Praed’s depictions of marital rape attracted criticism and censorship. Her 1881 novel Policy and Passion originally featured a chapter in which a fiancé attempts to rape his soon-to-be wife. Although Praed wanted to call “a spade a spade” and depict this sexual coercion and violence, her publishers declared it “too realistic” and “repugnant”. She was told to “tone down” and avoid “the suggestion of any undignified scuffle or of any actual brutality”.

Not only did her publishers object to any discussion of marital rape, they particularly objected to these discussions coming from a female author. They told her: “One has to remember that it has your name on the title page, and that you cannot so well say what [a] Mr Praed may”.

In the end, the chapter was cut entirely, and replaced with a short scene where the fiancé merely attempts to kiss his wife-to-be, which she manages to avoid.

Citizenship versus consent

Other women discussing marital rape – namely suffrage agitators such as Rose Scott and Maybanke Anderson – thought about the problem in a completely different way.

To achieve their goals of suffrage and political citizenship for women, they evoked women’s rights as mothers rather than as individuals. For these women, a wife’s ability to choose whether or not she had children and the consequences of her lack of choice for the children themselves were the problem, not the lack of consent.

Cambridge’s poem An Answer, for instance, featured a wife railing against “the yoke of servitude” and complaining about surrendering “soul and flesh that should be mine, and free” to her husband. But in Scott’s annotated copy of the book containing An Answer, she wrote in the margin: “this poem is the one [I am] sorry is in this book”.

Sydney-based Anderson, a foundational member and later president of the Womanhood Suffrage League, established her own feminist journal Woman’s Voice in opposition to The Dawn. She framed her criticism of marital rape around its effects on wives’ and children’s health, calling for women to realise “the dangers that beset them”.

Some of the discussion of marital rape in Woman’s Voice was concerned with wives’ bodily autonomy (or lack thereof). One article criticised the “laws [which] do not recognise the right of the wife to her own body”. The focus always returned to what Anderson described as “the mother’s right to choose”.

These concerns around marital rape and the “animal nature” of husbands, framed around concerns for both mother and child, were graphic. As Anderson wrote in one editorial:

It is by no means the exception, but rather the rule, that during pregnancy the wife must yield to the demand of the husband’s lust, not occasionally but constantly – as often as there are nights in the month; and not unfrequently must she give herself up to this awful harlotry before her baby is two weeks old.

In their desire to fulfil the role of wife, women’s “ruin [was] practically compulsory”.

Domestic violence

For suffrage agitators, not only was marital rape an entirely separate issue to that of domestic violence, but domestic violence was not deemed worthy of their focus. In a letter to the editor published in Woman’s Voice in 1895, Mary Sanger Evans, a prominent member of the Womanhood Suffrage League in Sydney, went so far as to declare: “The reign of brute force is rapidly on the wane”.

Both Evans and Anderson had benefited from the recently amended NSW divorce act, which enabled them to divorce their husbands on the grounds of physical violence/cruelty and economic violence/desertion respectively.

For Cambridge, Lawson and Praed, however, marital rape could not be disentangled from other forms of domestic violence. The husband who turns the marital bedroom into a “chamber of horrors” in Lawson’s editorial, also bruises his wife’s flesh “and perhaps breaks her bones”.

In Cambridge’s Dinah, the husband subjects his wife to a regime of humiliation, economic control and psychological abuse, while in another of her serialised stories, Against the Rules, marital rape is paired with physical abuse. Cambridge depicts marital rape as the worst form of a broader system of domestic violence that ensnared colonial women. “There were worse things than blows”, the wife declares in this story.

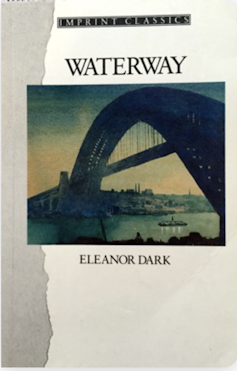

Cambridge and Praed continued to address marital rape in their fiction up until the start of the first world war, when both women began to wind up their literary careers. Throughout the mid-20th century, other female writers would tackle the topic, including Eleanor Dark, in her novel Waterway (1938), Katherine Susannah Prichard in The Roaring Nineties (1946) and Ruth Park in The Witch’s Thorn (1951).

Yet despite this continued literary attention, social, cultural and legal attitudes towards marital rape were inconsistent for many decades.

Not that Cambridge, Lawson and Praed were preaching to an empty choir. From the 1890s, in the wake of these women’s writings, some women used their divorce petitions to assert their right to consent. They described their husbands’ sexual cruelty as rape – “against their will” and “against their consent” – revealing a burgeoning feminist consciousness among wives.

In making this sexual violence public, such women laid the foundation for those who would finally be freed nearly a century later, when, in the 1970s, South Australia began to lead the charge in criminalising marital rape.