During a Nov. 22 celebration of Donald Trump’s election triumph, members of a far-right organization, the National Policy Institute, were filmed extending a stiff arm in the iconic “Heil Hitler” salute of Nazi Germany. Ensuring there would be no mistaking the gesture, National Policy Institute President Richard Spencer shouted, “Hail Trump, hail our people, hail victory!”

The video echoed, on a very small scale, mass rallies that were once held in Nazi Germany. Huge crowds with their arms raised “were an essential part of Nazi propaganda, designed to demonstrate public solidarity with the policies of the Nazi Party,” write Garth S. Jowett and Victoria O’Donnell in “Propaganda & Persuasion.”

Two years ago, when I prepared slides on the Nazi salute for my rhetoric class on “The Art of Argument,” I had no idea that I would soon see that gesture reborn in the America political landscape.

Before the Nov. 8 election, the use of the Nazi salute by a fringe group might have been dismissed as a “Springtime for Hitler” moment, something too outrageous to be taken seriously, as satirized in “The Producers” movie and Tony-winning Broadway musical.

Post-election, the gesture represents something that demands serious attention. Historically, hand and arm gestures have had as powerful an impact as slogans or symbols. That Nazi salute should be considered in that context.

History of gestures

Certain gestures can send powerful rhetoric and cultural messages. There’s even an International Society for Gesture Studies which promotes gesture studies worldwide.

Consider a common two-finger salute. During World War II, the two-finger salute of “V for Victory” gave courage to Allied troops. A similar gesture morphed into the peace sign, a gesture of resistance and solidarity during the 1960s protests against the Vietnam War. Turn the V-sign palm facing in, and you have a gesture that is considered rude in the United Kingdom.

The Vulcan salute, adopted by actor Leonard Nimoy for the original “Star Trek” series, came from a Jewish blessing, and has become part of the American lexicon of gesture. After Nimoy’s death, NASA astronaut Terry Virts made the “Live Long and Prosper” sign while aboard the International Space Station and sent it to Earth via Twitter.

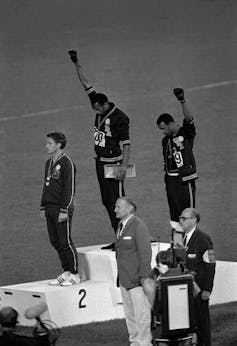

The current uproar over athletes kneeling during the National Anthem pales beside the outrage that greeted athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos when they each held aloft a black-gloved fist clenched in the “Black Power” salute during their medal ceremony at the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City.

A three-fingered salute plays a key role in the book series “The Hunger Games.” According to narrator Katniss Everdeen, raising a hand with three fingers extended is “an old and rarely used gesture [that] means thanks, it means admiration, it means good-bye to someone you love.” In the book, the gesture becomes a sign of resistance.

Fiction became reality in May 2014, when three Thailand political activists protesting a coup held their hands up in a three-finger salute and were detained. Thai authorities likely never heard of Katniss Everdeen, yet they knew a sign of rebellion when they saw it.

As old as politics

“Gestures are as old as politics itself,” writes Nathaniel Zelinsky in a Foreign Affairs article that probes the use of gestures employed by radical Islamists and other groups in Middle East. Zelinsky argues that we must pay attention to these hand signals as they “communicate complex political messages that Western observers have largely ignored.”

Gestures, he notes, including the Nazi salute, became especially important with the advent of mass media in the 20th century:

“Consider what is perhaps the best-known example: Adolf Hitler’s fascist salute. In a single gesture, Hitler communicated the power of National Socialism, the obedience of German crowds, and his own role as a supreme leader. And because pictures of him saluting were printed in newspapers around the world, the symbol reached billions.”

In Europe, the Nazi salute is so potent it can be considered hate speech. To get around these laws, a controversial French comedian created an inverted Nazi salute called the “quenelle,” in which a stiff arm is held down, rather than up, and is interpreted as support of anti-Zionism. The gesture has spread across the internet through selfies, as Gavriel Rosenfeld explores in his book “Hi Hitler: How the Nazi Past Is Normalized in Contemporary Culture.”

Unlike in France, gestures may fall under First Amendment protection in the United States, affording protection to even Nazi salutes. The National Policy Institute may have taken advantage of this protection in that November meeting. Whether deliberate or not, Trump supporters have displayed a Heil Hitler-like gesture at more than one Trump rally.

The stiff-arm salute is not a trivial gesture. It is not alt-right so much as it is Third Reich redux, a revival of a dangerous ideology. Just consider the message from the National Policy Institute’s website, which declares it is “dedicated to the heritage, identity, and future of people of European descent in the United States, and around the world.” It is not a stretch to compare this to the Nazi veneration of the supposed “Aryan” or “ethnically pure” race.

Thus far, the president-elect has expressed more outrage over the cast of “Hamilton” addressing Mike Pence at the theater than neo-Nazis saluting in his name.