A new global “soft power” ranking recently reported that the democratic states of North America and Western Europe were the most successful at achieving their diplomatic objectives “through attraction and persuasion”.

Countries such as the US, the UK, Germany and Canada, the report claimed, are able to promote their influence through language, education, culture and the media, rather than having to rely on traditional forms of military or diplomatic “hard power”.

The notion of soft power has also returned to prominence in Britain since the Brexit vote, with competing claims that leaving Europe will either damage Britain’s reputation abroad or increase the importance of soft power to British diplomacy.

Although the term “soft power” was popularised by the political scientist Joseph Nye in the 1980s, the practice of states attempting to exert influence through their values and culture goes back much further. Despite what the current soft power list would suggest, it has never been solely the preserve of liberal or democratic states. The Soviet Union, for example, went to great efforts to promote its image to intellectuals and elites abroad through organisations such as VOKS (All-Union Society for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries).

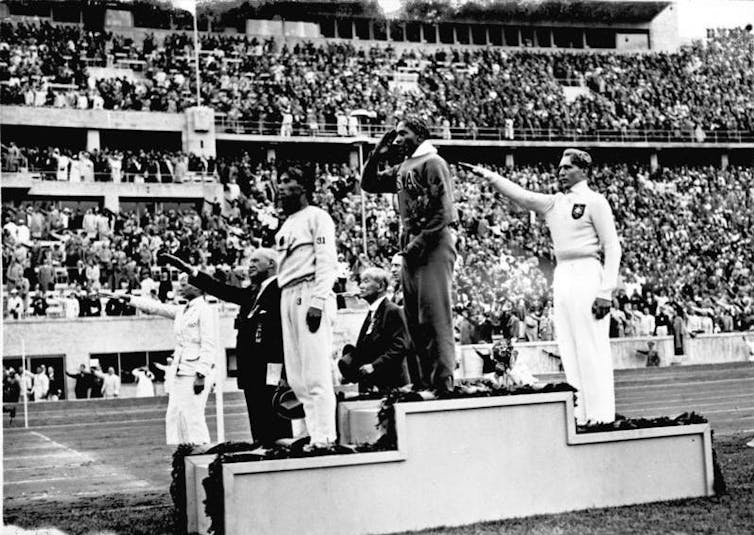

Perhaps more surprisingly, right-wing authoritarian and fascist states also used soft power strategies to spread their power and influence abroad during the first half of the 20th century. Alongside their aggressive and expansionist foreign policies, Hitler’s Germany, Mussolini’s Italy and other authoritarian states used the arts, science, and culture to further their diplomatic goals.

‘New Europe’

Prior to World War II, these efforts were primarily focused on strengthening ties between the fascist powers. The 1930s, for example, witnessed intensive cultural exchanges between fascist Italy and Nazi Germany. Although these efforts were shaped by the ideology of their respective regimes, they also built on pre-fascist traditions of cultural diplomacy. In the aftermath of World War I, Weimar Germany had become adept at promoting its influence through cultural exchanges in order to counter its diplomatic isolation. After 1933, the Nazi regime was able to shape Weimar-era cultural organisations and relationships to its own purpose.

This authoritarian cultural diplomacy reached its peak during World War II, when Nazi Germany attempted to apply a veneer of legitimacy to its military conquests by promoting the idea of a “New Europe” or “New European Order”. Although Hitler was personally sceptical about such efforts, Joseph Goebbels and others within the Nazi regime saw the “New Europe” as a way to gain support. Nazi propaganda promoted the idea of “European civilization” united against the threat of “Asiatic bolshevism” posed by the Soviet Union and its allies.

Given the lack of genuine political cooperation within Nazi-occupied Europe, these efforts relied heavily on cultural exchange. The period from the Axis invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941 until the latter stages of 1943 witnessed an explosion of “European” and “international” events organised under Nazi auspices. They brought together right-wing elites from across the continent – from women’s groups, social policy experts and scientists to singers, dancers and fashion designers.

All of these initiatives, however, faced a common set of problems. Chief among them was the challenge of formulating a model of international cultural collaboration which was distinct from the kind of pre-war liberal internationalism which the fascist states had so violently rejected. The Nazi-dominated European Writers’ Union, for example, attempted to promote a vision of “völkisch” European literature rooted in national, agrarian cultures which it contrasted to the modernist cosmopolitanism of its Parisian-led liberal predecessors. But as a result, complained one Italian participant, the union’s events became “a little world of the literary village, of country poets and provincial writers, a fair for the benefit of obscure men, or a festival of the ‘unknown writer’”.

Deutschland über alles

Despite the language of European cooperation and solidarity which surrounded these organisations, they were ultimately based on Nazi military supremacy. The Nazis’ hierarchical view of European races and cultures prompted resentment even among their closest foreign allies.

These tensions, combined with the practical constraints on wartime travel and the rapid deterioration of Axis military fortunes from 1943 onwards, meant that most of these new organisations were both ineffective and short-lived. But for a brief period they succeeded in bringing together a surprisingly wide range of individuals committed to the idea of a new, authoritarian era of European unity.

Echoes of the cultural “New Europe” lived on after 1945. The Franco regime, for example, relied on cultural diplomacy to overcome the international isolation it faced. The Women’s section of the Spanish fascist party, the Falange, organised “choir and dance” groups which toured the world during the 1940s and 1950s, travelling from Wales to West Africa to promote an unthreatening image of Franco’s Spain through regional folk dances and songs.

But the far-right’s golden age of authoritarian soft power ended with the defeat of the Axis powers. The appeal of fascist culture was fundamentally undermined by post-war revelations about Nazi genocide, death camps and war crimes. At the other end of the political spectrum, continued Soviet efforts to attract support from abroad were hampered by the invasion of Hungary in 1956 and the crushing of the Prague Spring in 1968.

This does not mean that authoritarian soft power has been consigned to history. Both Russia and China made the top 30 of the most recent global ranking, with Russia in particular leading the way in promoting its agenda abroad through both mainstream and social media.

The new wave of populist movements sweeping Europe and the United States often also put the promotion of national cultures at the core of their programmes. France’s Front National, for example, advocates the increased promotion of the French language abroad on the grounds that “language and power go hand-in-hand”. We may well see the emergence of authoritarian soft power re-imagined in the 21st century.