In the Treasurer office they’ve been studying former budgets. They’ve concluded that Peter Costello’s first, in 1996, was the toughest – and the most popular.

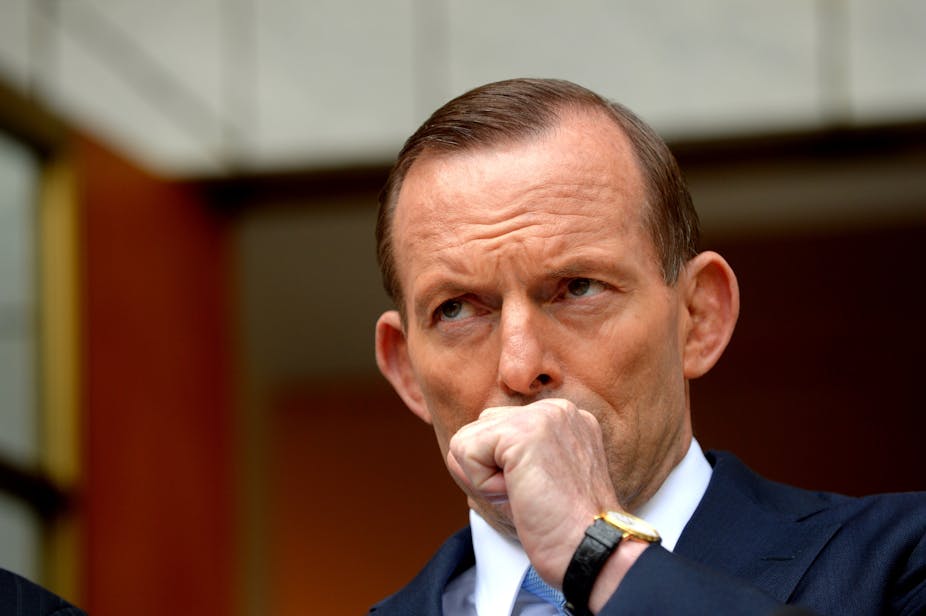

As the budget work reaches its peak, in the Prime Minister’s office they must have nightmares about Tony Abbott’s pre-election show-stopper line: “No cuts to education, no cuts to health, no change to pensions, no change to the GST and no cuts to the ABC or SBS”.

The GST pledge is safe (for the time being) but there will be arguments on the night of May 13 and later about the extent to which the other promises have been trashed, in letter or spirit.

Abbott, who campaigned relentlessly on Julia Gillard’s breaking of her “no carbon tax” commitment, is caught between what needs to be done to put the budget into shape in the quickest time and the political imperative of keeping his word to the voters.

The wisdom running around Canberra is that voters expect a tough budget and the government will be marked down if they don’t get one. Is this true? The circumstances may demand toughness, and the commentators will be censorious if it’s squibbed. But out in voter land, there will be an equal or greater danger if people feel betrayed by an untrustworthy government.

A misjudgement about where to pitch a budget can poison the political well. After Paul Keating clinched the “unwinnable election” of 1993, the budget that treasurer John Dawkins brought down that year was full of nasties. The political cost was enormous.

Paul Kelly in The March of Patriots goes so far as to say the Keating government’s death warrant was signed that day. The Dawkins budget “was an act of economic courage and a political death sentence”. It “extracted the toll for Keating’s pre-election promises,” and was later “battered by the caucus and then by the Senate,” with changes being made.

The relationship between Keating and Dawkins during that budget’s framing was fractious, and though Labor had just had an unexpected victory, it was an “old” government. This new government is a very different proposition. But the 1993 experience remains salutary for budget framers. Budget balances are delicate in more ways than those revolving around the bottom line. Messages must be carefully explained and justified; enough must be done to make a difference (especially in the first year of a new administration) but not so much that there’s change overload, and faith must be kept to the extent that the government doesn’t come to be seen as cynical and tricky.

The indications are the government wants to be ambitious on May 13, as Joe Hockey mounts his assault on the “age of entitlement”.

In particular, Hockey has been talking up the escalating cost of the pension system and the need for containment, especially of the age pension.

On the table are raising the pension age to 70 in the long term - three years older than the 67 in 2023 that is already in the system from the Labor government; reviewing the indexation arrangements to move to a less generous system (the pension is linked to male total average weekly earnings rather than the consumer price index) and looking at the income and assets qualifications for eligibility.

Quite how these measures could fit with Abbott’s “no change to pensions” is hard to see. Going to 70 might be less of a problem – although it is more dramatic – than, for example, fiddling with indexation. Any attempt to include the family house in the eligibility test would be fraught. Older people’s entitlements and family homes are two highly sensitive areas in politics; put them together, and only the bravest would go there.

Pressed on pensions this week, Abbott said: “If there is one lesson to be learned from the political quagmire that the former government got itself into, it is: keep your commitments. So we will keep them.

"But one of the most fundamental commitments of all was to get the budget back under control, to put the budget back on to a path to a sustainable surplus.”

This could be read as “promises are sacrosanct”, or “there is a hierarchy of promises which might mean some get compromised for others”. His words were interpreted both ways, according to the preferences of those reading the tea leaves.

Among other politically character-building measures, the government is leaning to introducing a Medicare co-payment. Cabinet’s expenditure review committee has yet to make a final decision and details are still being worked on. Around $5, it would yield significant savings over the medium term. But it has been opposed by the Australian Medical Association, so would be another hard selling job.

As one government person said: “No one is looking for good news stories out of this budget”.

Hockey’s first budget will be delivered to an electorate that is still disillusioned with politics, somewhat sullen and suspicious, and not much enamoured of the administration it elected. The budget needs to be an identity stamp for the government, seen as doing the economic job but doing it fairly, delivering responsible reform rather than going on an ideological mission, keeping trust. If it fails these tests, the atmosphere will sour further and the government will have an uphill battle in its next efforts to deliver change.

Listen to John Hewson on the Politics with Michelle Grattan podcast, here.