Art institutions are facing a reckoning over colonial histories and racist legacies. Though the issues aren’t new, calls to unpack the British art museum and heritage sector’s ties to colonialism have increased significantly over the past decade. As a result, institutions like the Museum Association, Pitts Rivers and Bristol Museums have begun to explore what it means to “decolonise” – the practise of exposing and undoing systems that reproduce colonial legacies – a museum.

Many of these projects include investigations into how items in museum collections were acquired and how they are interpreted and displayed. In some cases, this involves reviewing the processes of returning looted artefacts from the colonial era.

Contemporary art galleries, however, appear to be absent from these discussions and actions. My research aims to tackle racism within English public contemporary art galleries. As part of it, I asked artists, curators and gallery workers to share their experiences with me for #GallerySoWhite, a digital exhibition highlighting people’s experiences of institutional racism in English contemporary art galleries. What I found was alarming.

Dismantling the white cube

If you asked someone living in the west to imagine the inside of a contemporary art gallery, most would picture a timeless, minimalist, white-walled, cube-shaped space with no historical context. The concept of “decolonisation” might not seem relevant at first.

However, if you look at the history of these white cube galleries, you will find that the overwhelming whiteness of these spaces – both in terms of the walls themselves and the people they are catered towards – is not something that has occurred by chance. Many of them rely on approaches that specifically elevate western art and culture above others.

Read more: From Africa to Peckham: how we decolonise culture by rehumanising people

Over the last few decades contemporary galleries have attempted to address cultural diversity issues through surface-level diversity and inclusion initiatives that focus on programming and optics. Projects like these have been around for decades, yet they have not helped to majorly improve the representation and treatment of people of colour.

Amplifying marginalised voices

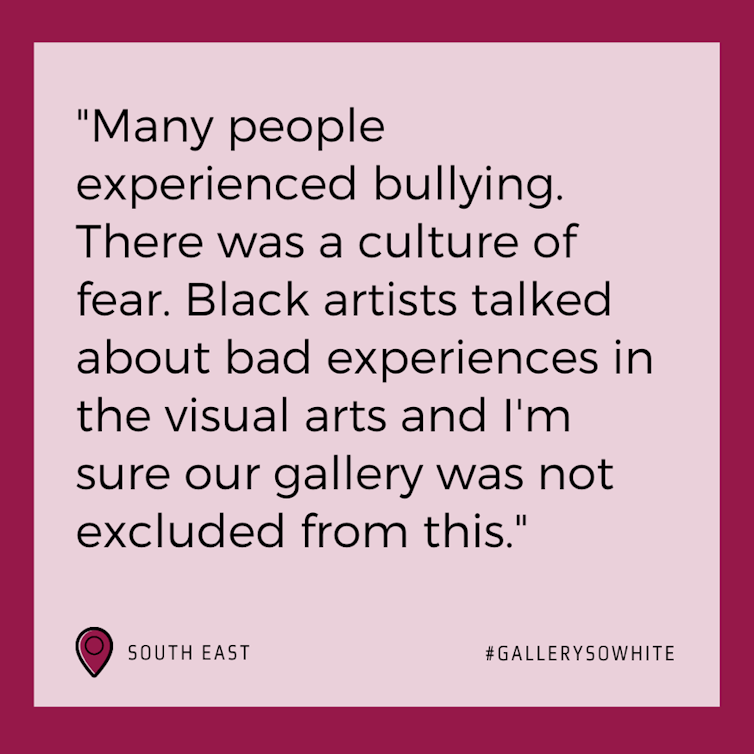

One anonymous testimony I received as part of my research, from a gallery employee in the south-east of England, shows how challenging it can be to work in these environments:

I tried to help create relationships with local communities and organisations from marginalised backgrounds, but the efforts were not welcomed by the director and it was all seen as secondary to the hobnobbing with the white rich potential benefactors, artists and arts sector.

Another anonymous submission from a person who worked in a London gallery reads:

Where interacting with galleries becomes exploitative is when you look at the number of Black and brown people on zero hours contracts or working freelance. From curators to gallery assistants, being Black in the art world means that you would have to come to terms with, and participate in, your own precarity. It is demoralising.

These are just a few of many testimonies I received that provide a glimpse into the hostile environments within many white cubes across the country. Participants completed an anonymous online survey where they were asked to share information about their experiences. It’s fascinating to see how many similar stories have been submitted. Overall, they show how urgently contemporary galleries need to confront the legacies of discrimination and racism.

The inspiration behind using social media to collect and present research came from observing how the art world responded to 2020 Black Lives Matter protests. In attempts to show their commitment to anti-racism, a number of galleries posted black squares and statements on social media.

Not long after, people took to social media to share examples of racism that they had experienced within these galleries. These online exchanges revealed how easily institutions can perform diversity while maintaining discrimination.

Social media plays an important role in providing platforms for marginalised communities, but working in the arts can be precarious. More people may be speaking up, yet going public about racism is not something that everyone can do without facing repercussions.

That’s why some people prefer to share through anonymous platforms like @changethemusuem, an Instagram account that shares insider stories about museums in the US. In a similar respect, #GallerySoWhite aims to give people who have worked in these spaces in England a chance to share their experiences with the world.

Public spaces like galleries shouldn’t simply provide for small, privileged pools of people. To tackle institutional racism, they need to look beyond tokenism and diversity projects and embrace conversations about decolonisation. Only once these issues have been addressed can we experience the kind of long-lasting change that the art sector needs.